Evolutionary developmental biology

The field grew from 19th-century beginnings, where embryology faced a mystery: zoologists did not know how embryonic development was controlled at the molecular level.

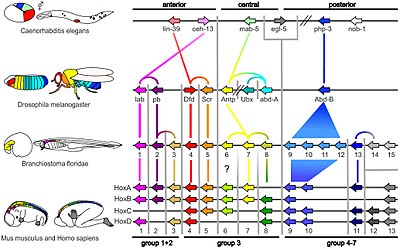

These genes are ancient, being highly conserved among phyla; they generate the patterns in time and space which shape the embryo, and ultimately form the body plan of the organism.

This multiple pleiotropic reuse explains why these genes are highly conserved, as any change would have many adverse consequences which natural selection would oppose.

Another possibility is the neo-Lamarckian theory that epigenetic changes are later consolidated at gene level, something that may have been important early in the history of multicellular life.

Aristotle argues instead that the process has a predefined goal: that the "seed" that develops into the embryo began with an inbuilt "potential" to become specific body parts, such as vertebrae.

The embryologist Karl Ernst von Baer opposed this, arguing in 1828 that there was no linear sequence as in the great chain of being, based on a single body plan, but a process of epigenesis in which structures differentiate.

Von Baer instead recognized four distinct animal body plans: radiate, like starfish; molluscan, like clams; articulate, like lobsters; and vertebrate, like fish.

For example, Darwin cited in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species the shrimp-like larva of the barnacle, whose sessile adults looked nothing like other arthropods; Linnaeus and Cuvier had classified them as molluscs.

[10][11] Darwin also noted Alexander Kowalevsky's finding that the tunicate, too, was not a mollusc, but in its larval stage had a notochord and pharyngeal slits which developed from the same germ layers as the equivalent structures in vertebrates, and should therefore be grouped with them as chordates.

The Russian biochemist Boris Belousov had run experiments with similar results, but was unable to publish them because scientists thought at that time that creating visible order violated the second law of thermodynamics.

[19] In the so-called modern synthesis of the early 20th century, between 1918 and 1930 Ronald Fisher brought together Darwin's theory of evolution, with its insistence on natural selection, heredity, and variation, and Gregor Mendel's laws of genetics into a coherent structure for evolutionary biology.

As the gaps in the fossil record had been used as an argument against Darwin's gradualist evolution, de Beer's explanation supported the Darwinian position.

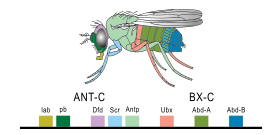

[31][32] In 1978, Edward B. Lewis discovered homeotic genes that regulate embryonic development in Drosophila fruit flies, which like all insects are arthropods, one of the major phyla of invertebrate animals.

[33] Bill McGinnis quickly discovered homeotic gene sequences, homeoboxes, in animals in other phyla, in vertebrates such as frogs, birds, and mammals; they were later also found in fungi such as yeasts, and in plants.

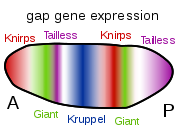

[36] In 1980, Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus described gap genes which help to create the segmentation pattern in fruit fly embryos;[37][38] they and Lewis won a Nobel Prize for their work in 1995.

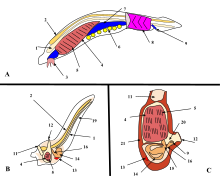

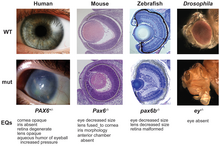

[34][39] Later, more specific similarities were discovered: for example, the distal-less gene was found in 1989 to be involved in the development of appendages or limbs in fruit flies,[40] the fins of fish, the wings of chickens, the parapodia of marine annelid worms, the ampullae and siphons of tunicates, and the tube feet of sea urchins.

It was evident that the gene must be ancient, dating back to the last common ancestor of bilateral animals (before the Ediacaran Period, which began some 635 million years ago).

[41][42] Roughly spherical eggs of different animals give rise to unique morphologies, from jellyfish to lobsters, butterflies to elephants.

Many of these organisms share the same structural genes for body-building proteins like collagen and enzymes, but biologists had expected that each group of animals would have its own rules of development.

Their bodies are patterned by a system of switching which causes development of different features to begin earlier or later, to occur in this or that part of the embryo, and to continue for more or less time.

The step-by-step control of its embryogenesis was visualized by attaching fluorescent dyes of different colours to specific types of protein made by genes expressed in the embryo.

These transcription factors contain the homeobox protein-binding DNA motif, also found in other toolkit genes, and create the basic pattern of the body along its front-to-back axis.

[50][51][52] The protein products of the regulatory toolkit are reused not by duplication and modification, but by a complex mosaic of pleiotropy, being applied unchanged in many independent developmental processes, giving pattern to many dissimilar body structures.

[53][54] The Bicoid, Hunchback and Caudal proteins in turn regulate the transcription of gap genes such as giant, knirps, Krüppel, and tailless in a striped pattern, creating the first level of structures that will become segments.

The interactions of transcription factors and cis-regulatory elements, or of signalling proteins and receptors, become locked in through multiple usages, making almost any mutation deleterious and hence eliminated by natural selection.

[56][57] Among the more surprising and, perhaps, counterintuitive (from a neo-Darwinian viewpoint) results of recent research in evolutionary developmental biology is that the diversity of body plans and morphology in organisms across many phyla are not necessarily reflected in diversity at the level of the sequences of genes, including those of the developmental genetic toolkit and other genes involved in development.

Epigenetic changes include modification of DNA by reversible methylation,[71] as well as nonprogrammed remoulding of the organism by physical and other environmental effects due to the inherent plasticity of developmental mechanisms.

[78] Researchers study concepts and mechanisms such as developmental plasticity, epigenetic inheritance, genetic assimilation, niche construction and symbiosis.