Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

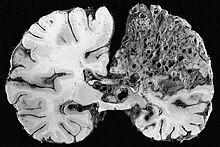

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler–Weber–Rendu disease and Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome, is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder that leads to abnormal blood vessel formation in the skin, mucous membranes, and often in organs such as the lungs, liver, and brain.

Treatment focuses on reducing bleeding from telangiectasias, and sometimes surgery or other targeted interventions to remove arteriovenous malformations in organs.

[1][2] The disease carries the names of Sir William Osler, Henri Jules Louis Marie Rendu, and Frederick Parkes Weber, who described it in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

These lesions may bleed intermittently, which is rarely significant enough to be noticed (in the form of bloody vomiting or black stool), but can eventually lead to depletion of iron in the body, resulting in iron-deficiency anemia.

[4][5] Large AVMs may lead to platypnea, difficulty in breathing that is more marked when sitting up compared to lying down; this probably reflects changes in blood flow associated with positioning.

If the connection is between arteries and veins, a large amount of blood bypasses the body's organs, for which the heart compensates by increasing the cardiac output.

[1][2] A very small proportion (those affected by SMAD4 (MADH4) mutations, see below) have multiple benign polyps in the large intestine, which may bleed or transform into colorectal cancer.

[8] People with exactly the same mutations may have different nature and severity of symptoms, suggesting that additional genes or other risk factors may determine the rate at which lesions develop; these have not yet been identified.

[2][8] Telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations in HHT are thought to arise because of changes in angiogenesis, the development of blood vessels out of existing ones.

The development of a new blood vessel requires the activation and migration of various types of cells, chiefly endothelium, smooth muscle and pericytes.

The exact mechanism by which the HHT mutations influence this process is not yet clear, and it is likely that they disrupt a balance between pro- and antiangiogenic signals in blood vessels.

[7] The skin and oral cavity telangiectasias are visually identifiable on physical examination, and similarly the lesions in the nose may be seen on endoscopy of the nasopharynx or on laryngoscopy.

Not all AVMs cause symptoms or are at risk of doing so, and hence there is a degree of variation between specialists as to whether such investigations would be performed, and by which modality; often, decisions on this issue are reached together with the patient.

[7][14] Recent professional guidelines recommend that all children with suspected or definite HHT undergo a brain MRI early in life to identify AVMs that can cause major complications.

[16] Frequent nosebleeds can be prevented in part by keeping the nostrils moist, and by applying saline solution, estrogen-containing creams or tranexamic acid; these have few side effects and may have a small degree of benefit.

However, it is highly recommended to use the least heat and time to prevent septal perforations and excessive trauma to the nasal mucosa that are already susceptible to bleeding.

This process involves injecting a small amount of an aerated irritant (detergent such as sodium tetradecyl sulfate) directly into the telangiectasias.

Intravenously administered anti-VEGF substances such as bevacizumab (brand name Avastin), pazopinab, and thalidomide or its derivatives (lenolidomide, pomalidomide) interfere with the production of new blood vessels that are weak and therefore prone to bleeding.

[17] Nevertheless, many doctors prefer alternative VEGF inhibitors; eg bevacizumab nasal spray also significantly reduces epistaxis severity without side effects.

[7] Sudden, very severe bleeding is unusual—if encountered, alternative causes (such as a peptic ulcer) need to be considered[7]—but embolization may be used in such instances.

[5][7] Those with either definite pulmonary AVMs or an abnormal contrast echocardiogram with no clearly visible lesions are deemed to be at risk from brain emboli.

They are therefore counselled to avoid scuba diving, during which small air bubbles may form in the bloodstream that may migrate to the brain and cause stroke.

Similarly, antimicrobial prophylaxis is advised during procedures in which bacteria may enter the bloodstream, such as dental work, and avoidance of air bubbles during intravenous therapy.

[2][5][7] Given that liver AVMs generally cause high-output cardiac failure, the emphasis is on treating this with diuretics to reduce the circulating blood volume, restriction of salt and fluid intake, and antiarrhythmic agents in case of irregular heart beat.

[5][6][7] Other liver-related complications (portal hypertension, esophageal varices, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy) are treated with the same modalities as used in cirrhosis, although the use of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt treatment is discouraged due to the lack of documented benefit.

The bleeding risk is predicted by previous episodes of hemorrhage, and whether on the CTA or MRA scan the AVM appears to be deep-seated or have deep venous drainage.

In a large clinical trial, bevacizumab infusion was associated with a decrease in cardiac output and reduced duration and number of episodes of epistaxis in treated HHT patients.

[7] Several 19th century English physicians, starting with Henry Gawen Sutton (1836–1891)[26] and followed by Benjamin Guy Babington (1794–1866)[27] and John Wickham Legg (1843–1921),[28] described the most common features of HHT, particularly the recurrent nosebleeds and the hereditary nature of the disease.

The French physician Henri Jules Louis Marie Rendu (1844–1902) observed the skin and mucosal lesions, and distinguished the condition from hemophilia.

[29] The Canadian-born Sir William Osler (1849–1919), then at Johns Hopkins Hospital and later at Oxford University, made further contributions with a 1901 report in which he described characteristic lesions in the digestive tract.