Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

This development ultimately led, directly after this period, to broad Mesopotamian unification under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire.

These new findings revealed that Lower Mesopotamia shared many socio-cultural developments with neighboring areas and that the entirety of the ancient Near East participated in an exchange network in which material goods and ideas were being circulated.

[2] The periodization was developed in the 1930s during excavations that were conducted by Henri Frankfort on behalf of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute at the archaeological sites of Tell Khafajah, Tell Agrab, and Tell Asmar in the Diyala Region of Iraq.

Research in Syria has shown that developments there were quite different from those in the Diyala river valley region or southern Iraq, rendering the traditional Lower Mesopotamian chronology useless.

[2][3] The ED was preceded by the Jemdet Nasr and then succeeded by the Akkadian period, during which, for the first time in history, large parts of Mesopotamia were united under a single ruler.

According to later Mesopotamian historical tradition, this was the time when legendary mythical kings such as Lugalbanda, Enmerkar, Gilgamesh, and Aga ruled over Mesopotamia.

[20] For example, the peace treaty between Entemena of Lagash and Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk, recorded on a clay nail, represents the oldest known agreement of this kind.

For example, the reigns of legendary figures like king Gilgamesh of Uruk and his adversaries Enmebaragesi and Aga of Kish possibly date to ED II.

[27] In March 2020, archaeologists announced the discovery of a 5,000-year-old cultic area filled with more than 300 broken ceremonial ceramic cups, bowls, jars, animal bones and ritual processions dedicated to Ningirsu at the site of Girsu.

Along with neighboring areas, this region was home to Scarlet Ware—a type of painted pottery characterized by geometric motifs representing natural and anthropomorphic figures.

[36][38] The period seems to have experienced a phase of decentralization, as reflected by the absence of large monumental buildings and complex administrative systems similar to what had existed at the end of the fourth millennium BC.

Starting in 2700 BC and accelerating after 2500, the main urban sites grew considerably in size and were surrounded by towns and villages that fell inside their political sphere of influence.

Many sites in Upper Mesopotamia, including Tell Chuera and Tell Beydar, shared a similar layout: a main tell surrounded by a circular lower town.

[citation needed] Among the important sites of this period are Tell Brak (Nagar), Tell Mozan, Tell Leilan, and Chagar Bazar in the Jezirah and Mari on the middle Euphrates.

According to the excavator of Mari, the circular city on the middle Euphrates was founded ex nihilo at the time of the Early Dynastic I period in Lower Mesopotamia.

The archives of Ebla, capital city of a powerful kingdom during the ED IIIb period, indicated that writing and the state were well-developed, contrary to what had been believed about this area before its discovery.

Due to the absence of written evidence and a lack of archaeological excavations targeting this period, the socio-political situation of Proto-Elamite Iran is not well understood.

[citation needed] In the middle third millennium BC, Elam emerged as a powerful political entity in the area of southern Lorestan and northern Khuzestan.

[45] The areas further north and to the east were important participants in the international trade of this period due to the presence of tin (central Iran and the Hindu Kush) and lapis lazuli (Turkmenistan and northern Afghanistan).

The artifacts found in the royal tombs of the First Dynasty of Ur indicate that foreign trade was particularly active during this period, with many materials coming from foreign lands, such as Carnelian likely coming from the Indus or Iran, Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan, silver from Turkey, copper from Oman, and gold from several locations such as Egypt, Nubia, Turkey or Iran.

The Code of Urukagina has also been widely hailed as the first recorded example of government reform, as it sought to achieve a higher level of freedom and equality.

Goods such as obsidian from Turkey, lapis lazuli from Badakhshan in Afghanistan, beads from Bahrain, and seals inscribed with the Indus Valley script from India have been found in Ur.

Gold items discovered included personal ornaments, weapons, tools, sheet-metal cylinder seals, fluted bowls, goblets, imitation cockle shells, and sculptures.

Lapis lazuli has been found in items such as jewelry, plaques, gaming boards, lyres, ostrich-egg vessels, and also in parts of a larger sculpture known as Ram in a Thicket.

The Sumerian style clearly influenced neighbouring regions, as similar statues have been recovered from sites in Upper Mesopotamia, including Assur, Tell Chuera, and Mari.

[41][8] Examples include the votive relief of king Ur-Nanshe of Lagash and his family found at Girsu and that of Dudu, a priest of Ningirsu.

The most remarkable gold objects come from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, including musical instruments and the complete inventory of Puabi’s tomb.

This variety disappeared at the start of the third millennium, to be replaced by an almost exclusive focus on mythological and cultural scenes in Lower Mesopotamia and the Diyala region.

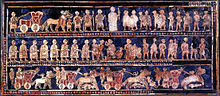

[8] Examples of inlay have been found at several sites and used materials such as nacre (mother of pearl), white and coloured limestone, lapis lazuli, and marble.

It is our source of the most information on this practice in ancient Mesopotamia [74] Similar mosaic elements were discovered at Mari, where a mother-of-pearl engraver's workshop was identified, and at Ebla where marble fragments were found from a 3-meter-high panel decorating a room of the royal palace.