Treaty of Tordesillas

That line of demarcation was about halfway between Cape Verde (already Portuguese) and the islands visited by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León), named in the treaty as Cipangu and Antillia (Cuba and Hispaniola).

[6] The Treaty of Tordesillas was intended to solve the dispute that arose following the return of Christopher Columbus and his crew, who had sailed under the Crown of Castile.

After learning of the Castilian-sponsored voyage, the Portuguese King sent a threatening letter to the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, stating that by the Treaty of Alcáçovas signed in 1479 and by the 1481 papal bull Aeterni regis that granted all lands south of the Canary Islands to Portugal, all of the lands discovered by Columbus belonged, in fact, to Portugal.

The Portuguese king also stated that he was already making arrangements for a fleet (an armada led by Francisco de Almeida) to depart shortly and take possession of the new lands.

[7] The Spanish rulers replied that Spain owned the islands discovered by Columbus and warned King John II not to permit anyone from Portugal to go there.

Finally, the rulers invited Portugal to send ambassadors to begin diplomatic negotiations aimed at settling the rights of each nation in the Atlantic.

[7] On 4 May 1493, Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia), an Aragonese from Valencia by birth, decreed in the bull Inter caetera that all lands west of a pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west of any of the islands of the Azores or the Cape Verde Islands should belong to Castile, although territory under Christian rule as of Christmas 1492 would remain untouched.

Another bull, Dudum siquidem, entitled Extension of the Apostolic Grant and Donation of the Indies and dated 25 September 1493, gave all mainlands and islands, "at one time or even still belonging to India" to Spain, even if east of the line.

[citation needed] The Portuguese King John II was not pleased with that arrangement, feeling that it gave him far too little land—it prevented him from possessing India, his near-term goal.

As one scholar assessed the results, "both sides must have known that so vague a boundary could not be accurately fixed, and each thought that the other was deceived", concluding that it was a "diplomatic triumph for Portugal, confirming to the Portuguese not only the true route to India, but most of the South Atlantic".

The easternmost part of current Brazil was granted to Portugal when in 1500 Pedro Álvares Cabral landed there while he was en route to India.

[11] One scholar points to Cabral's landing on the Brazilian coast 12 degrees farther south than the expected Cape São Roque, such that "the likelihood of making such a landfall as a result of freak weather or a navigational error was remote; and it is highly probable that Cabral had been instructed to investigate a coast whose existence was not merely suspected, but already known".

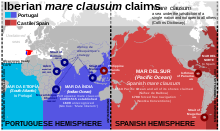

[23] But Portugal's discovery of the highly valued Moluccas in 1512 caused Spain to argue in 1518[citation needed] that the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the earth into two equal hemispheres.

The Treaty of Vitoria, negotiated between Spain and Portugal on 19 February 1524, called for the Junta of Badajoz to meet in an attempt to reach an agreement on the anti-meridian, which ultimately failed.

[citation needed] Portugal gained control of all lands and seas west of the Zaragoza line, including all of Asia and its neighboring islands so far discovered, leaving Spain most of the Pacific Ocean.

Although a number of expeditions sent from New Spain arrived in the Philippines, they were unable to establish a settlement because the return route across the Pacific was unknown.