Economic history of Mexico

As the crown began limiting the encomienda in the mid-sixteenth century to prevent the development of an independent seigneurial class through the New Laws, Spaniards who had become landowners acquired permanent and part-time labor from Indigenous and mixed-race workers.

[25] Great haciendas did not completely dominate the agrarian sector, since there were products that could be efficiently produced by smaller holders and indigenous villages, such as fruits and vegetables, cochineal red dye, and animals that could be raised in confined spaces, such as pigs and chickens.

Yucatán was more easily accessed from Cuba than Mexico City, but it had a dense Maya population so there was a potential labor force to produce products such as sugar, cacao, and later henequen (sisal).

The larger the amount of mercury used in refining, the greater pure silver was extracted from ore. Another important element for the eighteenth-century economic boom was the number of wealthy Mexicans who were involved in multiple enterprises as owners, investors, or creditors.

Only those defined as Spaniards, either peninsular- or American-born of legitimate birth had access to a variety of elite privileges such as civil office holding, ecclesiastical positions, but also entrance of women into convents, which necessitated a significant dowry.

He recommended that the crown press for major changes in the agrarian sector, including the breakup of entailed estates, sale of common lands to individuals, and other instruments to make agriculture more profitable.

In 1810, with the massive revolt led by secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo rapidly expanded into a social upheaval of Indigenous and mixed-race castas that targeted Spaniards (both peninsular-born and American-born) and their properties.

The weakness of the state contrasts with the strength of Roman Catholic Church in Mexico, which was the exclusive religious institution with spiritual power, but it was also a major holder of real estate and source of credit for Mexican elites.

However, according to Hilarie J. Heath, the results were bleak: The early republic has often been called the "Age of Santa Anna," a military hero, participant in the coup ousting emperor Augustín I during Mexico's brief post-independence monarchy.

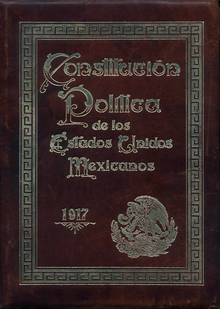

When the Mexican republic was established in 1824, noble titles were eliminated, however, special privileges (fueros) of two corporate groups, churchmen and the military, remained in force so that there were differential legal rights and access to courts.

Faced with political disruptions, civil wars, unstable currency, and the constant threat of banditry in the countryside, most wealthy Mexicans invested their assets in the only stable productive enterprises that remained viable: large agricultural estates with access to credit from the Catholic Church.

The Church could have loaned money for industrial enterprises, the costs and risks of starting one in the circumstances of bad transportation and lack of consumer spending power or demand meant that agriculture was a more prudent investment.

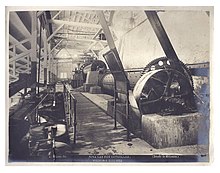

[75] In October, 1835, the Conservative Party intellectual and statesman Lucas Alaman, the Banco de Avío, a state owned bank was established in order to provide pecuniary aid and machinery to Mexico's industry and agriculture.

The government issued contracts for construction of a new rail line northward to the United States, and in 1873 completed the commercially vital Mexico City–Veracruz railroad, begun in 1837 but disrupted by civil wars and the French invasion from 1850 to 1868.

The family of future Mexican president Francisco I. Madero developed successful enterprises in the Comarca Lagunera region, which spans the states of Coahuila and Durango, where cotton was commercially grown.

Madero sought to interest fellow large landowners in the region in pushing for the construction of a high dam to control periodic flooding along the Nazas River, and increase agricultural production there.

Enterprises sourced their merchandise from abroad, using British, German, Belgian, and Swiss suppliers, but they also sold textiles made in their own factories in Mexico, creating a level of vertical integration.

For the peasants in Morelos, a sugar-growing area close to Mexico City, Madero's slowness to make good on his promise to restore village lands prompted a revolt against the government.

Concessions made to foreign oil during the Porfiriato were a particularly difficult matter in the post-Revolutionary period, but General and President Alvaro Obregón negotiated a settlement in 1923, the Bucareli Treaty, that guaranteed petroleum enterprises already built in Mexico.

Calles stepped in to form in 1929 the Partido Nacional Revolucionario, the precursor to the Institutional Revolutionary Party, helped stabilize the political and economic system, creating a mechanism to manage conflicts and set the stage for more orderly presidential elections.

According to a 2017 study, "Key US and Mexican officials recognized that an IMF program of currency devaluation and austerity would probably fail in its stated objective of reducing Mexico's balance of payments deficit.

Nevertheless, US Treasury and Federal Reserve officials, fearing that a Mexican default might lead to bank failures and subsequent global financial crisis, intervened to an unprecedented degree in the negotiations between the IMF and Mexico.

The United States offered direct financial support and worked through diplomatic channels to insist that Mexico accept an IMF adjustment program, as a way of bailing out US banks.

By mid-1981, Mexico was beset by falling oil prices, higher world interest rates, rising inflation, an overvalued peso, and a deteriorating balance of payments that spurred massive capital flight.

Widespread fears that the government might fail to achieve fiscal balance and have to expand the money supply and raise taxes deterred private investment and encouraged massive capital flight that further increased inflationary pressures.

By 1988 (de la Madrid's final year as President) inflation was at last under control, fiscal and monetary discipline attained, relative price adjustment achieved, structural reform in trade and public-sector management underway, and the economy was bound for recovery.

In April 1989, President Carlos Salinas de Gortari announced his government's national development plan for 1989–94, which called for annual GDP growth of 6 percent and an inflation rate similar to those of Mexico's main trading partners.

The following year, Salinas took his next step toward higher capital inflows by lowering domestic borrowing costs, reprivatizing the banking system, and broaching the idea of a free-trade agreement with the United States.

During 1993 the economy grew by a negligible amount, but growth rebounded to almost 4 percent during 1994, as fiscal and monetary policy were relaxed and foreign investment was bolstered by United States ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

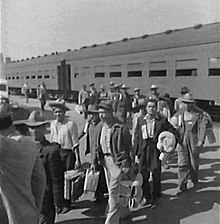

On 1 January 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect and on the same day, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in Chiapas took several small towns, belying Mexico's assurances that the government created the conditions for stability.