Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus' reached its greatest extent under Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054); his sons assembled and issued its first written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda, shortly after his death.

Both meanings persisted in sources until the Mongol conquest: the narrower one, referring to the triangular territory east of the middle Dnieper, and the broader one, encompassing all the lands under the hegemony of Kiev's grand princes.

[36] There was once controversy over whether the Rus' were Varangians or Slavs (see anti-Normanism), however, more recently scholarly attention has focused more on debating how quickly an ancestrally Norse people assimilated into Slavic culture.

[4] This often unfruitful debate over origins has periodically devolved into competing nationalist narratives of dubious scholarly value being promoted directly by various government bodies in a number of states.

[39] More recently, in the context of resurgent nationalism in post-Soviet states, Anglophone scholarship has analyzed renewed efforts to use this debate to create ethno-nationalist foundation stories, with governments sometimes directly involved in the project.

[40] Conferences and publications questioning the Norse origins of the Rus' have been supported directly by state policy in some cases, and the resultant foundation myths have been included in some school textbooks in Russia.

[58]Modern scholars find this an unlikely series of events, probably made up by the 12th-century Orthodox priests who authored the Chronicle as an explanation how the Vikings managed to conquer the lands along the Varangian route so easily, as well as to support the legitimacy of the Rurikid dynasty.

[73] The new Kievan state prospered due to its abundant supply of furs, beeswax, honey and slaves for export,[74] and because it controlled three main trade routes of Eastern Europe.

[88] In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower Dniester and Dnieper rivers with the Tivertsi and the Ulichs, who were likely acting as vassals of the Magyars, blocking Rus' access to the Black Sea.

Prince Rastislav of Moravia had requested the Emperor to provide teachers to interpret the holy scriptures, so in 863 the brothers Cyril and Methodius were sent as missionaries, due to their knowledge of the Slavonic language.

[citation needed] The mission of Cyril and Methodius served both evangelical and diplomatic purposes, spreading Byzantine cultural influence in support of imperial foreign policy.

Constantine Porphyrogenitus described the annual course of the princes of Kiev, collecting tribute from client tribes, assembling the product into a flotilla of hundreds of boats, conducting them down the Dnieper to the Black Sea, and sailing to the estuary of the Dniester, the Danube delta, and on to Constantinople.

[111][112][non-primary source needed] The Chronicle reports that Prince Igor succeeded Oleg in 913, and after some brief conflicts with the Drevlians and the Pechenegs, a period of peace ensued for over twenty years.

[116][non-primary source needed] The Byzantines may have been motivated to enter the treaty out of concern of a prolonged alliance of the Rus', Pechenegs, and Bulgarians against them,[117] though the more favorable terms further suggest a shift in power.

[citation needed] It is not clearly documented when the title of grand prince was first introduced, but the importance of the Kiev principality was recognized after the death of Sviatoslav I in 972 and the ensuing struggle between Vladimir and Yaropolk.

[119] According to the Primary Chronicle, Vladimir assembled a host of Varangian warriors, first subdued the Principality of Polotsk and then defeated and killed Yaropolk, thus establishing his reign over the entire Kievan Rus' realm.

[120] As early as the 1st century AD, Greeks in the Black Sea Colonies converted to Christianity, and the Primary Chronicle even records the legend of Andrew the Apostle's mission to these coastal settlements, as well as blessing the site of present-day Kyiv.

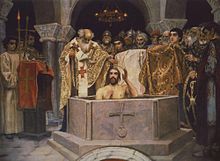

[121] The Primary Chronicle records the legend that when Vladimir had decided to accept a new faith instead of traditional Slavic paganism, he sent out some of his most valued advisors and warriors as emissaries to different parts of Europe.

[123] Vladimir's choice of Eastern Christianity may have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev's most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River.

'[127] According to historian Nancy Shields Kollmann, the rota system was used with the princely succession moving from elder to younger brother and from uncle to nephew, as well as from father to son.

Junior members of the dynasty usually began their official careers as rulers of a minor district, progressed to more lucrative principalities, and then competed for the coveted throne of Kiev.

[128] Whatever the case, according to professor Ivan Katchanovski 'no adequate system of succession to the Kievan throne was developed' after the death of Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054), commencing a process of gradual disintegration.

[citation needed] The rival Principality of Polotsk was contesting the power of the Grand Prince by occupying Novgorod, while Rostislav Vladimirovich was fighting for the Black Sea port of Tmutarakan belonging to Chernigov.

On the initiative of Vladimir II Monomakh in 1097 the Council of Liubech of Kievan Rus' took place near Chernigov with the main intention to find an understanding among the fighting sides.

The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, along which the goods were moving from the Black Sea (mainly Byzantine) through eastern Europe to the Baltic, was a cornerstone of Kievan wealth and prosperity.

After his death in 1132, Kievan Rus' fell into recession and a rapid decline, and Mstislav's successor Yaropolk II of Kiev, instead of focusing on the external threat of the Cumans, was embroiled in conflicts with the growing power of the Novgorod Republic.

[134] Now an independent city republic, and referred to as "Lord Novgorod the Great" it would spread its "mercantile interest" to the west and the north; to the Baltic Sea and the low-populated forest regions, respectively.

Later, as these territories, now part of modern central Ukraine and Belarus, fell to the Gediminids, the powerful, largely Ruthenized Grand Duchy of Lithuania drew heavily on the cultural and legal traditions of the Rus'.

When Vladimir assumed the throne, however, he set idols of Norse, Slav, Finn, and Iranian gods, worshipped by the disparate elements of his society, on a hilltop in Kiev in an attempt to create a single pantheon for his people.

'[168] According to Halperin (2010), 'Plokhy's approach does not invalidate analysis of rival claims by Muscovy, Lithuania or Ukraine to the Kievan inheritance; it merely relegates such pretensions entirely to the realm of ideology.