Ancient Regime of Spain

The Spanish institutions of the Ancien Régime were the superstructure that, with some innovations, but above all through the adaptation and transformation of the political, social and economic institutions and practices pre-existing in the different Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula in the Late Middle Ages, presided over the historical period that broadly coincides with the Modern Age: from the Catholic Monarchs to the Liberal Revolution (from the last third of the 15th century to the first third of the 18th century) and which was characterized by the features of the Ancien Régime in Western Europe: a strong monarchy (authoritarian or absolute), an estamental society and an economy in transition from feudalism to capitalism.

Shortly after the end of the Reconquest it forgets its military character, begins to act politically, with an intensity that finds its warmest point in the 17th century, and gradually its role is reduced to occupy exclusively diplomatic and honorary positions, both in the administration and in the Army, although this in a very general way, and as such quite distorting.

The early medieval repopulation process had granted an original freedom unparalleled in other parts of Europe (presuras, allods, behetrías), and more than in any other kingdom in the Castilian frontier or Extremadura, where the status of peasant was equated to that of nobleman if he defended his own land with a war horse (Caballeros Villanos).

The condition of the peasants, therefore, was not radically different in royalty and manor: neither in the former was freedom nor in the latter slavery.The involvement of the royal authority in municipal control became stronger at the end of the Middle Ages, as the monarchy became more authoritarian, especially after the crisis of the 14th century.

[6] The main revenues were always insufficient, so that the extraordinary emergency resources to loans from bankers (successively Castilian, German -the mythical Fugger-, Genoese and Portuguese) to the public debt (juros) and to monetary alterations were a chronic burden, which undermined the monarchy's credit and led it to periodic bankruptcies.

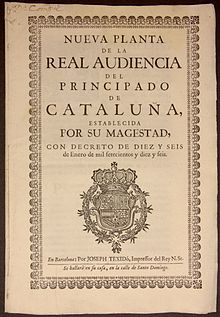

Prior to this, the Nueva Planta decrees had administratively unified Valencia and Catalonia without any difference with Castile (Aragon had already lost its fueros in the time of Philip II of Spain after the revolt of Antonio Perez), as a consequence of its defeat in the War of the Spanish Succession, which gave the opportunity to establish a tax system practically ex-novo without the obstacles of having to respect acquired rights, resulting in a simple and effective system that in fact stimulated economic activity during the 18th century while producing a substantial increase in tax collection.

First as the Secretariat of the Universal Office, since 1705 divided in two, and since 1714 in four (State, Treasury, Justice and one for War, Navy and the Indies), precedents of the structure in ministries and Council of Ministers with a President that will be typical of the Late modern period.

In any case, the work of the Secretaries who carried out the daily management of affairs had always been essential, and led to the formation of a class of scholars that allowed social ascent from non-privileged positions (or more commonly the lower nobility).

The Spanish taste for writing down every administrative act produced such an extensive volume of documentation that it has been exploited by hispanists from all over the world, in a kind of reverse brain drain, since they could not find similar deposits in their countries of origin.

The stage in which the Spanish economic-social formation was at each moment found in these institutions the catalyst that accelerated or slowed down the rhythm that the productive forces were imprinting on their particular transition from feudalism to capitalism during the Ancien Régime.

The War of the Castilian Succession, besides clarifying the dynastic union with Aragon and not with Portugal, made it clear that the only opportunity to maintain the authority of a king was his control of a military instrument at his exclusive service that could keep the nobles and cities in check, the better if it was so expensive that only by pushing the resources of the monarchy's treasury to the limit could it be paid for.

The traditional title of Constable of Castile – since 1382 the head of the armies, replacing the old position of ensign – was linked to the Fernández de Velasco family (Duke of Frías) and will play a more protocol role from the 17th century onwards.

The Capitulations of Santa Fe granted Christopher Columbus and his descendants the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea together with the viceroyalty of the lands to be discovered, but the recovery for the monarchy of the effective management of those functions was a matter of a few years.

Similar procedures were used with the so-called conquests in the American territory, an extension of the medieval cavalcades, and which in practice were political-military subcontracts to a particular of the rights that the monarchy was obsessively concerned with maintaining and justifying (the justos títulos and the reading of the famous Requirement).

[20] There was no police force worthy of the name until Ferdinand VII, who used it as an agency of political repression, and later even the Civil Guard (1844), which inherited many characteristics of the Santa Hermandad, such as territorial deployment with a preferably rural vocation.

Curiously, the only security corps in existence today that derives from the Ancien Régime is the Mossos d'Esquadra, recovered by the Autonomous Community of Catalonia, which was created as Escuadras de Paisanos Armados on 24 December 1721, with a rather inautonomist purpose: to maintain public order in substitution of the somatén and to put an end to the strongholds of miquelets supporting Charles of Austria.

In the time of Charles III and under the government of the Count of Aranda, a series of institutions were founded that would have great projection in the Contemporary Age, some symbolic: the Marcha Real (which would become the anthem of Spain) and the red and yellow banner (which replaced the white one with the Burgundy cross of St. Andrew in the Navy and ended up becoming the flag of Spain); and others substantive: the Royal Ordinances (Reales Ordenanzas para el Régimen, Disciplina, Subordinación y Servicio de sus Exércitos, of 22 October 1768)[22] and the extensive regulation of compulsory conscription by drawing quintas (1770),[23] an evolution of the already existing one, derived from the system of the Santa Hermandad (which obliged each town or group of towns to distribute one soldier for every one hundred inhabitants).

[25] The European policy of the Habsburgs, and Philip II's statement "I would rather lose my states than rule over heretics" was not only a senseless bleeding to death for the benefit of the Catholic faith, but a chain of tactical and strategic responses that fall within the imperial logic.

The political control of the clergy went beyond simple collaboration: the appointment of bishops obtained through the right of presentation, participation in ecclesiastical revenues (the royal third of the tithe, a tax more important than any of the civil ones) and, already in the 18th century, pressure on their properties (the so-called "first confiscation").

Proof of the deep religiosity that is supposed to the Catholic Monarch was the extreme importance that was granted to the election of the royal confessor, a real power in the Court for his capacity of access to the person of the king (sometimes considered little less than a favourite), and that it was customary to appoint among the members of a religious order (successively Franciscans, Hieronymites, Dominicans, Jesuits...). )

But the Church, as a hierarchical body, did not have a defined political action.As for the rest of the administration, the clergy (who remained, as in the Middle Ages, the most educated segment of the population) was used extensively: from the presidency of the Council of Castile, which was systematically entrusted to a bishop, to the requests for statistical information addressed to the parish priests.

In addition, all -in manor and in royalty- were obliged to pay religious taxes (tithes and first fruits), and in an extensive area of Galicia, Leon and Castile, they also paid the Voto de Santiago, which included the Patronage of Spain and its annual recognition by the king or his representative.

The local archpriestships and parishes closed the institutional base of the network of the secular clergy, very dense in the north of Spain and very dispersed in the south, with areas in Andalusia, La Mancha, Extremadura and Murcia where pastoral care was very deficient.

Simultaneously, there was an abundance of unedifying figures such as the beneficiary who accumulated the incomes of various benefices, the chaplains who sang mass with few or no assistants (apart from the altar boy) in the noble palaces, the tonsured clergy who did not exercise any curate or those who received minor orders for the sole purpose of acquiring ecclesiastical privileges.

The clerics regular were also similarly implanted throughout the territory, but subdivided into a large number of religious orders of various types, with monasteries (mostly in rural areas) and urban convents (dangerously taxing the local economy, as the municipalities complained, frequently requesting the limitation of new foundations).

[28] The proverbial relaxation of customs and poor formation of the late medieval clergy were the object of energetic reform programs: such as the Synod of Aguilafuente convoked by the Bishop of Segovia Juan Arias Dávila in 1472 (which gave rise to the first book printed in Spain, the Synodal of Aguilafuente), or the more general Council of Aranda convoked by Archbishop Carrillo in 1473; which did not prevent his successor in the see of Toledo, Cardinal Mendoza, known as the third king of Spain, from legitimizing his sons (the "beautiful little sins of the cardinal", according to Isabella the Catholic); or that the succession of the seat of Compostela fell first to the nephew of the previous archbishop and then to his son, linking three Alonsos de Fonseca who must be distinguished with ordinal numbers.

[29] The role of Cardinal Cisneros in the transition from the 15th to the 16th century was decisive for the Spanish Church to become a disciplined mechanism, little accessible to the innovations of the Lutheran reformation, although it did suffer the heartbreaking debate around Erasmism, which had much to do with the resistance to modernization in the religious orders.

In the 18th century, within a shameful intellectual decadence that allowed eccentricities such as those of Piscator Diego de Torres Villarroel from Salamanca, the main confrontation took place between the groups known as golillas and manteístas, with derivations to the later political careers of the university students.

State regulation of primary and secondary education had to wait for the Moyano Law, developed in the second half of the 19th century, although insufficient efforts were made to generalize schooling until the Second Spanish Republic, which sought to restrict the influence of the religious, triumphant again with the subsequent National Catholicism.

Dissidence in religious matters was the responsibility of a peculiar institution: the Spanish Inquisition, possibly the only one common to all of Spain, apart from the crown, and which, not having jurisdiction in the European kingdoms (the attempts to suffocate Protestantism in Flanders through its implantation were one of the causes of the success of its revolt) can really be considered as a shaping of the national personality, an extreme on which the anti-Spanish propaganda known as the Black Legend insisted.