Coding region

[1] Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to non-coding regions over different species and time periods can provide a significant amount of important information regarding gene organization and evolution of prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

[5] The evidence suggests that there is a general interdependence between base composition patterns and coding region availability.

Short coding strands are comparatively still GC-poor, similar to the low GC-content of the base composition translational stop codons like TAG, TAA, and TGA.

The transitions are less likely to change the encoded amino acid and remain a silent mutation (especially if they occur in the third nucleotide of a codon) which is usually beneficial to the organism during translation and protein formation.

[10] There is also debate on whether the methods used, such as gene windows, to ascertain the relationship between GC-content and coding region are accurate and unbiased.

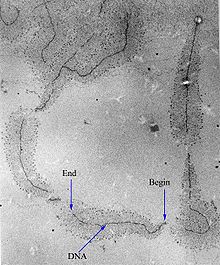

During transcription, the RNA Polymerase (RNAP) binds to the promoter sequence and moves along the template strand to the coding region.

RNAP then adds RNA nucleotides complementary to the coding region in order to form the mRNA, substituting uracil in place of thymine.

[13] The tRNAs transfer their associated amino acids to the growing polypeptide chain, eventually forming the protein defined in the initial DNA coding region.

[17] RNA splicing ultimately determines what part of the sequence becomes translated and expressed, and this process involves cutting out introns and putting together exons.

[21] There exist multiple transcription and translation mechanisms to prevent lethality due to deleterious mutations in the coding region.

[24] These patterns of constraint between genomes may provide clues to the sources of rare developmental diseases or potentially even embryonic lethality.

Clinically validated variants and de novo mutations in CCRs have been previously linked to disorders such as infantile epileptic encephalopathy, developmental delay and severe heart disease.

In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, gene overlapping occurs relatively often in both DNA and RNA viruses as an evolutionary advantage to reduce genome size while retaining the ability to produce various proteins from the available coding regions.