Christianity in late antiquity

The Edict of Serdica was issued in 311 by the Roman emperor Galerius, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution of Christianity in the East.

His reforms attempted to create a form of religious heterogeneity by, among other things, reopening pagan temples, accepting Christian bishops previously exiled as heretics, promoting Judaism, and returning Church lands to their original owners.

However, although state persecution ended, by the early fifth century there was still much remaining prejudice within the empire against Christians: a popular proverb at the time was, according to Augustine of Hippo, "No rain!

Modalism (also called Sabellianism or Patripassianism) is the belief that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three different modes or aspects of God, as opposed to the Trinitarian view of three distinct persons or hypostases within the Godhead.

[13] Many groups held dualistic beliefs, maintaining that reality was composed into two radically opposing parts: matter, usually seen as evil, and spirit, seen as good.

Others held that both the material and spiritual worlds were created by God and were therefore both good, and that this was represented in the unified divine and human natures of Christ.

[15] Later Church Fathers wrote volumes of theological texts, including Augustine, Gregory Nazianzus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Ambrose of Milan, Jerome, and others.

These were mostly concerned with Christological disputes and represent an attempt to reach an orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christian theology.

The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism and affirmed the Blessed Virgin Mary to be Theotokos ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God").

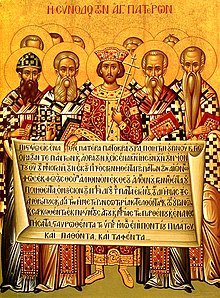

Emperor Constantine convened this council to settle a controversial issue, the relation between Jesus Christ and God the Father.

The council also addressed the issue of dating Easter (see Quartodecimanism and Easter controversy), recognised the right of the see of Alexandria to jurisdiction outside of its own province (by analogy with the jurisdiction exercised by Rome) and the prerogatives of the churches in Antioch and the other provinces[16] and approved the custom by which Jerusalem was honoured, but without the metropolitan dignity.

Even when Arius died in 336, one year before the death of Constantine, the controversy continued, with various separate groups espousing Arian sympathies in one way or another.

[18] In 359, a double council of Eastern and Western bishops affirmed a formula stating that the Father and the Son were similar in accord with the scriptures, the crowning victory for Arianism.

After quoting the Nicene Creed in its original form, as at the First Council of Nicaea, without the alterations and additions made at the First Council of Constantinople, it declared it "unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν) Faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicæa.

The council repudiated the Eutychian doctrine of Monophysitism, described and delineated the "Hypostatic Union" and two natures of Christ, human and divine; adopted the Chalcedonian Creed.

While there was a good measure of debate in the Early Church over the New Testament canon, the major writings were accepted by almost all Christians by the middle of the 2nd century.

[26] In his Easter letter of 367, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of exactly the same books as what would become the New Testament canon,[27] and he used the word "canonised" (kanonizomena) in regards to them.

[30] Pope Damasus I's Council of Rome in 382, if the Decretum Gelasianum is correctly associated with it, issued a biblical canon identical to that mentioned above,[27] or if not the list is at least a sixth-century compilation.

[36] After legalisation, the Church adopted the same organisational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called dioceses, corresponding to imperial governmental territorial division.

Peter and Paul had been martyred (killed), Constantinople was the "New Rome" where Constantine had moved his capital c. 330, and, lastly, all these cities had important relics.

By the 5th century, the ecclesiastical had evolved a hierarchical "pentarchy" or system of five sees (patriarchates), with a settled order of precedence, had been established.

[39] Though the appellate jurisdiction of the Pope, and the position of Constantinople, would require further doctrinal clarification, by the close of Antiquity the primacy of Rome and the sophisticated theological arguments supporting it were fully developed.

For at least twelve hundred years the Church of the East was noted for its missionary zeal, its high degree of lay participation, its superior educational standards and cultural contributions in less developed countries, and its fortitude in the face of persecution.

The Church of the East had its inception at a very early date in the buffer zone between the Roman Empire and the Parthian in Upper Mesopotamia.

[41] According to the fourth-century Western historian Rufinius, it was Frumentius who brought Christianity to Ethiopia (the city of Axum) and served as its first bishop, probably shortly after 325.

Until the decline of the Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes who had migrated there (with the exceptions of the Saxons, Franks, and Lombards, see below) had converted to Christianity.

During the later centuries following the Fall of Rome, as schism between the dioceses loyal to the Pope of Rome in the West and those loyal to the other Patriarchs in the East, most of the Germanic peoples (excepting the Crimean Goths and a few other eastern groups) would gradually become strongly allied with the Catholic Church in the West, particularly as a result of the reign of Charlemagne.

On Christmas 496,[47] however, Clovis I following his victory at the Battle of Tolbiac converted to the orthodox faith of the Catholic Church and let himself be baptised at Rheims.

It began early in the Church as a family of similar traditions, modeled upon Scriptural examples and ideals, and with roots in certain strands of Judaism.

St. John the Baptist is seen as the archetypical monk, and monasticism was also inspired by the organisation of the Apostolic community as recorded in Acts of the Apostles.