Atlas des Géographes d'Orbæ

One spent his entire life creating the five hundred and eight maps of the underground world of ants in his garden, while another died before completing the grand atlas of clouds, which included not only their shapes and colors but also their various ways of appearing and traveling.

At the annual fair where they come to town to trade their furs, Euphonos plays his lute, and they join their voices with his music, healing the lutenist from the deep-seated sorrow caused by his muteness.

As the missionary also has heterochromatic eyes, Three-Hearts-of-Stone invites him, if he wishes to preach, to take over his role by wearing the shaman's cloak, which is inhabited by misaligned spirits that inflict terrible suffering on its wearer.

To save his daughter, who was taken to be married to one of the young men before his sacrifice, the farmer and former soldier Tolkalk, visited in a dream by the gods, adds nine warriors sculpted from clay by his own hands to the vast terracotta army that lies dormant in a crypt under the mountains, thereby putting an end to the sacrificial tradition.

Kosmas agrees to accompany this long journey to the library, but the Stoners are met with suspicion in the villages of the Empire they pass through, and the scrolls are burned one night, leaving only the stone urns that contain them, vitrified by the fire.

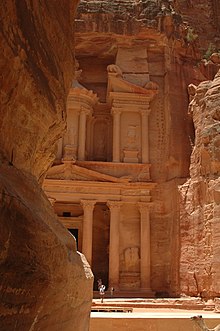

[25] In The Land of the Troglodytes, the photographer Hippolyte de Fontaride is transported with his equipment by local porters to the rugged landscapes where once a wealthy civilization thrived, living in cities carved into the rock and worshipping the moon.

The construction of a great clock by the talented master Jacob at the city's center gradually makes its inhabitants anxious and hurried, breaking the harmony they once shared with the river's natural cycles.

[29] In The Land of Xing-Li, renowned for its storytellers and tales, the old Huan never tires of hearing from an old woman the story of a Jade Emperor who fell madly in love with the portrait of an unknown young girl, to the point of abandoning his throne to spend his life searching for her.

Intrigued, Ortélius resumes this quest: using a flying machine inspired by Brazadîm's plans, he soars over the vast landscapes of Orbæ until he reaches an island in the middle of an ocean of grass.

[33] At the same time, the bibliographic research he conducted for his documentaries led him to gather abundant documentation on geographical atlases and travel stories, which in turn sparked his interest in the evolution of mentalities and the way different peoples meet, perceive, and understand each other.

Special attention is given to the chapter openings: the author initially plans for a large introductory image across two pages but ultimately chooses to pair it with a column of text to start the narrative right away while immersing the reader in the place he describes through the illustration.

[39] Another important task is to link the narratives together: since the goal is not to deliver a structured and homogeneous world but rather "fragments of travel," Place quickly discards the idea of a general map encompassing the twenty-six countries visited.

[1] Outside of France, the English translation of the first volume, titled A Voyage of Discovery,[note 5] received admiration from Philip Pullman, who regarded Place as an "extraordinary artist," describing the work as "prodigiously inventive" and a "triumph of imagination and mastery."

All of these elements create an ordered system structured around three main poles: the port city of Candaâ, which serves as the economic heart; The Land of Jade, a political and colonizing power; and the ideal Island of Orbæ, a cultural and spiritual center.

[75] Through these techniques, Place gives his work depth and coherence, making it a true universe—an idea reinforced by the very name of Orbæ, derived from the Latin orbs, orbis meaning "globe, world.

[55] Therefore, adopting multiple perspectives enriches the narrative and expresses an acceptance of the other in their difference:[89] the reader is invited to move beyond their dominant viewpoint and lose themselves in a labyrinth of peoples and cultures that must be apprehended in their diversity.

[91] While Place maintains a critical perspective throughout the Atlas, both on the flaws of Western civilization and on certain Indigenous customs (such as the cannibalism of the natives of The Island of Quinookta and the cruel religious tradition of the nomads in The Desert of Drums),[92] he frequently stages the defeat of imperialist Europe at the hands of Indigenous peoples:[91] the warriors of the Empire of the Five Cities defeat the conquistadors through dreams, the missionary who believes he has converted the people of Baïlabaïkal suddenly discovers he is the double of the old shaman, whom he must take on as his own,[93] and the settlers of The Land of the Yaléoutes fall victim to a glacier breaking off after having disrespected the old spiritual chief.

[94] The most significant episode in this regard is perhaps The Desert of Ultima, where the race organized by archetypical European powers to possess newly discovered lands—an explicit allegory of the colonial enterprise—is unexpectedly stopped by the sudden unleashing of natural elements.

[95] The author develops a dreamy and fabulous world intended to spark wonder in the reader:[96] shamans who control the natural elements, such as those from Ultima and The Land of the Yaléoutes,[92] an ivory dolphin that comes to life upon contact with seawater in the eyes of young Ziyara of Candaâ, two-hearted sorcerers who guard The Mandragore Mountains, the eerie The Island of Quinookta that engulfs the crew of a whaling ship and transforms their vessel into a ghost ship,[96] as well as laughing toads and trumpet-wielding otters.

[97] Beneath this appearance of factuality, which contrasts with the imagination at play, Place seeks to plunge the reader into doubt and wonder,[98] inviting them to be enchanted,[99] as evidenced by the numerous confrontations he stages between rationalist Western thinking and the magical words of indigenous peoples, which often triumph.

Similarly, the European settlers of The Land of the Yaléoutes, believing they can conquer the indigenous people through the sheer power of their firearms, see their ship destroyed by a falling glacier after threatening the old tribal sorcerer invoking the "word of the birds.

[100] The Atlas is permeated by a meditation on the hidden depths of the mind: for instance, The Mountain of Esmeralda portrays the victory of pre-Columbian warriors over the conquistadors, not through weapons, but because the latter were dreamt by the indigenous people.

This hermeneutic thesis, which views the universe in terms of the mind's disposition to seek profound meaning beyond appearances,[102] highlights humanity's tendency to extend its thought to the dimensions of reality.

[106] The power of the image, which expands the horizon and transports the viewer elsewhere, is evoked in the Atlas's narratives, for example, through the captivating painting of The Indigo Islands, contemplated by Cornélius in the Inn of Anatole Brazadîm,[note 9][106] and is directly applied in the illustrations, which complement the text[70] in a complementary rivalry.

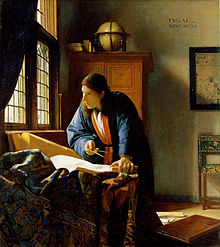

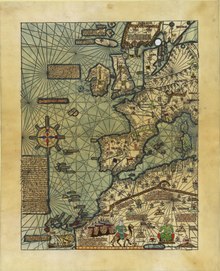

[107] As for the map, which is at the heart of the work since it is explicitly presented as the "Atlas of the Geographers of Orbæ,"[2] it is described in various ways: as an instrument of domination, giving control over space by making it readable and governable (according to Nîrdan Pacha, the cartographer engineer of The Mandragore Mountains); as mere pieces of paper blinding the cartographer, cutting him off from true knowledge of the terrain (according to the mandarg sorcerer in the same story); or as the fertile soil of the world, opening the doors to dreams (according to Ortélius, the cosmographer of Orbæ).

[110] Even more so, by reversing the logical process of representation in The Island of Orbæ, showing that his intervention on the Mother Map altered the degree of reality of the spaces depicted, the cosmographer advocates for a complete detachment from the real world and a surrender to creative imagination.

[33] This inspiration is so significant that Ortelius, co-founder with Mercator of Germanic cartography[109] and author of the 1570 Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the first printed cartographic collection (and therefore reproducible),[115] has his name taken for the main character of Orbæ.

[109] The immense Island of Orbæ itself represents Terra Australis, a vast continent that the Ancients believed extended to the south of the globe to balance the northern hemisphere's landmasses, which 16th-century cartographers like Ortelius included in their world maps.

[59] While references to cartographic history abound, other elements of the Atlas also point to figures of explorers and adventurers, such as the naturalist and geographer Alexander von Humboldt[109] (whose illustrated publications, which meticulously document his travels and discoveries, echo the general structure of the triptych), the brothers Jacques and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza (whose family name inspires that of Anatole Brazadîm in The Indigo Islands),[116] the sailor Alexander Selkirk[note 12] (whose name is evoked by John Macselkirk in The Island of Giants), the participants in the 1931-1932 "Yellow Cruise" automobile expedition (with the car race in Ultima offering an ironic reinterpretation),[91] and even Christopher Columbus, who, intending to sail to Asia, reached America (much like Ortelius, who, in The Land of the Zizotls, believes he's reaching The Indigo Islands, described as Eastern, but ends up in a seemingly Native American land).

[105] Specific allusions to other works appear within certain stories: The Mountain of Esmeralda is inspired by a Nahuatl text cited by Miguel León-Portilla, which tells the arrival of the conquistadors from the perspective of the indigenous peoples;[117] the expression "shell of humanity" used in a passage of The Frosted Land to describe the ice cave where the people of Nangajiik spend the polar night[note 14] echoes a line from Shakespeare's Hamlet,[note 15] where the metaphor of the shell symbolizes the human tendency to expand one's thought to the dimensions of reality;[102] the three main characters of The City of Vertigo—Izkadâr, Kholvino, and Buzodîn—are named after Ismaïl Kadaré, Italo Calvino, and Dino Buzzati, three authors whose works straddle the intersection of realism and the fantastic, much like Place's own;[39] and the epigraph of the Atlas on geography in Orbæ (see above) reprises a text that Jorge Luis Borges, master of South American magical realism, attributed to a fictional geographer from 1658.