Geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics[1] is the science of measuring and representing the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of the Earth in temporally varying 3D.

Unlike a reference ellipsoid, the geoid is irregular and too complicated to serve as the computational surface for solving geometrical problems like point positioning.

The mechanical ellipticity of Earth (dynamical flattening, symbol J2) can be determined to high precision by observation of satellite orbit perturbations.

Its relationship with geometrical flattening is indirect and depends on the internal density distribution or, in simplest terms, the degree of central concentration of mass.

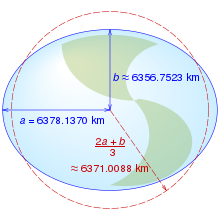

The 1980 Geodetic Reference System (GRS 80), adopted at the XVII General Assembly of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG), posited a 6,378,137 m semi-major axis and a 1:298.257 flattening.

The geoid is a "realizable" surface, meaning it can be consistently located on Earth by suitable simple measurements from physical objects like a tide gauge.

Since the advent of satellite positioning, such coordinate systems are typically geocentric, with the Z-axis aligned to Earth's (conventional or instantaneous) rotation axis.

Before the era of satellite geodesy, the coordinate systems associated with a geodetic datum attempted to be geocentric, but with the origin differing from the geocenter by hundreds of meters due to regional deviations in the direction of the plumbline (vertical).

It is easy enough to "translate" between polar and rectangular coordinates in the plane: let, as above, direction and distance be α and s respectively; then we have: The reverse transformation is given by: In geodesy, point or terrain heights are "above sea level" as an irregular, physically defined surface.

Both orthometric and normal heights are expressed in metres above sea level, whereas geopotential numbers are measures of potential energy (unit: m2 s−2) and not metric.

For normal heights, the reference surface is the so-called quasi-geoid, which has a few-metre separation from the geoid due to the density assumption in its continuation under the continental masses.

Satellite positioning receivers typically provide ellipsoidal heights unless fitted with special conversion software based on a model of the geoid.

Because coordinates and heights of geodetic points always get obtained within a system that itself was constructed based on real-world observations, geodesists introduced the concept of a "geodetic datum" (plural datums): a physical (real-world) realization of a coordinate system used for describing point locations.

In the case of height data, it suffices to choose one datum point — the reference benchmark, typically a tide gauge at the shore.

In addition, the tachymeter determines, electronically or electro-optically, the distance to a target and is highly automated or even robotic in operations.

Commonly for local detail surveys, tachymeters are employed, although the old-fashioned rectangular technique using an angle prism and steel tape is still an inexpensive alternative.

First are absolute gravimeters, based on measuring the acceleration of free fall (e.g., of a reflecting prism in a vacuum tube).

Twenty-some superconducting gravimeters are used worldwide in studying Earth's tides, rotation, interior, oceanic and atmospheric loading, as well as in verifying the Newtonian constant of gravitation.

In the future, gravity and altitude might become measurable using the special-relativistic concept of time dilation as gauged by optical clocks.

A metre was originally defined as the 10-millionth part of the length from the equator to the North Pole along the meridian through Paris (the target was not quite reached in actual implementation, as it is off by 200 ppm in the current definitions).

Various techniques are used in geodesy to study temporally changing surfaces, bodies of mass, physical fields, and dynamical systems.

Geodynamical studies require terrestrial reference frames[18] realized by the stations belonging to the Global Geodetic Observing System (GGOS[19]).