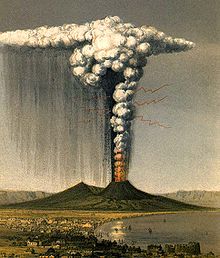

Volcanology

Volcanology (also spelled vulcanology) is the study of volcanoes, lava, magma and related geological, geophysical and geochemical phenomena (volcanism).

Many other developments in fluid dynamics, experimental physics and chemistry, techniques of mathematical modelling, instrumentation and in other sciences have been applied to volcanology since 1841.

[3] Surface deformation monitoring includes the use of geodetic techniques such as leveling, tilt, strain, angle and distance measurements through tiltmeters, total stations and EDMs.

Gas emissions may be monitored with equipment including portable ultra-violet spectrometers (COSPEC, now superseded by the miniDOAS), which analyzes the presence of volcanic gases such as sulfur dioxide; or by infra-red spectroscopy (FTIR).

[12] Some of the techniques mentioned above, combined with modelling, have proved useful and successful in the forecasting of some eruptions,[13]: 1–2 such as the evacuation of the locality around Mount Pinatubo in 1991 that may have saved 20,000 lives.

The earliest known recording of a volcanic eruption may be on a wall painting dated to about 7,000 BCE found at the Neolithic site at Çatal Höyük in Anatolia, Turkey.

The Roman poet Virgil, in interpreting the Greek mythos, held that the giant Enceladus was buried beneath Etna by the goddess Athena as punishment for rebellion against the gods; the mountain's rumblings were his tormented cries, the flames his breath and the tremors his railing against the bars of his prison.

[19] Lucretius, a Roman philosopher, claimed Etna was completely hollow and the fires of the underground driven by a fierce wind circulating near sea level.

His nephew, Pliny the Younger, gave detailed descriptions of the eruption in which his uncle died, attributing his death to the effects of toxic gases.

Thirteenth century Dominican scholar Restoro d'Arezzo devoted two entire chapters (11.6.4.6 and 11.6.4.7) of his seminal treatise La composizione del mondo colle sue cascioni to the origin of the endogenous energy of the Earth.

[20] During the Renaissance, observers as Bernard Palissy, Conrad Gessner, and Johannes Kentmann (1518–1568) showed a deep intense interest in the nature, behavior, origin and history of the terrestrial globe.

The volcanoes of southern Italy attracted naturalists ever since the Renaissance led to the rediscovery of Classical descriptions of them by wtiters like Lucretius and Strabo.

[23] The Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) witnessed eruptions of Mount Etna and Stromboli, then visited the crater of Vesuvius and published his view of an Earth with a central fire connected to numerous others caused by the burning of sulfur, bitumen and coal.

Volcanic eruptions and earthquakes were generally linked in these systems to the existence of great open caverns under the Earth where inflammable vapours could accumulate until they were ignited.

In William Whiston's theory the presence of underground air was necessary if ignition were to take place, while John Woodward stressed that water was essential.

A number of writers, most notably Thomas Robinson, believed that the Earth was an animal, and that its internal heat, earthquakes and eruptions were all signs of life.

The register of these processions and the 1779 and 1794 diary of Father Antonio Piaggio allowed British diplomat and amateur naturalist Sir William Hamilton to provide a detailed chronology and description of Vesuvius' eruptions.