Franco-Provençal

In the late 20th century, it was proposed that the language be referred to under the neologism Arpitan (Franco-Provençal: arpetan; Italian: arpitano), and its areal as Arpitania.

[7] The use of both neologisms remains very limited, with most academics using the traditional form (often written without the hyphen: Francoprovençal), while language speakers refer to it almost exclusively as patois or under the names of its distinct dialects (Savoyard, Lyonnais, Gaga in Saint-Étienne, etc.).

Thus, commentators such as Désormaux consider "medieval" the terms for many nouns and verbs, including pâta "rag", bayâ "to give", moussâ "to lie down", all of which are conservative only relative to French.

France, Switzerland, the Franche-Comté (part of the Spanish Monarchy), and the duchy, later kingdom, ruled by the House of Savoy politically divided the region.

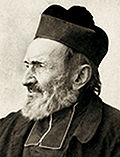

The name Franco-Provençal (franco-provenzale) is due to Graziadio Isaia Ascoli (1878), chosen because the dialect group was seen as intermediate between French and Provençal.

Graziadio Isaia Ascoli (1829–1907), a pioneering linguist, analyzed the unique phonetic and structural characteristics of numerous spoken dialects.

Ascoli (1878, p. 61) described the language in these terms in his defining essay on the subject: Chiamo franco-provenzale un tipo idiomatico, il quale insieme riunisce, con alcuni caratteri specifici, più altri caratteri, che parte son comuni al francese, parte lo sono al provenzale, e non proviene già da una confluenza di elementi diversi, ma bensì attesta sua propria indipendenza istorica, non guari dissimili da quella per cui fra di loro si distinguono gli altri principali tipi neo-latini.

I call Franco-Provençal a type of language that brings together, along with some characteristics which are its own, characteristics partly in common with French, and partly in common with Provençal, and are not caused by a late confluence of diverse elements, but on the contrary, attests to its own historical independence, little different from those by which the principal neo-Latin [Romance] languages distinguish themselves from one another.Although the name Franco-Provençal appears misleading, it continues to be used in most scholarly journals for the sake of continuity.

Suppression of the hyphen between the two parts of the language name in French (francoprovençal) was generally adopted following a conference at the University of Neuchâtel in 1969;[13] however, most English-language journals continue to use the traditional spelling.

Some contemporary speakers and writers prefer the name Arpitan because it underscores the independence of the language and does not imply a union to any other established linguistic group.

This is a colloquial term used because their ancestors were subjects of the Kingdom of Sardinia ruled by the House of Savoy until Savoie and Haute-Savoie were annexed by France in 1860.

Gaga (and the adjective gagasse) comes from a local name for the residents of Saint-Étienne, popularized by Auguste Callet's story "La légende des Gagats" published in 1866.

[24] Further, a regional law[25] passed by the government in Aosta requires educators to promote knowledge of Franco-Provençal language and culture in the school curriculum.

In 2005, the European Commission wrote that an approximate 68,000 people spoke the language in the Aosta Valley region of Italy, according to reports compiled after the 2003 linguistic survey conducted by the Fondation Chanoux.

[36] The Faetar and Cigliàje dialect was thought to be spoken by 1,400 people in an isolated pocket of the province of Foggia, in the southern Italian Apulia region.

[33] Beginning in 1951, strong emigration from the town of Celle Di San Vito to Canada established the Cigliàje variety of this dialect in Brantford, Ontario.

); 5) cinq; 6) siéx; 7) sèpt; 8) huét; 9) nô; 10) diéx; 11) onze'; 12) doze; 13) trèze; 14) quatôrze; 15) quinze; 16) sèze; 17) dix-sèpt; 18) dix-huét; 19) dix-nou; 20) vengt; 21) vengt-yon / vengt-et-yona; 22) vengt-dos ... 30) trenta; 40) quaranta; 50) cinquanta; 60) souessanta; 70) sèptanta; 80) huétanta; 90) nonanta; 100) cent; 1000) mila; 1,000,000) on milyon / on milyona.

The following is a list of all such toponyms: A long tradition of Franco-Provençal literature exists, although no prevailing written form of the language has materialized.

Among the first historical writings in Franco-Provençal are legal texts by civil law notaries that appeared in the 13th century as Latin was being abandoned for official administration.

Marguerite d'Oingt (c. 1240–1310), prioress of a Carthusian nunnery near Mionnay (France), composed two remarkable sacred texts in her native Lyonnais dialect, in addition to her writings in Latin.

The other work, Li Via seiti Biatrix, virgina de Ornaciu ("The Life of the Blessed Virgin Beatrix d'Ornacieux"), is a long biography of a nun and mystic consecrated to the Passion whose faith lead to a devout cult.

[43] A line from the work in her dialect follows:[44] Religious conflicts in Geneva between Calvinist Reformers and staunch Catholics, supported by the Duchy of Savoy, brought forth many texts in Franco-Provençal during the early 17th century.

These include: Bernardin Uchard (1575–1624), author and playwright from Bresse; Henri Perrin, comic playwright from Lyon; Jean Millet (1600?–1675), author of pastorals, poems, and comedies from Grenoble; Jacques Brossard de Montaney (1638–1702), writer of comedies and carols from Bresse; Jean Chapelon [frp] (1647–1694), priest and composer of more than 1,500 carols, songs, epistles, and essays from Saint-Étienne; and François Blanc dit Blanc la Goutte [fr] (1690–1742), writer of prose poems, including Grenoblo maléirou about the great flood of 1733 in Grenoble.

Her literary efforts encompassed lyrical themes, work, love, tragic loss, nature, the passing of time, religion, and politics, and are considered by many to be the most significant contributions to the literature.

The Concours Cerlogne Archived 9 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine – an annual event named in his honor – has focused thousands of Italian students on preserving the region's language, literature, and heritage since 1963.

At the end of the 19th century, regional dialects of Franco-Provençal were disappearing due to the expansion of the French language into all walks of life and the emigration of rural people to urban centers.

Cultural and regional savant societies began to collect oral folk tales, proverbs, and legends from native speakers in an effort that continues to today.

Prosper Convert [fr] (1852–1933), the bard of Bresse; Louis Mercier (1870–1951), folk singer and author of more than twelve volumes of prose from Coutouvre near Roanne; Just Songeon (1880–1940), author, poet, and activist from La Combe, Sillingy near Annecy; Eugénie Martinet [fr] (1896–1983), poet from Aosta; and Joseph Yerly [de] (1896–1961) of Gruyères whose complete works were published in Kan la têra tsantè ("When the earth sang"), are well known for their use of patois in the 20th century.

Louis des Ambrois de Nevache, from Upper Susa Valley, transcribed popular songs and wrote some original poetry in local patois.

There are compositions in the current language on the album Enfestar, an artistic project from Piedmont[47] The first comic book in a Franco-Provençal dialect, Le rebloshon que tyouè!