Electronic band structure

Band theory has been successfully used to explain many physical properties of solids, such as electrical resistivity and optical absorption, and forms the foundation of the understanding of all solid-state devices (transistors, solar cells, etc.).

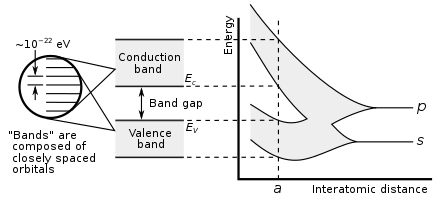

For example, the bands associated with core orbitals (such as 1s electrons) are extremely narrow due to the small overlap between adjacent atoms.

Special high symmetry points/lines in the Brillouin zone are assigned labels like Γ, Δ, Λ, Σ (see Fig 1).

It is difficult to visualize the shape of a band as a function of wavevector, as it would require a plot in four-dimensional space, E vs. kx, ky, kz.

[7][8] Another method for visualizing band structure is to plot a constant-energy isosurface in wavevector space, showing all of the states with energy equal to a particular value.

These are somewhat more difficult to study theoretically since they lack the simple symmetry of a crystal, and it is not usually possible to determine a precise dispersion relation.

As a result, virtually all of the existing theoretical work on the electronic band structure of solids has focused on crystalline materials.

These low-energy core bands are also usually disregarded since they remain filled with electrons at all times, and are therefore inert.

The bands and band gaps near the Fermi level are given special names, depending on the material: The ansatz is the special case of electron waves in a periodic crystal lattice using Bloch's theorem as treated generally in the dynamical theory of diffraction.

The consequences of periodicity are described mathematically by the Bloch's theorem, which states that the eigenstate wavefunctions have the form

Here index n refers to the nth energy band, wavevector k is related to the direction of motion of the electron, r is the position in the crystal, and R is the location of an atomic site.

[12]: 179 The NFE model works particularly well in materials like metals where distances between neighbouring atoms are small.

This tight binding model assumes the solution to the time-independent single electron Schrödinger equation

Band structures of materials like Si, GaAs, SiO2 and diamond for instance are well described by TB-Hamiltonians on the basis of atomic sp3 orbitals.

In transition metals a mixed TB-NFE model is used to describe the broad NFE conduction band and the narrow embedded TB d-bands.

[15][16] The most important features of the KKR or Green's function formulation are (1) it separates the two aspects of the problem: structure (positions of the atoms) from the scattering (chemical identity of the atoms); and (2) Green's functions provide a natural approach to a localized description of electronic properties that can be adapted to alloys and other disordered system.

The simplest form of this approximation centers non-overlapping spheres (referred to as muffin tins) on the atomic positions.

[17] It is commonly believed that DFT is a theory to predict ground state properties of a system only (e.g. the total energy, the atomic structure, etc.

[18] In practice, however, no known functional exists that maps the ground state density to excitation energies of electrons within a material.

In principle time-dependent DFT can be used to calculate the true band structure although in practice this is often difficult.

A popular approach is the use of hybrid functionals, which incorporate a portion of Hartree–Fock exact exchange; this produces a substantial improvement in predicted bandgaps of semiconductors, but is less reliable for metals and wide-bandgap materials.

[19] To calculate the bands including electron-electron interaction many-body effects, one can resort to so-called Green's function methods.

For real systems like solids, the self-energy is a very complex quantity and usually approximations are needed to solve the problem.

One such approximation is the GW approximation, so called from the mathematical form the self-energy takes as the product Σ = GW of the Green's function G and the dynamically screened interaction W. This approach is more pertinent when addressing the calculation of band plots (and also quantities beyond, such as the spectral function) and can also be formulated in a completely ab initio way.

The GW approximation seems to provide band gaps of insulators and semiconductors in agreement with experiment, and hence to correct the systematic DFT underestimation.

However, materials such as CoO that have an odd number of electrons per unit cell are insulators, in direct conflict with this result.

This kind of material is known as a Mott insulator, and requires inclusion of detailed electron-electron interactions (treated only as an averaged effect on the crystal potential in band theory) to explain the discrepancy.

It can be treated non-perturbatively within the so-called dynamical mean-field theory, which attempts to bridge the gap between the nearly free electron approximation and the atomic limit.

Calculating band structures is an important topic in theoretical solid state physics.

The tight binding model is extremely accurate for ionic insulators, such as metal halide salts (e.g. NaCl).