First Persian invasion of Greece

Consisting of two distinct campaigns, the invasion of the independent Greek city-states was ordered by the Persian king Darius the Great, who sought to punish Athens and Eretria after they had supported the earlier Ionian Revolt.

Additionally, Darius also saw the subjugation of Greece as an opportunity to expand into Southeast Europe and thereby ensure the security of the Achaemenid Empire's western frontier.

The expedition headed first to Naxos, which was captured and burned, and then leapfrogged between the rest of the Cycladic Islands, annexing each of them into the Achaemenid Empire.

The unfinished business from this campaign led Darius to prepare for a much larger invasion of Greece, aimed at firmly subjugating it and punishing Athens and Sparta.

[8] As the British author Tom Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally.

[15] The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus.

[18][22] However, the Ionian Revolt had directly threatened the integrity of the Persian empire, and the states of mainland Greece remained a potential menace to its future stability.

[23][24] The Ionian revolt had begun with an unsuccessful expedition against Naxos, a joint venture between the Persian satrap Artaphernes and the Miletus tyrant Aristagoras.

[27] The involvement of Athens in the Ionian Revolt arose from a complex set of circumstances, beginning with the establishment of the Athenian Democracy in the late 6th century BC.

Cleisthenes's reasons for suggesting such a radical course of action, which would remove much of his own family's power, are unclear; perhaps he perceived that days of aristocratic rule were coming to an end anyway; certainly he wished to prevent Athens becoming a puppet of Sparta by whatever means necessary.

[31] The new-found freedom and self-governance of the Athenians meant that they were thereafter exceptionally hostile to the return of the tyranny of Hippias, or any form of outside subjugation; by Sparta, Persia or anyone else.

[32] Cleomenes's attempts to restore Isagoras to Athens ended in a debacle, but fearing the worst, the Athenians had by this point already sent an embassy to Artaphernes in Sardis, to request aid from the Persian Empire.

Despite the fact their actions were ultimately fruitless, the Eretrians and in particular the Athenians had earned Darius's lasting enmity, and he vowed to punish both cities.

[39] The revolt was used as an opportunity by Darius to extend the empire's border to the islands of the East Aegean[40] and the Propontis, which had not been part of the Persian dominions before.

[41] The completion of the pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece, and to punish Athens and Eretria.

[42] In the spring of 492 BC an expeditionary force, to be commanded by Darius's son-in-law Mardonius, was assembled, consisting of a fleet and a land army.

[43] Mardonius' establishment of democracy here can be seen as a bid to pacify Ionia, allowing his flank to be protected as he advanced towards the Hellespont and then onto Athens and Eretria.

[43] The army then marched through Thrace, re-subjugating it, since these lands had already been added to the Persian Empire in 512 BC, during Darius's campaign against the Scythians.

[46] Despite his injury, Mardonius made sure that the Brygians were defeated and subjugated, before leading his army back to the Hellespont; the remnants of the navy also retreated to Asia.

[46] Although this campaign ended ingloriously, the land approaches to Greece had been secured, and the Greeks had no doubt been made aware of Darius's intentions for them.

[47] Perhaps reasoning that the expedition of the previous year may have made his plans for Greece obvious, and weakened the resolve of the Greek cities, Darius turned to diplomacy in 491 BC.

[64] Among other ancient sources, the poet Simonides, a near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000, while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry.

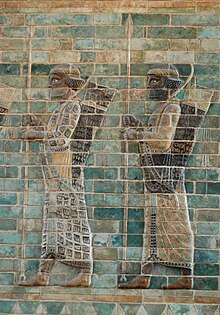

[77] The troops were, generally speaking, armed with a bow, 'short spear' and sword, carried a wicker shield, and wore at most a leather jerkin.

[85] The fleet sailed next to Naxos, in order to punish the Naxians for their resistance to the failed expedition that the Persians had mounted there a decade earlier.

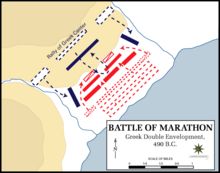

[92] Pheidippides arrived during the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and was informed that the Spartan army could not march to war until the full moon rose; Athens could not expect reinforcement for at least ten days.

[102] Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.

[107] The victory at Marathon was a defining moment for the young Athenian democracy, showing what might be achieved through unity and self-belief; indeed, the battle effectively marks the start of a 'golden age' for Athens.

[108] This was also applicable to Greece as a whole; "their victory endowed the Greeks with a faith in their destiny that was to endure for three centuries, during which western culture was born".

This style had developed during internecine warfare amongst the Greeks; since each city-state fought in the same way, the advantages and disadvantages of the hoplite phalanx had not been obvious.

[111] The phalanx formation was still vulnerable to cavalry (the cause of much caution by the Greek forces at the Battle of Plataea), but used in the right circumstances, it was now shown to be a potentially devastating weapon.

Identical depictions were made on the tombs of other Achaemenid emperors, the best preserved frieze being that of Xerxes I .