Capillary wave

A capillary wave is a wave traveling along the phase boundary of a fluid, whose dynamics and phase velocity are dominated by the effects of surface tension.

Capillary waves are common in nature, and are often referred to as ripples.

The wavelength of capillary waves on water is typically less than a few centimeters, with a phase speed in excess of 0.2–0.3 meter/second.

A longer wavelength on a fluid interface will result in gravity–capillary waves which are influenced by both the effects of surface tension and gravity, as well as by fluid inertia.

Ordinary gravity waves have a still longer wavelength.

Light breezes upon the surface of water which stir up such small ripples are also sometimes referred to as 'cat's paws'.

On the open ocean, much larger ocean surface waves (seas and swells) may result from coalescence of smaller wind-caused ripple-waves.

The dispersion relation describes the relationship between wavelength and frequency in waves.

Distinction can be made between pure capillary waves – fully dominated by the effects of surface tension – and gravity–capillary waves which are also affected by gravity.

For the boundary between fluid and vacuum (free surface), the dispersion relation reduces to When capillary waves are also affected substantially by gravity, they are called gravity–capillary waves.

Their dispersion relation reads, for waves on the interface between two fluids of infinite depth:[1][2] where

) waves (e.g. 2 mm for the water–air interface), which are proper capillary waves, do the opposite: an individual wave appears at the front of the group, grows when moving towards the group center and finally disappears at the back of the group.

[1] If one drops a small stone or droplet into liquid, the waves then propagate outside an expanding circle of fluid at rest; this circle is a caustic which corresponds to the minimal group velocity.

[5] There are three contributions to the energy, due to gravity, to surface tension, and to hydrodynamics.

The first two are potential energies, and responsible for the two terms inside the parenthesis, as is clear from the appearance of

For gravity, an assumption is made of the density of the fluids being constant (i.e., incompressibility), and likewise

(waves are not high enough for gravitation to change appreciably).

The third contribution involves the kinetic energies of the fluids.

Incompressibility is again involved (which is satisfied if the speed of the waves is much less than the speed of sound in the media), together with the flow being irrotational – the flow is then potential.

On one hand, the velocity must vanish well below the surface (in the "deep water" case, which is the one we consider, otherwise a more involved result is obtained, see Ocean surface waves.)

outside the parenthesis, which causes all regimes to be dispersive, both at low values of

An increase in area of the surface causes a proportional increase of energy due to surface tension:[7] where the first equality is the area in this (Monge's) representation, and the second applies for small values of the derivatives (surfaces not too rough).

must vanish well away from the surface (in the "deep water" case, which is the one we consider).

Using Green's identity, and assuming the deviations of the surface elevation to be small (so the z–integrations may be approximated by integrating up to

), the kinetic energy can be written as:[8] To find the dispersion relation, it is sufficient to consider a sinusoidal wave on the interface, propagating in the x–direction:[7] with amplitude

The kinematic boundary condition at the interface, relating the potentials to the interface motion, is that the vertical velocity components must match the motion of the surface:[7] To tackle the problem of finding the potentials, one may try separation of variables, when both fields can be expressed as:[7] Then the contributions to the wave energy, horizontally integrated over one wavelength

in the x–direction, and over a unit width in the y–direction, become:[7][10] The dispersion relation can now be obtained from the Lagrangian

is just the expression in the square brackets, so that the dispersion relation is: the same as above.

As a result, the average wave energy per unit horizontal area,

, is: As usual for linear wave motions, the potential and kinetic energy are equal (equipartition holds):

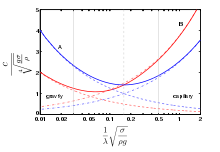

• Blue lines (A): phase velocity, Red lines (B): group velocity.

• Drawn lines: dispersion relation for gravity–capillary waves.

• Dashed lines: dispersion relation for deep-water gravity waves.

• Dash-dotted lines: dispersion relation valid for deep-water capillary waves.

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle {\sqrt[{4}]{g\sigma /\rho }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5fba378198fe7494e9310dfecd81b655747a78c)