Torah

[21][22] Scholars usually refer to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible as the 'Pentateuch' (/ˈpɛn.təˌtjuːk/, PEN-tə-tewk; Ancient Greek: πεντάτευχος, pentáteukhos, 'five scrolls'), a term first used in the Hellenistic Judaism of Alexandria.

[28] At God's command Noah's descendant Abraham journeys from his home into the God-given land of Canaan, where he dwells as a sojourner, as does his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob.

The book tells how the ancient Israelites leave slavery in Egypt through the strength of Yahweh, the God who has chosen Israel as his people.

[33] The book has a long and complex history, but its final form is probably due to a Priestly redaction (i.e., editing) of a Yahwistic source made some time in the early Persian period (5th century BCE).

[35] Numbers is the culmination of the story of Israel's exodus from oppression in Egypt and their journey to take possession of the land God promised their fathers.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to the Israelites by Moses on the plains of Moab, shortly before they enter the Promised Land.

Presented as the words of Moses delivered before the conquest of Canaan, a broad consensus of modern scholars see its origin in traditions from Israel (the northern kingdom) brought south to the Kingdom of Judah in the wake of the Assyrian conquest of Aram (8th century BCE) and then adapted to a program of nationalist reform in the time of Josiah (late 7th century BCE), with the final form of the modern book emerging in the milieu of the return from the Babylonian captivity during the late 6th century BCE.

[48]By contrast, the modern scholarly consensus rejects Mosaic authorship, and affirms that the Torah has multiple authors and that its composition took place over centuries.

[49] The groundwork was laid with the investigation of the origins of the written sources in oral compositions, implying that the creators of J and E were collectors and editors and not authors and historians.

[50] Rolf Rendtorff, building on this insight, argued that the basis of the Pentateuch lay in short, independent narratives, gradually formed into larger units and brought together in two editorial phases, the first Deuteronomic, the second Priestly.

[51] By contrast, John Van Seters advocates a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah was derived from a series of direct additions to an existing corpus of work.

[54] The majority of scholars today continue to recognize Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.

[64] Frei's theory was, according to Eskenazi, "systematically dismantled" at an interdisciplinary symposium held in 2000, but the relationship between the Persian authorities and Jerusalem remains a crucial question.

[68] In his seminal Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels, Julius Wellhausen argued that Judaism as a religion based on widespread observance of the Torah and its laws first emerged in 444 BCE when, according to the biblical account provided in the Book of Nehemiah (chapter 8), a priestly scribe named Ezra read a copy of the Mosaic Torah before the populace of Judea assembled in a central Jerusalem square.

[clarify][citation needed] More recently, Yonatan Adler has argued that in fact there is no surviving evidence to support the notion that the Torah was widely known, regarded as authoritative, and put into practice prior to the middle of the 2nd century BCE.

[71] Adler explored the likelihhood that Judaism, as the widespread practice of Torah law by Jewish society at large, first emerged in Judea during the reign of the Hasmonean dynasty, centuries after the putative time of Ezra.

[73] Rabbinic writings state that the Oral Torah was given to Moses at Mount Sinai, which, according to the tradition of Orthodox Judaism, occurred in 1312 BCE.

Regular public reading of the Torah was introduced by Ezra the Scribe after the return of the Jewish people from the Babylonian captivity (c. 537 BCE), as described in the Book of Nehemiah.

[78] In the modern era, adherents of Orthodox Judaism practice Torah-reading according to a set procedure they believe has remained unchanged in the two thousand years since the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (70 CE).

Jews observe an annual holiday, Simchat Torah, to celebrate the completion and new start of the year's cycle of readings.

Orthodox and Conservative branches of Judaism accept these texts as the basis for all subsequent halakha and codes of Jewish law, which are held to be normative.

In a similar vein, Rabbi Akiva (c. 50 – c. 135 CE), is said to have learned a new law from every et (את) in the Torah (Talmud, tractate Pesachim 22b); the particle et is meaningless by itself, and serves only to mark the direct object.

In other words, the Orthodox belief is that even apparently contextual text such as "And God spoke unto Moses saying ..." is no less holy and sacred than the actual statement.

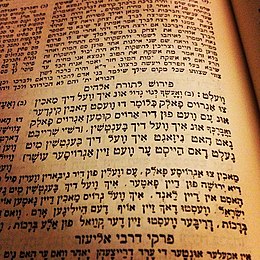

The fidelity of the Hebrew text of the Tanakh, and the Torah in particular, is considered paramount, down to the last letter: translations or transcriptions are frowned upon for formal service use, and transcribing is done with painstaking care.

Written entirely in Hebrew, a sefer Torah contains 304,805 letters, all of which must be duplicated precisely by a trained sofer ("scribe"), an effort that may take as long as approximately one and a half years.

Most modern Sifrei Torah are written with forty-two lines of text per column (Yemenite Jews use fifty), and very strict rules about the position and appearance of the Hebrew letters are observed.

The official recognition of a written Targum and the final redaction of its text, however, belong to the post-Talmudic period, thus not earlier than the fifth century C.E.

[93] The Torah has been translated by Jewish scholars into most of the major European languages, including English, German, Russian, French, Spanish and others.

The Islamic methodology of tafsir al-Qur'an bi-l-Kitab (Arabic: تفسير القرآن بالكتاب) refers to interpreting the Qur'an with/through the Bible.

[100] This approach adopts canonical Arabic versions of the Bible, including the Torah, both to illuminate and to add exegetical depth to the reading of the Qur'an.