Byzantine art

After the fall of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1453, art produced by Eastern Orthodox Christians living in the Ottoman Empire was often called "post-Byzantine."

Certain artistic traditions that originated in the Byzantine Empire, particularly in regard to icon painting and church architecture, are maintained in Greece, Cyprus, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia and other Eastern Orthodox countries to the present day.

One of the most important genres of Byzantine art was the icon, an image of Christ, the Virgin, or a saint, used as an object of veneration in Orthodox churches and private homes alike.

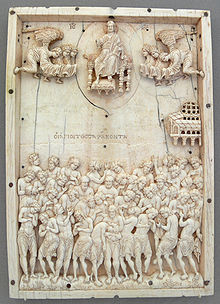

[15] Many of these were religious in nature, although a large number of objects with secular or non-representational decoration were produced: for example, ivories representing themes from classical mythology.

The term post-Byzantine is then used for later years, whereas "Neo-Byzantine" is used for art and architecture from the 19th century onwards, when the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire prompted a renewed appreciation of Byzantium by artists and historians alike.

Constantine devoted great effort to the decoration of Constantinople, adorning its public spaces with ancient statuary,[16] and building a forum dominated by a porphyry column that carried a statue of himself.

The most important surviving examples are the Madaba Map, the mosaics of Mount Nebo, Saint Catherine's Monastery and the Church of St Stephen in ancient Kastron Mefaa (now Umm ar-Rasas).

[48] Byzantine mosaicists probably also contributed to the decoration of the early Umayyad monuments, including the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus.

Ample literary sources indicate that secular art (i.e. hunting scenes and depictions of the games in the hippodrome) continued to be produced,[56] and the few monuments that can be securely dated to the period (most notably the manuscript of Ptolemy's "Handy Tables" today held by the Vatican[57]) demonstrate that metropolitan artists maintained a high quality of production.

The interior of Hagia Eirene, which is dominated by a large mosaic cross in the apse, is one of the best-preserved examples of iconoclastic church decoration.

Particularly important in this regard are the original mosaics of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen (since either destroyed or heavily restored) and the frescoes in the Church of Maria foris portas in Castelseprio.

In 867, the installation of a new apse mosaic in Hagia Sophia depicting the Virgin and Child was celebrated by the Patriarch Photios in a famous homily as a victory over the evils of iconoclasm.

Major surviving examples include Hosios Loukas in Boeotia, the Daphni Monastery near Athens and Nea Moni on Chios.

Byzantium had recently suffered a period of severe dislocation following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the subsequent loss of Asia Minor to the Turks.

The Komnenoi were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion, of which the Theotokos of Vladimir, the cycle of mosaics at Daphni, and the murals at Nerezi yield important examples.

Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the first time gained widespread popularity across the Empire.

Some of the finest Byzantine work of this period may be found outside the Empire: in the mosaics of Gelati, Kiev, Torcello, Venice, Monreale, Cefalù and Palermo.

For instance, Venice's Basilica of St Mark, begun in 1063, was based on the great Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, now destroyed, and is thus an echo of the age of Justinian.

Centuries of continuous Roman political tradition and Hellenistic civilization underwent a crisis in 1204 with the sacking of Constantinople by the Venetian and French knights of the Fourth Crusade, a disaster from which the Empire recovered in 1261 albeit in a severely weakened state.

As Nicaea emerged as the center of opposition under the Laskaris emperors, it spawned a renaissance, attracting scholars, poets, and artists from across the Byzantine world.

A glittering court emerged as the dispossessed intelligentsia found in the Hellenic side of their traditions a pride and identity unsullied by association with the hated "latin" enemy.

The icons, which became a favoured medium for artistic expression, were characterized by a less austere attitude, new appreciation for purely decorative qualities of painting and meticulous attention to details, earning the popular name of the Paleologan Mannerism for the period in general.

The Cretan school, as it is today known, gradually introduced Italian Renaissance elements into its style, and exported large numbers of icons to Italy.

Byzantine art was an essential part of this culture and had certain defining characteristics, such as intricate patterns, rich colors, and religious themes depicting important figures in Christianity.

Luxury products from the Empire were highly valued, and reached for example the royal Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo burial in Suffolk of the 620s, which contains several pieces of silver.

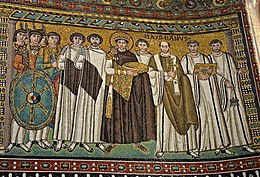

In particular, teams of mosaic artists were dispatched as diplomatic gestures by emperors to Italy, where they often trained locals to continue their work in a style heavily influenced by Byzantium.

The earliest surviving panel paintings in the West were in a style heavily influenced by contemporary Byzantine icons, until a distinctive Western style began to develop in Italy in the Trecento; the traditional and still influential narrative of Vasari and others has the story of Western painting begin as a breakaway by Cimabue and then Giotto from the shackles of the Byzantine tradition.

The Byzantine era properly defined came to an end with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, but by this time the Byzantine cultural heritage had been widely diffused, carried by the spread of Orthodox Christianity, to Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and, most importantly, to Russia, which became the centre of the Orthodox world following the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans.

Even under Ottoman rule, Byzantine traditions in icon-painting and other small-scale arts survived, especially in the Venetian-ruled Crete and Rhodes, where a "post-Byzantine" style under increasing Western influence survived for a further two centuries, producing artists including El Greco whose training was in the Cretan School which was the most vigorous post-Byzantine school, exporting great numbers of icons to Europe.

The willingness of the Cretan School to accept Western influence was atypical; in most of the post-Byzantine world "as an instrument of ethnic cohesiveness, art became assertively conservative during the Turcocratia" (period of Ottoman rule).