Crossover experiment (chemistry)

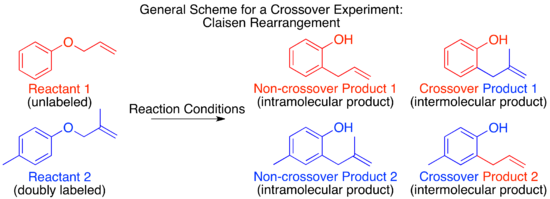

The aim of a crossover experiment is to determine whether or not a reaction process involves a stage where the components of each reactant have an opportunity to exchange with each other.

The results of crossover experiments are often straightforward to analyze, making them one of the most useful and most frequently applied methods of mechanistic study.

[4] When the mechanism being investigated is more complicated than an intra- or intermolecular substitution or rearrangement, crossover experiment design can itself become a challenging question.

Mechanistic studies are of interest to theoretical and experimental chemists for a variety of reasons including prediction of stereochemical outcomes, optimization of reaction conditions for rate and selectivity, and design of improved catalysts for better turnover number, robustness, etc.

Only a handful of experimental methods are capable of providing information about the mechanism of a reaction, including crossover experiments, studies of the kinetic isotope effect, and rate variations by substituent.

[1] It can be difficult to know whether or not the changes made to reactants for a crossover experiment will affect the mechanism by which the reaction proceeds.

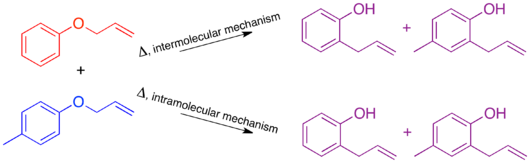

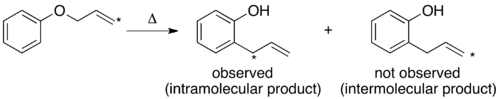

The mechanism of the thermal Claisen rearrangement has been studied by crossover experiment and serves as an excellent example of how to apply this technique.

For a non-isotopic labeling method the smallest perturbation to the system will be by addition of a methyl group at an unreactive position.

For the Claisen rearrangement, labeling by addition of a single methyl group produces an under-labeled system.

The resulting crossover experiment would not be useful as a mechanistic study since the products of an intermolecular or intramolecular mechanism are identical.

In this case it is also important to explicitly predict the relative amounts of the label expected to appear at each position depending on the mechanism.

Since the expected product of an intermolecular mechanism is not observed the conclusion matches that of the traditional crossover experiment.

Mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy are the two most common ways of determining the products and their relative ratios.

IR spectroscopy can be useful in specialized situations, such as when 13CO was used to probe the mechanism of alkyl insertion into metal-carbon monoxide bonds to form metal-acyl complexes.

Tracking the 13CO in the products was accomplished using IR spectroscopy because the greater mass of 13C compared to 12C produces a distinctive shift of the ν(CO) stretching frequency to lower energy.

If the results do not match any expected distribution, it is necessary to consider alternate mechanisms and/or the possibility that the labeling has affected the way the reaction proceeds.

The design of a useful crossover experiment relies on having a proposed mechanism on which to base predictions of the label distribution in the products.

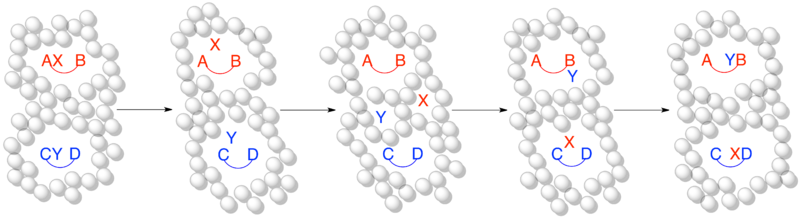

One of the major limitations of the crossover experiment is that it cannot rule out the possibility that solvent cage effects are masking a dissociation mechanism.

When protio- and deutero-azomethane are combined and irradiated in the gas phase, the result is a statistical mixture of the expected non-crossover and crossover radical recombination products, C2H6, CH3CD3, and C2D6, as 1:2:1.

[12][13] This demonstrated that the solvent cage effect is capable of significantly altering the results of a crossover experiment, especially on short-timescale reactions such as those involving radicals.

In the work of E.L. Muetterties on dirhenium decacarbonyl, a crossover experiment was carried out using 185Re and 187Re to determine the mechanism of substitution reactions of rhenium carbonyl dimers.

The results of these experiments lead to the conclusion that the catalytic cycle of this important click reaction involves a dinuclear copper intermediate.

In catalytic cycles that form C-H or C-C bonds reductive elimination is often the final product-forming step.

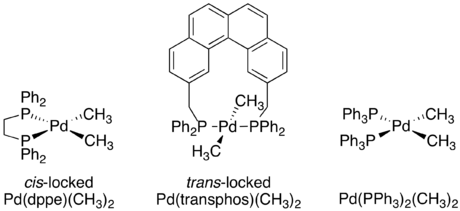

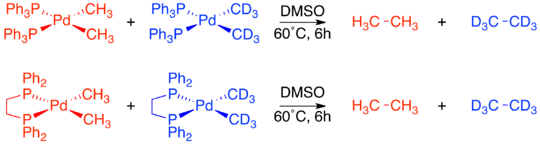

[18] Square planar d8 metal complexes are often the active catalysts in C-H or C-C bond forming reactions, and reductive elimination from these species is well understood.

[4] Regardless of the specific mechanism, it is consistently true that reductive elimination is an intramolecular process that couples two adjacent ligands.

To determine whether or not this reductive elimination was also constrained to only adjacent ligands, an isotope labeling experiment was carried out.

This led to the final conclusion that only ligands adjacent to each other on the metal complex are capable of reductively eliminating.

[4][19] This study also tracked and analyzed reaction rate data, demonstrating the value of employing multiple strategies in a concerted effort to gain as much information as possible about a chemical process.

The ability of the reaction to produce intermolecular transfer of tritium at this position indicates that the proton removed from citrate does not exchange with solvent.

A similar experiment reacting [2-18OH]isocitrate with aconitase failed to produce isotopically labeled citrate, demonstrating that the hydroxyl group, unlike the removed proton, exchanges with solvent every turnover.