Margaret Sanger

Sanger worked as a nurse in the slums of New York City, where she often treated mothers desperate to avoid conceiving additional children, some of whom were suffering the effects of unsanitary back-alley abortions.

[7] Supported by her two older sisters, Margaret Higgins attended the Hudson River Institute at Claverack College, before enrolling in 1900 at White Plains Hospital as a student nurse.

[14] The hardships women faced were epitomized in a story that Sanger would recount in her speeches: while she was working as a nurse, she was called to the apartment of a woman, "Sadie Sachs", who had a severe sepsis infection due to a self-induced abortion.

Sanger would sometimes end the story by saying, "I threw my nursing bag in the corner and announced ... that I would never take another case until I had made it possible for working women in America to have the knowledge to control birth".

[17] Sanger opposed abortion, not on theological grounds, but as a societal ill and public health danger – which would disappear, she believed, if women were able to prevent unwanted pregnancy.

[23] Sanger's political interests, her emerging feminism and her nursing experience led her to believe that only by liberating women from the risk of unwanted pregnancy would fundamental social change take place.

[44][45] Under his tutelage, she expanded her birth control strategy to incorporate the additional benefit of stress-free, enjoyable sex; and came to adopt his view of sexuality as a powerful, liberating force.

[55] On October 16, 1916, Sanger opened a family planning and birth control clinic – the first in the United States – in the Brownsville neighborhood of the Brooklyn borough of New York.

[65][66][j] The publicity surrounding Sanger's arrest, trial and appeal sparked birth control activism across the United States and earned the support of numerous donors, who would provide her with funding for future endeavors.

[73] Sanger believed that these efforts to limit family size were a manifestation of women's desire for freedom, writing: "A free race cannot be born of slave mothers.

[76] After World War I, Sanger continued to be frustrated by the inverted priorities of charities: they provided free obstetric and post-birth care to indigent women, yet failed to offer birth control or assistance in raising the children.

[78] Support from wealthy donors in the early 1920s enabled Sanger to expand her reach beyond local, small-scale activism, and allowed her to organize the American Birth Control League (ABCL).

[79] The founding principles of the ABCL were: "We hold that children should be (1) Conceived in love; (2) Born of the mother's conscious desire; (3) And only begotten under conditions which render possible the heritage of health.

[81][82] The CRB was the first birth control clinic in the U.S. that could dispense contraceptives directly to patients; and its staff of doctors, nurses and social workers was entirely female.

[93] In 1925, Sanger's second husband, Noah Slee, contributed to the birth control movement by smuggling diaphragms into New York from Canada, hidden inside his company's cargo.

[101] Throughout the 1920s, Sanger and the ABCL expanded outward from their New York base by creating a network of birth control clinics across the country: Chicago (1924), Los Angeles (1925), San Antonio (1926), Detroit and Baltimore (1927), Cleveland, Newark, and Denver (1928), and Atlanta, Cincinnati, and Oakland (1929).

In 1929, James H. Hubert, an African American social worker and the leader of New York's Urban League, asked Sanger to open a clinic in Harlem.

"[116]When academic Angela Davis analyzed that quote, she interpreted the passage "We do not want word to go out" as evidence that Sanger led a secretive effort to reduce the African American population against its will.

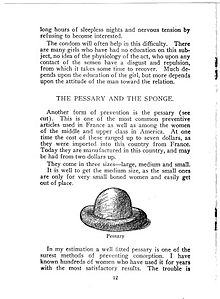

[123][125] The diaphragms were confiscated by the U.S. government, and Sanger's subsequent legal challenge of the Comstock laws led to a breakthrough 1936 court decision – United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries – which permitted physicians to dispense contraceptives nationwide.

[133] In the early 1950s, Sanger persuaded philanthropist Katharine McCormick to provide funding for biologist Gregory Pincus to develop the first birth control pill, which was eventually sold under the name Enovid.

[138] The Japanese government invited Sanger to Tokyo in 1954 to address the National Diet – she was the first foreigner to do so – where she gave a speech on "Population Problems and Family Planning".

[139][140] In the late 1930s, Sanger began spending the winters in Tucson, Arizona, intending to play a less critical role in the birth control movement.

In her view, contraception was beneficial for many reasons: It was safe, simple, inexpensive, reduced the number of unwanted pregnancies, addressed overpopulation, and – most importantly – it eliminated the need for dangerous abortions.

[170] Inspired by fellow free speech advocates, in 1914 she published The Woman Rebel with the express goal of triggering a legal challenge to the Comstock anti-obscenity laws banning dissemination of information about contraception.

[173][174] Sanger turned some of the boycotted speaking events to her advantage by inviting the press, and the resultant news coverage often generated public sympathy for her cause.

In response she stood on stage, silent, with a gag over her mouth, while her speech was read by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr.[177][178] Over the course of her career, Sanger was arrested several times for speaking or publishing prohibited information.

[180][181][182] Eugenic beliefs in the early 1900s covered a wide spectrum: at one extreme were those who overtly claimed the white race was superior, and wanted to reduce the population of certain other ethnicities.

[220][224][aa][ab] Sanger's eugenic proposals did not target specific ethnicities: instead, her goal was to improve the entire human race by reducing the reproduction of those who were considered unfit.

[274][194][229][275][aj] Another persistent falsehood is that Sanger applied her birth control polices with the intention of suppressing ethnic minorities – particularly the African American community.

[283][ah] Essayist Katha Pollitt and Sanger biographer Ellen Chesner criticized Planned Parenthood for succumbing to pressure from the anti-abortion movement.