African Romance

[2] Evidence for a spoken Romance variety which developed locally out of Latin persisted in rural areas of Tunisia – possibly as late as the last two decades of the 15th century in some sources.

[23] The Romance philologist James Noel Adams lists a number of possible Africanisms found in this wider Latin literary corpus.

The African dialect included words such as ginga for "henbane", boba for "mallow," girba for "mortar" and gelela for the inner flesh of a gourd.

[30] The originally abstract word dulcor is seen applied as a probable medical African specialisation relating to sweet wine instead of the Latin passum or mustum.

[37] While modern scholars may express doubts on the interpretation or accuracy of some of these writings, they contend that African Latin must have been distinctive enough to inspire so much discussion.

[39] Loanwords from Northwest African Romance to Berber are attested, usually in the accusative form: examples include atmun ("plough-beam") from temonem.

[42] It was various parts of the littoral of Africa into the 12th century,[1] exerting a significant influence on Northwest African Arabic, particularly the language of northwestern Morocco.

[3] Christian cemeteries excavated in Kairouan dating from 945-1046 and in Áin Zára and En Ngila in Tripolitania from before the 10th century contain Latin inscriptions demonstrating continued use of written liturgical Latin centuries into Islamic rule; graves with Christian names such as Peter, John, Maria, Irene, Isidore, Speratus, Boniface and Faustinus contain common phrases such as "requiem aeternam det tibi Dominus et lux perpetua luceat tibi ("May the Lord give you eternal rest and everlasting light shine upon you") or Deus Sabaoth from the Sanctus hymn.

Another example attests to the dual usage of the Christian and the Hijri calendars, reading that the deceased died in Anno Domini 1007 or 397 annorum infidelium ("Year of the infidels".

[44] The Psalter notably contains spellings consistent with Vulgar Latin/African Romance features (see below), such as prothetic i insertion, repeated betacism in writing b for v and substituting second declension endings to undeclinable Semitic biblical names.

[45] Written Latin continued to be the language of correspondence between African bishops and the Papacy up till the final communication between Pope Gregory VII and the imprisoned archbishop of Carthage, Cyriacus in the 11th century.

)[48] There is also a possible reference to spoken Latin or African Romance in the 11th century, when the Rustamid governor Abu Ubayda Abd al-Hamid al-Jannawni was said to have sworn his oath of office in Arabic, Berber and in an unspecified "town language", which might be interpreted as a Romance variety; in the oath, the Arabic-rendered phrase bar diyyu could represent some variation of Latin per Deu(m) ("by God".

The 15th century Italian humanist Paolo Pompilio [it] makes the most significant remarks on the language and its features, reporting that a Catalan merchant named Riaria who had lived in North Africa for thirty years told him that the villagers in the Aurès mountain region "speak an almost intact Latin and, when Latin words are corrupted, then they pass to the sound and habits of the Sardinian language".

[51] The 16th century geographer and diplomat Leo Africanus, who was born into a Muslim family in Granada and fled the Reconquista to Morocco, also says that the North Africans retained their own language after the Islamic conquest which he calls "Italian", which must refer to Romance.

A potential linguistic relationship between Sardinia and North Africa could have been built up as a result of the two regions' long pre-Roman cultural ties starting from the 8th-7th centuries BC, when the island fell under the Carthaginian sphere of influence.

[E] The affinity between the two regions persisted after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire under shared governance by the Vandal Kingdom and then the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa.

[56] The spoken variety of African Romance was perceived to be similar to Sardinian as reported in the above-cited passage by Paolo Pompilio [it][F] – supporting hypotheses that there were parallelisms between developments of Latin in Africa and Sardinia.

The term cena pura is used by Augustine, although there is no evidence that its meaning in Africa extended beyond the Jewish religious context to simply refer to the day of Friday.

Apart from Sardinian, the only other Romance varieties which take their article from ipse/-a (instead of ille/-a) are the Catalan dialects of the Balearic islands and certain areas of Girona, the Vall de Gallerina and tàrbena, Provençal and medieval Gascon.

Blasco Ferrer proposes that usage of ipse/-a was preferred over ille/-a in Africa under southern Italian influence, as observed in the 2nd century Act of the Scillitan Martyrs (Passio Scillitanorum) which substitutes ipse/-a for ille/-a.

This dialectal form then could have developed into *tsa, which is attested in Old Catalan documents like the Homilies d'Organyà (e.g. za paraula: "the words"), and traversed the Mediterranean from Africa to Sardinia, the Balearics and southern Gaul.

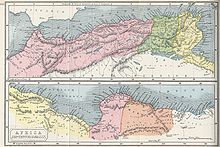

Although agreeing with previous studies that the Late Latin of the interior province of Africa Proconsularis certainly displayed Sardinian vocalism, Adamik argues based on inscriptional evidence that the vowel system was not uniform across the entirety of the North African coast, and there is some indication that the Latin variety of Mauretania Caesariensis was possibly changing in the direction of the asymmetric six-vowel system found in Eastern Romance languages such as Romanian: /a, ɛ, e, i, o, u/.

"[76] It is suggested that African Latin betacism may have pushed the phonological development of Ibero-Romance varieties in favor of the now characteristic Spanish b/v merger as well as influencing the lengthening of stressed short vowels (after the loss of vowel length distinction) evidenced in lack of diphthongization of short e/o in certain words (such as teneo > tengo ("I have"), pectus > pecho ("chest"), mons > monte ("mountain".

[78] Adamik also finds evidence for dialectological similarity between Hispania and Africa based on rates of errors in the case system, a relation which could have increased from the 4th-6th centuries AD but was disrupted by the Islamic invasion.

[83] Lameen Souag likewise compares several Maltese lexical items with Maghrebi Arabic forms to show that these words were borrowed directly from African Latin, rather than Italian or Sicilian.

[114] Scholars are uncertain or disagree on the Latin origin of some of the words presented in the list, which may be attributed alternatively to Berber language internal etymology.

[115] Scholars believe that there is a great number of Berber words, existing in various dialects, which are theorised to derive from late Latin or African Romance, such as the vocabulary in the following list.

It might be possible to reconstruct a chronology of which loans entered Berber languages in the Classical Latin period versus in Late Latin/Proto-Romance based on features; for example, certain forms such as afullus (from pullus, "chicken") or asnus (< asinus, "donkey") preserve the Classical Latin nominative ending -us, whereas other words like urṭu (< hortus, "garden") or muṛu (< murus, "wall") have lost final -s (matching parallel developments in Romance, perhaps in deriving from the accusative form after the loss of final -m.)[116] Forms such as tayda (< taeda, "pinewood"), which seem to preserve the Latin diphthong ae, might also be interpreted as archaic highly conservative loans from the Roman Imperial period or earlier.