Acid

In the special case of aqueous solutions, proton donors form the hydronium ion H3O+ and are known as Arrhenius acids.

A Brønsted or Arrhenius acid usually contains a hydrogen atom bonded to a chemical structure that is still energetically favorable after loss of H+.

Most acids encountered in everyday life are aqueous solutions, or can be dissolved in water, so the Arrhenius and Brønsted–Lowry definitions are the most relevant.

In 1884, Svante Arrhenius attributed the properties of acidity to hydrogen ions (H+), later described as protons or hydrons.

Thus, an Arrhenius acid can also be described as a substance that increases the concentration of hydronium ions when added to water.

An Arrhenius base, on the other hand, is a substance that increases the concentration of hydroxide (OH−) ions when dissolved in water.

In 1923, chemists Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Thomas Martin Lowry independently recognized that acid–base reactions involve the transfer of a proton.

In the second example CH3COOH undergoes the same transformation, in this case donating a proton to ammonia (NH3), but does not relate to the Arrhenius definition of an acid because the reaction does not produce hydronium.

In aqueous solution HCl behaves as hydrochloric acid and exists as hydronium and chloride ions.

A third, only marginally related concept was proposed in 1923 by Gilbert N. Lewis, which includes reactions with acid–base characteristics that do not involve a proton transfer.

For example, HCl has chloride as its anion, so the hydro- prefix is used, and the -ide suffix makes the name take the form hydrochloric acid.

[8] Superacids can permanently protonate water to give ionic, crystalline hydronium "salts".

It is often wrongly assumed that neutralization should result in a solution with pH 7.0, which is only the case with similar acid and base strengths during a reaction.

[15] Due to the successive dissociation processes, there are two equivalence points in the titration curve of a diprotic acid.

For a weak diprotic acid titrated by a strong base, the second equivalence point must occur at pH above 7 due to the hydrolysis of the resulted salts in the solution.

Many acids can be found in various kinds of food as additives, as they alter their taste and serve as preservatives.

The hydrochloric acid present in the stomach aids digestion by breaking down large and complex food molecules.

Human bodies contain a variety of organic and inorganic compounds, among those dicarboxylic acids play an essential role in many biological behaviors.

[22] Other weak acids serve as buffers with their conjugate bases to keep the body's pH from undergoing large scale changes that would be harmful to cells.

[23] The rest of the dicarboxylic acids also participate in the synthesis of various biologically important compounds in human bodies.

Nucleic acids contain the genetic code that determines many of an organism's characteristics, and is passed from parents to offspring.

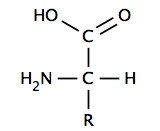

Aspartic acid, for example, possesses one protonated amine and two deprotonated carboxyl groups, for a net charge of −1 at physiological pH.

The cell membrane of nearly all organisms is primarily made up of a phospholipid bilayer, a micelle of hydrophobic fatty acid esters with polar, hydrophilic phosphate "head" groups.

Oxygen gas (O2) drives cellular respiration, the process by which animals release the chemical potential energy stored in food, producing carbon dioxide (CO2) as a byproduct.

Oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged in the lungs, and the body responds to changing energy demands by adjusting the rate of ventilation.

For example, during periods of exertion the body rapidly breaks down stored carbohydrates and fat, releasing CO2 into the blood stream.

It is the decrease in pH that signals the brain to breathe faster and deeper, expelling the excess CO2 and resupplying the cells with O2.

Cell membranes are generally impermeable to charged or large, polar molecules because of the lipophilic fatty acyl chains comprising their interior.

Acids that lose a proton at the intracellular pH will exist in their soluble, charged form and are thus able to diffuse through the cytosol to their target.

In vinylogous carboxylic acids, a carbon-carbon double bond separates the carbonyl and hydroxyl groups.