Diels–Alder reaction

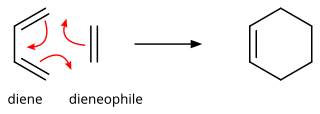

Through the simultaneous construction of two new carbon–carbon bonds, the Diels–Alder reaction provides a reliable way to form six-membered rings with good control over the regio- and stereochemical outcomes.

[1][2] Consequently, it has served as a powerful and widely applied tool for the introduction of chemical complexity in the synthesis of natural products and new materials.

[3][4] The underlying concept has also been applied to π-systems involving heteroatoms, such as carbonyls and imines, which furnish the corresponding heterocycles; this variant is known as the hetero-Diels–Alder reaction.

As such, the Diels–Alder reaction is governed by orbital symmetry considerations: it is classified as a [π4s + π2s] cycloaddition, indicating that it proceeds through the suprafacial/suprafacial interaction of a 4π electron system (the diene structure) with a 2π electron system (the dienophile structure), an interaction that leads to a transition state without an additional orbital symmetry-imposed energetic barrier and allows the Diels–Alder reaction to take place with relative ease.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of Diels–Alder reactions exhibit stereospecific, syn addition of the two components, a diradical intermediate has been postulated[7] (and supported with computational evidence) on the grounds that the observed stereospecificity does not rule out a two-step addition involving an intermediate that collapses to product faster than it can rotate to allow for inversion of stereochemistry.

There is a notable rate enhancement when certain Diels–Alder reactions are carried out in polar organic solvents such as dimethylformamide and ethylene glycol,[13] and even in water.

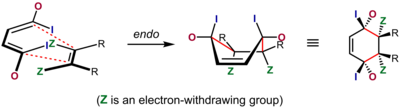

For intermolecular reactions especially, the preferred positional and stereochemical relationship of substituents of the two components compared to each other are controlled by electronic effects.

However, for intramolecular Diels–Alder cycloaddition reactions, the conformational stability of the structure of the transition state can be an overwhelming influence.

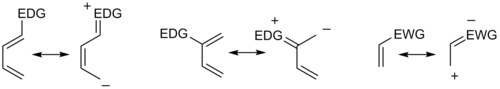

Frontier molecular orbital theory has also been used to explain the regioselectivity patterns observed in Diels–Alder reactions of substituted systems.

Examining the canonical mesomeric forms above, it is easy to verify that these results are in accord with expectations based on consideration of electron density and polarization.

In general, with respect to the energetically most well-matched HOMO-LUMO pair, maximizing the interaction energy by forming bonds between centers with the largest frontier orbital coefficients allows the prediction of the main regioisomer that will result from a given diene-dienophile combination.

For instance, in uncommon combinations involving X groups on both diene and dienophile, a 1,3-substitution pattern may be favored, an outcome not accounted for by a simplistic resonance structure argument.

[21] The most widely accepted explanation for the origin of this effect is a favorable interaction between the π systems of the dienophile and the diene, an interaction described as a secondary orbital effect, though dipolar and van der Waals attractions may play a part as well, and solvent can sometimes make a substantial difference in selectivity.

[29] It has particular synthetic utility as means of furnishing α,β–unsaturated cyclohexenone systems by elimination of the 1-methoxy substituent after deprotection of the enol silyl ether.

In contrast, stable dienes, such as naphthalene, require forcing conditions and/or highly reactive dienophiles, such as N-phenylmaleimide.

Anthracene, being less aromatic (and therefore more reactive for Diels–Alder syntheses) in its central ring can form a 9,10 adduct with maleic anhydride at 80 °C and even with acetylene, a weak dienophile, at 250 °C.

The problem is that ketene itself cannot be used in Diels–Alder reactions because it reacts with dienes in unwanted manner (by [2+2] cycloaddition), and therefore "masked functionality" approach has to be used.

In addition, the Lewis acid catalyst also increases the asynchronicity of the Diels–Alder reaction, making the occupied π-orbital located on the C=C double bond of the dienophile asymmetric.

Thus, indeed Lewis acid catalysts strengthen the normal electron demand orbital interaction by lowering the LUMO of the dienophile, but, they simultaneously weaken the inverse electron demand orbital interaction by also lowering the energy of the dienophile's HOMO.

[6] Evans' oxazolidinones,[52] oxazaborolidines,[53][54][55] bis-oxazoline–copper chelates,[56] imidazoline catalysis,[57] and many other methodologies exist for effecting diastereo- and enantioselective Diels–Alder reactions.

The Diels-Alder reaction was the culmination of several intertwined research threads, some near misses, and ultimately, the insightful recognition of a general principle by Otto Diels and Kurt Alder.

[62][63] However, the history of the reaction extends further back, revealing a fascinating narrative of discoveries missed and opportunities overlooked.

[64] Several chemists, working independently in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, encountered reactions that, in retrospect, involved the Diels-Alder process but remained unrecognized as such.

[64] While these observations hinted at the possibility of a broader class of cycloaddition reactions, they remained isolated incidents, their significance not fully appreciated at the time, with none of the researchers even trying to generalize their findings.

Unlike the earlier researchers, they recognized the generality and predictability of the diene and dienophile combining to form a cyclic structure.

Conversion of the cis-aldehyde to its corresponding alkene by Wittig olefination and subsequent ring-closing metathesis with a Schrock catalyst gave the second ring of the alkaloid core.

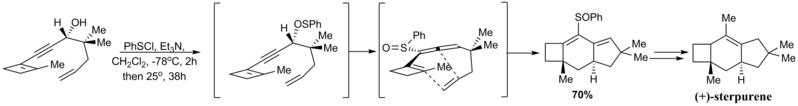

The [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of the thiophenyl group to give the sulfoxide as below proceeded enantiospecifically due to the predefined stereochemistry of the propargylic alcohol.

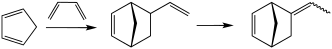

Thermally initiated, conrotatory opening of the benzocyclobutene generated the o-quinodimethane, which reacted intermolecularly to give the tetracycline skeleton.