Regulation of gene expression

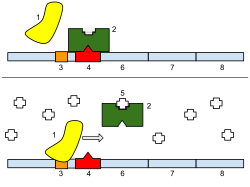

Sophisticated programs of gene expression are widely observed in biology, for example to trigger developmental pathways, respond to environmental stimuli, or adapt to new food sources.

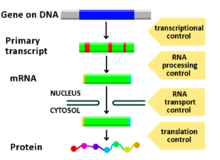

Virtually any step of gene expression can be modulated, from transcriptional initiation, to RNA processing, and to the post-translational modification of a protein.

Gene regulation is essential for viruses, prokaryotes and eukaryotes as it increases the versatility and adaptability of an organism by allowing the cell to express protein when needed.

Although as early as 1951, Barbara McClintock showed interaction between two genetic loci, Activator (Ac) and Dissociator (Ds), in the color formation of maize seeds, the first discovery of a gene regulation system is widely considered to be the identification in 1961 of the lac operon, discovered by François Jacob and Jacques Monod, in which some enzymes involved in lactose metabolism are expressed by E. coli only in the presence of lactose and absence of glucose.

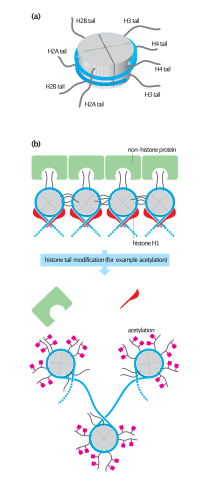

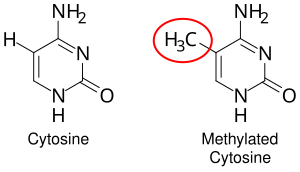

The following is a list of stages where gene expression is regulated, where the most extensively utilized point is transcription initiation, the first stage in transcription:[citation needed] In eukaryotes, the accessibility of large regions of DNA can depend on its chromatin structure, which can be altered as a result of histone modifications directed by DNA methylation, ncRNA, or DNA-binding protein.

Octameric protein complexes called histones together with a segment of DNA wound around the eight histone proteins (together referred to as a nucleosome) are responsible for the amount of supercoiling of DNA, and these complexes can be temporarily modified by processes such as phosphorylation or more permanently modified by processes such as methylation.

Analysis of the pattern of methylation in a given region of DNA (which can be a promoter) can be achieved through a method called bisulfite mapping.

The differences are analyzed by DNA sequencing or by methods developed to quantify SNPs, such as Pyrosequencing (Biotage) or MassArray (Sequenom), measuring the relative amounts of C/T at the CG dinucleotide.

While this lncRNA ultimately affects gene expression in neuronal disorders such as Parkinson, Huntington, and Alzheimer disease, others, such as, PNCTR(pyrimidine-rich non-coding transcriptors), play a role in lung cancer.

The number of lncRNAs in the human genome remains poorly defined, but some estimates range from 16,000 to 100,000 lnc genes.

They occur on genomic DNA and histones and their chemical modifications regulate gene expression in a more efficient manner.

Chronic nicotine intake in mice alters brain cell epigenetic control of gene expression through acetylation of histones.

The majority of the differentially methylated CpG sites returned to the level of never-smokers within five years of smoking cessation.

In rodent models, drugs of abuse, including cocaine,[15] methamphetamine,[16][17] alcohol[18] and tobacco smoke products,[19] all cause DNA damage in the brain.

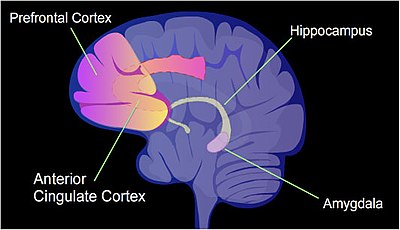

[23] Cytosine methylation is altered in the promoter regions of about 9.17% of all genes in the hippocampus neuron DNA of a rat that has been subjected to a brief fear conditioning experience.

The pattern of induced and repressed genes within neurons appears to provide a molecular basis for forming the first transient memory of this training event in the hippocampus of the rat brain.

Cells do this by modulating the capping, splicing, addition of a Poly(A) Tail, the sequence-specific nuclear export rates, and, in several contexts, sequestration of the RNA transcript.

Three prime untranslated regions (3'-UTRs) of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) often contain regulatory sequences that post-transcriptionally influence gene expression.

By binding to specific sites within the 3'-UTR, miRNAs can decrease gene expression of various mRNAs by either inhibiting translation or directly causing degradation of the transcript.

As of 2014, the miRBase web site,[29] an archive of miRNA sequences and annotations, listed 28,645 entries in 233 biologic species.

[34] For instance, in gastrointestinal cancers, a 2015 paper identified nine miRNAs as epigenetically altered and effective in down-regulating DNA repair enzymes.

In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, a large number of RNA binding proteins exist, which often are directed to their target sequence by the secondary structure of the transcript, which may change depending on certain conditions, such as temperature or presence of a ligand (aptamer).

[42] In general, most experiments investigating differential expression used whole cell extracts of RNA, called steady-state levels, to determine which genes changed and by how much.