Cell wall

While absent in many eukaryotes, including animals, cell walls are prevalent in other organisms such as fungi, algae and plants, and are commonly found in most prokaryotes, with the exception of mollicute bacteria.

Algae exhibit cell walls composed of glycoproteins and polysaccharides, such as carrageenan and agar, distinct from those in land plants.

[3] However, "the dead excrusion product of the living protoplast" was forgotten, for almost three centuries, being the subject of scientific interest mainly as a resource for industrial processing or in relation to animal or human health.

Carl Nägeli (1858, 1862, 1863) believed that the growth of the wall in thickness and in area was due to a process termed intussusception.

[7] In 1930, Ernst Münch coined the term apoplast in order to separate the "living" symplast from the "dead" plant region, the latter of which included the cell wall.

The flexibility of the cell walls is seen when plants wilt, so that the stems and leaves begin to droop, or in seaweeds that bend in water currents.

As John Howland explains Think of the cell wall as a wicker basket in which a balloon has been inflated so that it exerts pressure from the inside.

Other parts of plants such as the leaf stalk may acquire similar reinforcement to resist the strain of physical forces.

[16] They share the 1,3-β-glucan synthesis pathway with plants, using homologous GT48 family 1,3-Beta-glucan synthases to perform the task, suggesting that such an enzyme is very ancient within the eukaryotes.

Proteins embedded in cell walls are variable, contained in tandem repeats subject to homologous recombination.

[17] An alternative scenario is that fungi started with a chitin-based cell wall and later acquired the GT-48 enzymes for the 1,3-β-glucans via horizontal gene transfer.

The cellulose microfibrils are linked via hemicellulosic tethers to form the cellulose-hemicellulose network, which is embedded in the pectin matrix.

[21] In grass cell walls, xyloglucan and pectin are reduced in abundance and partially replaced by glucuronoarabinoxylan, another type of hemicellulose.

Secondary cell walls contain a wide range of additional compounds that modify their mechanical properties and permeability.

[23] The relative composition of carbohydrates, secondary compounds and proteins varies between plants and between the cell type and age.

The cells are held together and share the gelatinous membrane (the middle lamella), which contains magnesium and calcium pectates (salts of pectic acid).

Some of these groups (Oomycete and Myxogastria) have been transferred out of the Kingdom Fungi, in part because of fundamental biochemical differences in the composition of the cell wall.

Until recently they were widely believed to be fungi, but structural and molecular evidence[33] has led to their reclassification as heterokonts, related to autotrophic brown algae and diatoms.

[35] The spore wall has three layers, the middle one composed primarily of cellulose, while the innermost is sensitive to cellulase and pronase.

[38] The antibiotic penicillin is able to kill bacteria by preventing the cross-linking of peptidoglycan and this causes the cell wall to weaken and lyse.

The names originate from the reaction of cells to the Gram stain, a test long-employed for the classification of bacterial species.

[39] Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick cell wall containing many layers of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids.

Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall consisting of a few layers of peptidoglycan surrounded by a second lipid membrane containing lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins.

The beta-lactam antibiotics (e.g. penicillin, cephalosporin) only work against gram-negative pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

The glycopeptide antibiotics (e.g. vancomycin, teicoplanin, telavancin) only work against gram-positive pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus [41] Although not truly unique, the cell walls of Archaea are unusual.

[43] While the overall structure of archaeal pseudopeptidoglycan superficially resembles that of bacterial peptidoglycan, there are a number of significant chemical differences.

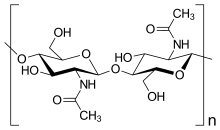

Like the peptidoglycan found in bacterial cell walls, pseudopeptidoglycan consists of polymer chains of glycan cross-linked by short peptide connections.

The result is an unstable structure that is stabilized by the presence of large quantities of positive sodium ions that neutralize the charge.

S-layers are common in bacteria, where they serve as either the sole cell-wall component or an outer layer in conjunction with polysaccharides.

Diatoms build a frustule from silica extracted from the surrounding water; radiolarians, foraminiferans, testate amoebae and silicoflagellates also produce a skeleton from minerals, called test in some groups.