Adenomyosis

[18][19] The tissue injury and repair (TIAR) theory is now widely accepted and suggests that uterine hyperperistalsis (i.e., increased peristalsis), during early periods of reproductive life will induce micro-injury at the endometrial-myometrial interface (EMI) region.

At the same time, estrogen treatment will increase uterine peristalsis again, leading to a vicious circle and a chain of biological alterations essential for the development of adenomyosis.

Iatrogenic injury of the junctional zone or physical damage due to placental implantation most likely results in the same pathological cascade.

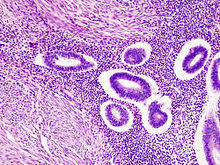

Several diagnostic criterion can be used, but typically they require either the endometrial tissue to have invaded greater than 2% of the myometrium, or a minimum invasion depth between 2.5 and 8mm.

[24] Transvaginal ultrasonography is a cheap and readily available imaging test that is typically used early during the evaluation of gynecologic symptoms.

[24] Doppler ultrasonography also serves to differentiate the static fluid within myometrial cysts from flowing blood within vessels.

[24] The junction zone (JZ), or a small distinct hormone-dependent region at the endometrial-myometrial interface, may be assessed by three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound (3D TVUS) and MRI.

[24] Interspersed within the thickened, darker signal of the junctional zone, one will often see foci of hyperintensity (bright spots) on the T2 weighted scans representing small cystically dilatated glands or more acute sites of microhemorrhage.

For women in their reproductive years, adenomyosis can typically be managed with the goals to provide pain relief, to restrict progression of the process, and to reduce significant menstrual bleeding.

Broadly speaking, surgical management of adenomyosis is split into two categories: uterine-sparing and non-uterine-sparing procedures.

Some uterine-sparing procedures have the benefit of improving fertility or retaining the ability to carry a pregnancy to term.

Non-uterine-sparing procedures, by definition, include surgical removal of the uterus and consequently they will all result in complete sterility.

[6] Hysterectomy, or surgical removal of the uterus, has historically been the primary method of diagnosing and treating adenomyosis.

These treatments, such as hormonal therapy and endometrial ablation, have significantly reduced the number of women who require a hysterectomy.

[6] There are many different types of hysterectomy, with varying options existing to removal the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and cervix.

For example, adenomyosis can increase the size of the uterus to such an extent that it physically cannot be removed through the vagina without first being cut into smaller pieces.

However, both entities could coexist and the endometrial tissue within the myometrium could harbor endometrioid adenocarcinoma, with potentially deep myometrial invasion.

[36] Given this, it is encouraged to screen women for adenomyosis by TVUS or MRI before starting assisted reproduction treatments (ART).