War guilt question

Structured in several phases, and largely determined by the impact of the Treaty of Versailles and the attitude of the victorious Allies, this debate also took place in other countries involved in the conflict, such as in the French Third Republic and the United Kingdom.

The war guilt debate motivated historians such as Hans Delbrück, Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Gerhard Hirschfeld, and Fritz Fischer, but also a much wider circle including intellectuals such as Kurt Tucholsky and Siegfried Jacobsohn, as well as the general public.

After four years of war on multiple fronts in Europe and around the world, an Allied offensive began in August 1918, and the position of Germany and the Central Powers deteriorated, leading them to sue for peace.

The signatures by Hermann Müller and Johannes Bell, who had come to office through the Weimar National Assembly in 1919, fed the stab-in-the-back myth propagated primarily by Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff and later by Adolf Hitler.

Two additional units were created in April 1921, in an effort to appear to be independent of the ministry: the Center for the Study of the Causes of the War (Zentralstelle zur Erforschung der Kriegsursachen), and the Working Committee of German Associations Arbeitsausschuss.

[33][better source needed] At the first pacifist congress in June 1919, when a minority led by Ludwig Quidde repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, the German League for Human Rights and the Center for International Law [fr] made the question of responsibility a central theme.

This led to the reunification of a minority of the party with the Social Democrats in 1924 and the inclusion of some pacifist demands in the 1925 Heidelberg Program [de; fr][citation needed] Walter Fabian, journalist and social-democratic politician, published Die Kriegsschuldfrage in 1925.

Even if the emperor and chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg tried to defuse events at the last moment, the army threw its full weight into the effort in order to force the situation.

Chief of Staff von Moltke sent a telegram in which he stated that Germany would mobilize, but William II asserted that there was no longer any reason to declare war since Serbia accepted the ultimatum.

[52] This legend weakened the Social Democratic Party through slander campaigns based on various allegations: namely, that the SDP not only betrayed the army and Germany by signing the armistice, but also repressed the Spartacist uprising, proclaimed the republic, and refused (for some of its members) to vote for war credits in 1914.

"[t][56] The Working Committee of German Associations gave its support to Adolf Hitler as early as 1936,[57] in particular through its president, Heinrich Schnee, for whom the "rescue of the fatherland" required "the joint action of all parties on national soil, including the NSDAP".

[aa] Alfred von Wegerer quoted Hitler's statement in the Berliner Monatshefte in December 1934 and linked it to the expectation that at last the "honor of the nation", which had been "most grievously violated" by the Treaty of Versailles, would be "fully restored".

Julius Hashagen wrote retrospectively about the Berliner Monatshefte in 1934: "... under the masterful and meritorious leadership of the journal and its staff," German war guilt research had made "considerable progress".

William G. S. Adams, who saw the war as a "struggle of liberty against militarism," tried to prove that Germany had deliberately risked a "European conflagration" in order to force England to honor its "moral obligations" to France and Belgium.

[…] Thus in both cases the supposedly counterproductive and dangerous foreign policies of Germany and Austria-Hungary culminating in their gamble in 1914 are linked to a wider problem and at least partly explained by it: the failure or refusal of their regimes to reform and modernize in order to meet their internal political and social problems.Australian historian Christopher Clark also disagreed in his 2012 study The Sleepwalkers.

Soviet historian Igor Bestushev disputed the attempt at national exoneration and stated in opposition to Fritz Fischer:[105] The examination of the facts shows, on the contrary, that the policy of all the Great Powers, including Russia, objectively led to the World War.

In 1976 Reinhold Zilch criticized the "clearly aggressive aims of Reichsbank President Rudolf Havenstein on the eve of war",[106] while in 1991 Willibald Gutsche argued that in 1914, "in addition to the coal and steel monopolists, [...] influential representatives of the big banks and electrical and shipping monopolies were also not inclined towards peace".

[109] For Emperor Franz Joseph I, the responsibilities for military action against Serbia were clear at the end of July 1914: "The machinations of a hateful adversary compel Me, in order to preserve the honor of My Monarchy and to protect its position of power ... to take up the sword.

In his three-volume critical work, published in 1942-1943 (Le origini della guerra del 1914), Albertini comes to the conclusion that all European governments had a share of responsibility in the outbreak of the war, while pointing to German pressure on Austria-Hungary as the decisive factor in the latter's bellicose behaviour in Serbia.

[121] Hans Herzfeld's [de] response in Historischen Zeitschrift (Historical Journal) marked the beginning of a controversy that lasted until about 1985 and permanently changed the national conservative consensus on the question of war guilt.

[123] Given that Germany wanted, desired and covered up the Austrian-Serbian war and, trusting in German military superiority, deliberately chose to enter into conflict with Russia and France in 1914, the German Imperial leadership bears a considerable part of the historical responsibility for the outbreak of a general war.Initially, right-wing conservative authors such as Giselher Wirsing accused Fischer of pseudo-history and, like Erwin Hölzle [de], tried to uphold the Supreme Army Command's hypothesis of Russian war guilt.

[130] Wolfgang Steglich, on the other hand, used foreign archival material to emphasize German-Austrian efforts to achieve an amicable or separate peace since 1915,[131] and lack of crisis management by Germany's opponents.

[136] More recent publications by and large stick to the earlier view, namely that Germany contributed significantly to the fact "that as the crisis widened, alternative strategies for de-escalation did not bear fruit ...

[137] In contrast to Christopher Clark's view, Gerd Krumeich, John C. G. Röhl, and Annika Mombauer summed up the situation as[clarify] the Central Powers bearing primary responsibility for the outbreak of the war, even if it could not be blamed on them alone.

Today, it relates primarily to the following topics: Anne Lipp's Meinungslenkung im Krieg [141] (Shaping Opinion in War) analyzed how soldiers, military leaders, and wartime propaganda reacted to the front-line experience of mass destruction.

"Fatherland Instruction" [de][ak] offered front-line soldiers heroic images for identification, in order to redirect their horror, and their fears of death and defeat into the opposite of what they had experienced.

[142] In 2002, the historians Friedrich Kiessling [de] and Holger Afflerbach [fr; pl] emphasized the opportunities for détente between the major European powers that had existed until the assassination in Sarajevo which had not been exploited.

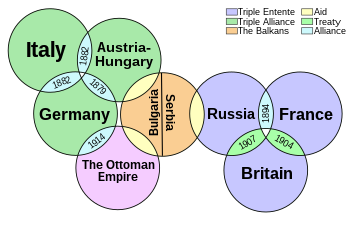

Other historians disagreed: in 2003, Volker Berghahn argued that the structural causes of the war, which went beyond individual government decisions, could be found in the alliance system of the European great powers and their gradual formation of blocs.

Like Fischer and others, he too saw the naval arms race and competition in the conquest of colonies as major factors by which all of Europe's great powers contributed to the outbreak of war, albeit with differences in degree.

The decision makers had shown a high willingness to take risks and at the same time had aggravated the crisis with mismanagement and miscalculations, until the only solution seemed to them to be the "flight forward"[al] into war with the other great powers.