Historiography

During the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment, historiography in the Western world was shaped and developed by figures such as Voltaire, David Hume, and Edward Gibbon, who among others set the foundations for the modern discipline.

[3] The research interests of historians change over time, and there has been a shift away from traditional diplomatic, economic, and political history toward newer approaches, especially social and cultural studies.

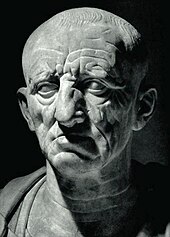

The earliest known systematic historical thought and methodologies emerged in ancient Greece and the wider Greek world, a development which would be an important influence on the writing of history elsewhere around the Mediterranean region.

Two early figures stand out: Hippias of Elis, who produced the lists of winners in the Olympic Games that provided the basic chronological framework as long as the pagan classical tradition lasted, and Hellanicus of Lesbos, who compiled more than two dozen histories from civic records, all of them now lost.

Thucydides largely eliminated divine causality in his account of the war between Athens and Sparta, establishing a rationalistic element which set a precedent for subsequent Western historical writings.

3rd century BC) composed a Greek-language History of Babylonia for the Seleucid king Antiochus I, combining Hellenistic methods of historiography and Mesopotamian accounts to form a unique composite.

[19] An example of this type of writing is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was the work of several different writers: it was started during the reign of Alfred the Great in the late 9th century, but one copy was still being updated in 1154.

[28] Islamic historical writing eventually culminated in the works of the Arab Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), who published his historiographical studies in the Muqaddimah (translated as Prolegomena) and Kitab al-I'bar (Book of Advice).

Not only did he reject traditional biographies and accounts that claim the work of supernatural forces, but he went so far as to suggest that earlier historiography was rife with falsified evidence and required new investigations at the source.

[48] Peter Gay says Voltaire wrote "very good history", citing his "scrupulous concern for truths", "careful sifting of evidence", "intelligent selection of what is important", "keen sense of drama", and "grasp of the fact that a whole civilization is a unit of study".

He said, "I have always endeavoured to draw from the fountain-head; that my curiosity, as well as a sense of duty, has always urged me to study the originals; and that, if they have sometimes eluded my search, I have carefully marked the secondary evidence, on whose faith a passage or a fact were reduced to depend.

"[56] In this insistence upon the importance of primary sources, Gibbon broke new ground in the methodical study of history: In accuracy, thoroughness, lucidity, and comprehensive grasp of a vast subject, the 'History' is unsurpassable.

According to 20th-century historian Richard Hofstadter:[58]The historians of the nineteenth century worked under the pressure of two internal tensions: on one side there was the constant demand of society—whether through the nationstate, the church, or some special group or class interest—for memory mixed with myth, for the historical tale that would strengthen group loyalties or confirm national pride; and against this there were the demands of critical method, and even, after a time, the goal of writing "scientific" history.Thomas Carlyle published his three-volume The French Revolution: A History, in 1837.

His inquiry into manuscript and printed authorities was most laborious, but his lively imagination, and his strong religious and political prejudices, made him regard all things from a singularly personal point of view.

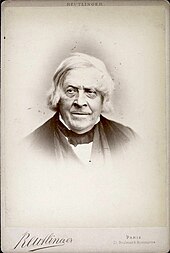

[64]Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893), although unable to secure an academic position, was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism, and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism.

[66] Siegfried Giedion described Burckhardt's achievement in the following terms: "The great discoverer of the age of the Renaissance, he first showed how a period should be treated in its entirety, with regard not only for its painting, sculpture and architecture, but for the social institutions of its daily life as well.

Beginning with his first book in 1824, the History of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples from 1494 to 1514, Ranke used an unusually wide variety of sources for a historian of the age, including "memoirs, diaries, personal and formal missives, government documents, diplomatic dispatches and first-hand accounts of eye-witnesses".

Over a career that spanned much of the century, Ranke set the standards for much of later historical writing, introducing such ideas as reliance on primary sources, an emphasis on narrative history and especially international politics (Aussenpolitik).

"[76] This realization is seen by studying the various cultures that have developed over the millennia, and trying to understand the way that freedom has worked itself out through them: World history is the record of the spirit's efforts to attain knowledge of what it is in itself.

His writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with freedom of belief and expression.

An eminent member of this school, Georges Duby, described his approach to history as one that relegated the sensational to the sidelines and was reluctant to give a simple accounting of events, but strived on the contrary to pose and solve problems and, neglecting surface disturbances, to observe the long and medium-term evolution of economy, society and civilisation.

The Annales historians, after living through two world wars and major political upheavals in France, were deeply uncomfortable with the notion that multiple ruptures and discontinuities created history.

He was profoundly interested in the issue of the enclosure of land in the English countryside in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and in Max Weber's thesis on the connection between the appearance of Protestantism and the rise of capitalism.

While some members of the group (most notably Christopher Hill and E. P. Thompson) left the CPGB after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the common points of British Marxist historiography continued in their works.

In his preface to this book, Thompson set out his approach to writing history from below: I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the "obsolete" hand-loom weaver, the "Utopian" artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity.

[4] The growth was enabled by the social sciences, computers, statistics, new data sources such as individual census information, and summer training programs at the Newberry Library and the University of Michigan.

[157][158]: 212 This movement towards utilising oral sources in a multi-disciplinary approach culminated in UNESCO commissioning the General History of Africa, edited by specialists drawn from across the African continent, and publishing from 1981 to 2024.

The malleability of culture suggest to me that in order to understand its effect on policy, one needs also to study the dynamics of political economy, the evolution of the international system, and the roles of technology and communication, among many other variables.

Stone defined narrative as follows: it is organized chronologically; it is focused on a single coherent story; it is descriptive rather than analytical; it is concerned with people not abstract circumstances; and it deals with the particular and specific rather than the collective and statistical.

"[188] Historians committed to a social science approach, however, have criticized the narrowness of narrative and its preference for anecdote over analysis, and its use of clever examples rather than statistically verified empirical regularities.