Biochemical switches in the cell cycle

Such multi-component (involving multiple inter-linked proteins) switches have been shown to generate decisive, robust (and potentially irreversible) transitions and trigger stable oscillations.

An example that reveals the interaction of the multiple negative and positive feedback loops is the activation of cyclin-dependent protein kinases, or Cdks14.

The G1/S transition, more commonly known as the Start checkpoint in budding yeast (the restriction point in other organisms) regulates cell cycle commitment.

Active SBF/MBF drive the G1/S transition by turning on the B-type cyclins and initiating DNA replication, bud formation and spindle body duplication.

In the absence of coherent gene expression, cells take longer to exit G1 and a significant fraction even arrest before S phase, highlighting the importance of positive feedback in sharpening the G1/S switch.

Many different stimuli apply checkpoint controls including TGFb, DNA damage, contact inhibition, replicative senescence, and growth factor withdrawal.

[1] As mitosis starts, the nuclear envelope disintegrates, chromosomes condense and become visible, and the cell prepares for division.

This postulation was confirmed when Jin et al. employed Cdc2AF, an unphosphorylatable mutant of Cdk1, and saw accelerated entry to cell division due to the nuclear localization of the cyclin B.

To begin to investigate this, they first reconfirmed some of the results of the Jin et al. experiments, utilizing immunofluorescence to show cyclin B in the cytoplasm prior to division, and translocation to the nucleus to initiate mitosis, which they operationalized by comparing relative to nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB).

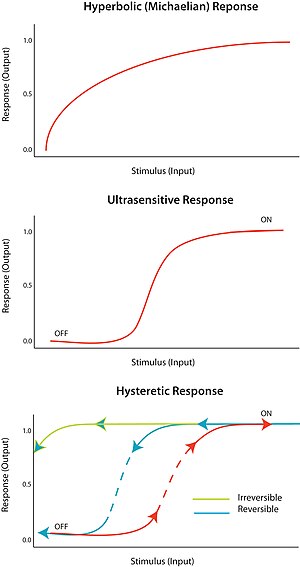

Coupling the bistable Cdk1 response function to the negative feedback from the APC could generate what is known as a relaxation oscillator,[4] with sharp spikes of Cdk1 activity triggering robust mitotic cycles.

In 2003 Pomerening et al. provided strong evidence for this hypothesis by demonstrating hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdk1 in the cytoplasmic extracts of Xenopus oocytes.

Which of the two steady states was occupied depended on the history of the system, i.e.whether they started with interphase or mitotic extract, effectively demonstrating hysteresis and bistability.

In the same year, Sha et al.[17] independently reached the same conclusion revealing the hysteretic loop also using Xenopus laevis egg extracts.

In this article, three predictions of the Novak-Tyson model were tested in an effort to conclude that hysteresis is the driving force for "cell-cycle transitions into and out of mitosis".

[1] Furthermore, the second prediction of the Novak-Tyson model was also validated: unreplicated deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, increases the threshold concentration of cyclin that is required to enter mitosis.

In order to arrive at this conclusion, cytostatic factor released extracts were supplemented with CHX, APH (a DNA polymerase inhibitor), or both, and non-degradable cyclin B was added.

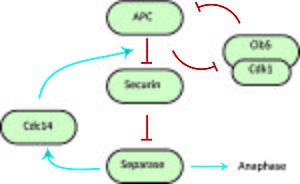

[18] In the transition from metaphase to anaphase, it is crucial that sister chromatids are properly and simultaneously separated to opposite ends of the cell.

As shown by Uhlmann et al., during the attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle the chromatids remain paired because cohesion between the sisters prevents separation.

In order to verify that Esp1 does play a role in regulating Scc1 chromosome association, cell strains were arrested in G1 with an alpha factor.

Esp1-1 mutant cells were used and the experiment was repeated, and Scc1 successfully bound to the chromosomes and remained associated even after the synthesis was terminated.

It has been shown by Holt et al.[5] that separase activates Cdc14, which in turn acts on securin, thus creating a positive feedback loop that increases the sharpness of the metaphase to anaphase transition and coordination of sister-chromatid separation.

This positive feedback can hypothetically generate bistability in the transition to anaphase, causing the cell to make the irreversible decision to separate sister-chromatids.

[22] Many speculations were made with regard to the control mechanisms employed by a cell to promote the irreversibility of mitotic exit in a eukaryotic model organism, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

[23] However, experiments using budding yeast cells with cdc28-as1, an INM-PP1 (ATP analog)-sensitive Cdk allele, proved that destruction of B-type cyclins (Clb) is not necessary for triggering irreversible mitotic exit.

[22] Clb2 degradation did shorten the Cdk1-inhibition period required for triggering irreversible mitotic exit indicating that cyclin proteolysis contributes to the dynamic nature of the eukaryotic cell cycle due to slower timescale of its action but is unlikely to be the major determining factor in triggering irreversible cell cycle transitions.

[22] Discoveries were made which indicated the importance of the level of the inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases in regulating eukaryotic cell cycle.

[22] Cdk1-inhibitors could induce mitotic exit even when degradation of B-type cyclins was blocked by expression of non-degradable Clbs or proteasome inhibitors.

Because eukaryotic cell cycle involves a variety of proteins and regulatory interactions, dynamical systems approach can be taken to simplify a complex biological circuit into a general framework for better analysis.

[36] Sic1 is a nice example demonstrating how systems-level feedbacks interact to sense the environmental conditions and trigger cell cycle transitions.

Using one-dimensional analysis, it might be possible to explain many of the irreversible transition points in the eukaryotic cell cycle that are governed by systems-level control and feedback.