Geography of Chad

The capital city of N'Djaména, situated at the confluence of the Chari and Logone Rivers, is cosmopolitan in nature, with a current population in excess of 700,000 people.

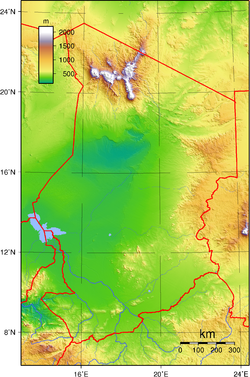

[1][2] The country's topography is generally flat,[3] with the elevation gradually rising as one moves north and east away from Lake Chad.

The Ennedi Plateau and the Ouaddaï highlands in the east complete the image of a gradually sloping basin, which descends towards Lake Chad.

The Chari and Logone Rivers, both of which originate in the Central African Republic and flow northward, provide most of the surface water entering Lake Chad.

[6] Chad's neighbors include Libya to the north, Niger and Nigeria to the west, Sudan to the east, Central African Republic to the south, and Cameroon to the southwest.

[6] Although Chadian society is economically, socially, and culturally fragmented, the country's geography is unified by the Lake Chad Basin.

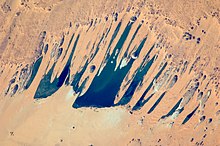

[6] This oddity arises because the great stationary dunes (ergs) of the Kanem region create a dam, preventing lake waters from flowing to the basin's lowest point.

[6] North and northeast of Lake Chad, the basin extends for more than 800 kilometers, passing through regions characterized by great rolling dunes separated by very deep depressions.

[6] Although vegetation holds the dunes in place in the Kanem region, farther north they are bare and have a fluid, rippling character.

[6] The summit of this formation—as well as the highest point in the Sahara Desert—is Emi Koussi, a dormant volcano that reaches 3,414 meters above sea level.

Southeast of Lake Chad, the regular contours of the terrain are broken by the Guéra Massif, which divides the basin into its northern and southern parts.

[6] Farther south, the basin floor slopes upward, forming a series of low sand and clay plateaus, called koros, which eventually climb to 615 meters above sea level.

[6] The most important of these streams is the Batha, which in the rainy season carries water west from the Ouaddaï Highlands and the Guéra Massif to Lake Fitri.

[6] Both river systems rise in the highlands of Central African Republic and Cameroon, regions that receive more than 1,250 millimeters of rainfall annually.

[6] At N'Djamena the Logone empties into the Chari, and the combined rivers flow together for thirty kilometers through a large delta and into Lake Chad.

[6] The Chari River contributes 95 percent of Lake Chad's water, an average annual volume of 40 billion cubic meters, 95% of which is lost to evaporation.

[6] During the rainy season, winds from the southwest push the moister maritime system north over the African continent where it meets and slips under the continental mass along a front called the "intertropical convergence zone".

[6] Much of this area receives only traces of rain during the entire year; at Faya-Largeau, for example, annual rainfall averages less than 12 millimeters (0.47 in), and there are nearly 3800 hours of sunshine.

[6] Because very few wells and springs have water throughout the year, the herders leave with the end of the rains, turning over the land to the antelopes, gazelles, and ostriches that can survive with little groundwater.

[6] In the northern Sahel, thorny shrubs and acacia trees grow wild, while date palms, cereals, and garden crops are raised in scattered oases.

[6] Outside these settlements, nomads tend their flocks during the rainy season, moving southward as forage and surface water disappear with the onset of the dry part of the year.

[6] In the southern part of the Sahel, rainfall is sufficient to permit crop production on unirrigated land, and millet and sorghum are grown.

[6] Daytime readings in Moundou, the major city in the southwest, range from 27 °C (80.6 °F) in the middle of the cool season in January to about 40 °C (104 °F) in the hot months of March, April, and May.