Tunneling nanotube

[2][3][4] Tunneling nanotubes that are less than 0.7 micrometers in diameter, have an actin structure and carry portions of plasma membrane between cells in both directions.

Larger TNTs (>0.7 μm) contain an actin structure with microtubules and/or intermediate filaments, and can carry components such as vesicles and organelles between cells, including whole mitochondria.

Closed ended TNTs do not have continuous cytoplasm as there is a gap junction cap that only allows small molecules and ions to flow between cells.

[9] These structures have shown involvement in cell-to-cell communication, transfer of nucleic acids such as mRNA and miRNA between cells in culture or in a tissue, and the spread of pathogens or toxins such as HIV and prions.

[7] Since these publications, more TNT-like structures have been recorded, containing varying levels of F-actin, microtubules and other components, but remaining relatively homogenous in terms of composition.

[3][19] Some dendritic cells and THP-1 monocytes have been shown to connect via tunneling nanotubes and display evidence of calcium flux when exposed to bacterial or mechanical stimuli.

The TNTs demonstrated in this study propagated at initial speed of 35 micrometers/second and have shown to connect THP-1 monocytes with nanotubes up to 100 micrometers long.

[3] p53 activation has also been implicated as a necessary mechanism for the development of TNTs, as the downstream genes up-regulated by p53 (namely EGFR, Akt, PI3K, and mTOR) were found to be involved in nanotube formation following hydrogen peroxide treatment and serum starvation.

TNT-like structures called streamers, which are extremely thin protrusions, did not form when cultured with cytochalasin D, an F-actin depolymerizing compound.

[36] In one study, Ahmad et al. used four lines of mesenchymal stem cells, each expressing either a differing phenotype of the Rho-GTPase Miro1; a higher level of Miro1 was associated with more efficient mitochondrial transfer via TNTs.

[25] Several studies have shown, through the selective blockage of TNT formation, that TNTs are a primary mechanism for the trafficking of whole mitochondria between heterogeneous cells.

[40] Researchers have found that "Long-term nonprogressors" of HIV, who can control the virus without antiretroviral therapy, have a defect in their dendritic cells' ability to create TNTs.

Future applications look to either inhibit TNTs to prevent nanomedicine toxicity from reaching neighboring cells, or to promote TNT formation to increase positive effects of the medicine.

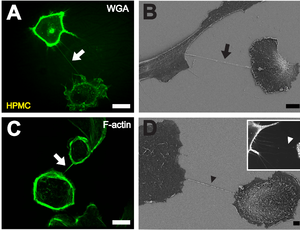

B Depiction of a TNT (black arrow) between two cells with scanning electron microscopy. Scale bar: 10 μm.

C Fluorescently labeled F-actin (white arrow) present in TNTs between individual HPMCs. Scale bar: 20 μm.

D Scanning electron microscope image of a potential TNT precursor (black arrowhead). Insert shows a fluorescence microscopic image of filopodia-like protrusions (white arrowhead) approaching a neighboring cell. Scale bar: 2 μm. [ 1 ]