Artificial bone

[4] Thus, to better help those in need to live a more comfortable life, engineers have been developing new techniques to produce and design better artificial bone structure and material.

[5] Increased research and knowledge regarding the organization, structure of properties of collagen and hydroxyapatite have led to many developments in collagen-based scaffolds in bone tissue engineering.

The structure of hydroxyapatite is very similar to that of the original bone, and collagen can act as molecular cables and further improve the biocompatibility of the implant.

The common causes for bone graft are tumor resection, congenital malformation, trauma, fractures, surgery, osteoporosis, and arthritis.

[8] Research on material types in bone grafting has been traditionally centered on producing composites of organic polysaccharides (chitin, chitosan, alginate) and minerals (hydroxyapatite).

Alginate scaffolds, composed of cross-linked calcium ions, are actively being explored in the regeneration of skin, liver, and bone.

[10] For applications that require a material with better toughness, nanostructured artificial nacre may be used due to its high tensile strength and Young's modulus.

Host cells of varying classifications, such as lymphocytes and erythrocytes, display minimal immunological response to artificial grafts.

Bioactivity, which is often gauged in terms of dissolution rates and the formation of a mineral layer on the implant surface in-vivo, can be enhanced in biomaterials, in particular hydroxyapatite, by modifying the composition and structure by doping.

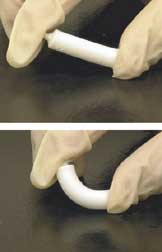

[5] Chitosan by itself can be easily modified into complex shapes that include porous structures, making it suitable for cell growth and osteoconduction.

[5] Chitosan can also be used with carbon nanotubes, which have a high Young's modulus (1.0–1.8 TPa), tensile strength (30–200 GPa), elongation at break (10–30%), and aspect ratio (>1,000).

Sintered materials increase the crystallinity of calcium phosphate in certain artificial bones, which leads to poor resorption by osteoclasts and compromised biodegradability.

[15] One study avoided this by creating inkjet-printed, custom-made artificial bones that utilized α-tricalcium phosphate (TCP), a material that converts to hydroxyapatite and solidifies the implant without the use of sintering.

Artificial grafts maintain comparable compressive strength, but occasionally lack similarity to human bone in response to lateral or frictional forces.

The study noted a slight decrease in compressive strength of the femurs, which could be attributed to imperfect printing and an increased ratio of cancellous bone.

Host cells of varying classifications, such as lymphocytes and erythrocytes, displayed minimal immunological response to artificial grafts.

The body's biological response to those materials depends on many parameters including chemical composition, topography, porosity, and grain size.

If the material is ceramic, it is difficult to form the desired shape, and bone can't reabsorb or replace it due to its high crystallinity.

[3] Hydroxyapatite, on the other hand, has shown excellent properties in supporting the adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation of osteogenesis cell since it is both thermodynamically stable and bioactive.

[3] Despite its excellent performance in interacting with bone tissue, hydroxyapatite has the same problem as ceramic in reabsorption due to its high crystallinity.