DNA supercoil

[1] The amount of supercoiling in a given strand is described by a mathematical formula that compares it to a reference state known as "relaxed B-form" DNA.

In a "relaxed" double-helical segment of B-DNA, the two strands twist around the helical axis once every 10.4–10.5 base pairs of sequence.

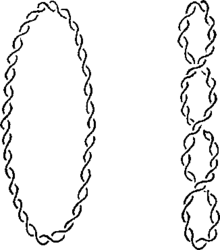

If a DNA segment under twist strain is closed into a circle by joining its two ends, and then allowed to move freely, it takes on different shape, such as a figure-eight.

The two lobes of the figure eight will appear rotated either clockwise or counterclockwise with respect to one another, depending on whether the helix is over- or underwound.

[2] Lobal contortions of a circular DNA, such as the rotation of the figure-eight lobes above, are referred to as writhe.

Many topoisomerase enzymes sense supercoiling and either generate or dissipate it as they change DNA topology.

For larger molecules it is common for hybrid structures to form – a loop on a toroid can extend into a plectoneme.

In that study, Sytox Orange (an intercalating dye) was used to induce supercoiling on surface tethered DNA molecules.

In prokaryotes, plectonemic supercoils are predominant, because of the circular chromosome and relatively small amount of genetic material.

DNA packaging is greatly increased during mitosis when duplicated sister DNAs are segregated into daughter cells.

It has been shown that condensin, a large protein complex that plays a central role in mitotic chromosome assembly, induces positive supercoils in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner in vitro.

[7][8] Supercoiling could also play an important role during interphase in the formation and maintenance of topologically associating domains (TADs).

[13] Specialized proteins can unzip small segments of the DNA molecule when it is replicated or transcribed into RNA.

Also, transcription itself contorts DNA in living human cells, tightening some parts of the coil and loosening it in others.

This model is illustrated in the figure, where reactions 1 represent transcription and its locking due to supercoiling.

This number is physically "locked in" at the moment of covalent closure of the chromosome, and cannot be altered without strand breakage.

If there is a closed DNA molecule, the sum of Tw and Wr, or the linking number, does not change.

Since biological circular DNA is usually underwound, Lk will generally be less than Tw, which means that Wr will typically be negative.

A standard expression independent of the molecule size is the "specific linking difference" or "superhelical density" denoted σ, which represents the number of turns added or removed relative to the total number of turns in the relaxed molecule/plasmid, indicating the level of supercoiling.

Negative supercoiling is also thought to favour the transition between B-DNA and Z-DNA, and moderate the interactions of DNA binding proteins involved in gene regulation.

[22][23] In general, such models include a promoter, Pro, which is the region of DNA controlling transcription and, thus, whose activity/locking is affected by PSB.

This can be done by having some component in the system that is produced over time (e.g., during transcription events) to represent positive supercoils, and that is removed by the action of Gyrases.

In standard texts, these properties are invariably explained in terms of a helical model for DNA, but in 2008 it was noted that each topoisomer, negative or positive, adopts a unique and surprisingly wide distribution of three-dimensional conformations.

[4] When the sedimentation coefficient, s, of circular DNA is ascertained over a large range of pH, the following curves are seen.

The DNA, now in the state known as Form IV, remains extremely dense, even if the pH is restored to the original physiologic range.

As stated previously, the structure of Form IV is almost entirely unknown, and there is no currently accepted explanation for its extraordinary density.

These behaviors of Forms I and IV are considered to be due to the peculiar properties of duplex DNA which has been covalently closed into a double-stranded circle.

If the covalent integrity is disrupted by even a single nick in one of the strands, all such topological behavior ceases, and one sees the lower Form II curve (Δ).

For Form II, alterations in pH have very little effect on s. Its physical properties are, in general, identical to those of linear DNA.

The separated single strands have slightly different s values, but display no significant changes in s with further increases in pH.