Directionality (molecular biology)

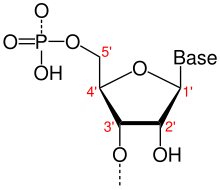

Directionality, in molecular biology and biochemistry, is the end-to-end chemical orientation of a single strand of nucleic acid.

In a DNA double helix, the strands run in opposite directions to permit base pairing between them, which is essential for replication or transcription of the encoded information.

The relative positions of structures along strands of nucleic acid, including genes and various protein binding sites, are usually noted as being either upstream (towards the 5′-end) or downstream (towards the 3′-end).

The mRNA is scanned by the ribosome from the 5′ end, where the start codon directs the incorporation of a methionine (bacteria, mitochondria, and plastids use N-formylmethionine instead) at the N terminus of the protein.

By convention, single strands of DNA and RNA sequences are written in a 5′-to-3′ direction except as needed to illustrate the pattern of base pairing.

To prevent unwanted nucleic acid ligation (e.g. self-ligation of a plasmid vector in DNA cloning), molecular biologists commonly remove the 5′-phosphate with a phosphatase.

Capping increases the stability of the messenger RNA while it undergoes translation, providing resistance to the degradative effects of exonucleases.

The 5′-untranslated region is the portion of the DNA starting from the cap site and extending to the base just before the AUG translation initiation codon of the main coding sequence.