History of Antarctica

[1] Accounts name the area "Te tai-uka-a-pia", which literally means 'powdered pia', but in some interpretations it may refer to snow or ice due to the lack of a word for these phenomena in Polynesian languages.

[2][1][3] However, this interpretation of the original account is disputed by Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Henry Buck) who lists evidence for his belief that 'later historians embellished the tales by adding details learned from European whalers and teachers'.

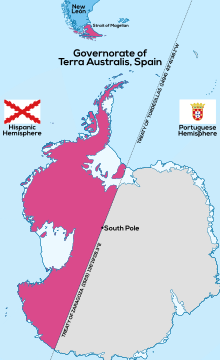

[8] In 1473, Portuguese navigator Lopes Gonçalves proved that the equator could be crossed, and cartographers and sailors began to assume the existence of another, temperate continent to the south of the known world.

European geographers connected the coast of Tierra del Fuego with the coast of New Guinea on their globes, and allowing their imaginations to run riot in the vast unknown spaces of the south Atlantic, south Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean, they sketched the outlines of the Terra Australis Incognita ("Unknown Southern Land"), a vast continent stretching in parts into the tropics.

Before the construction of the Panama Canal, the passages around Tierra del Fuego, notorious for their harsh weather, served as the primary route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Voyagers round the Horn frequently met with contrary winds and were driven southward into snowy skies and ice-encumbered seas; but, so far as can be ascertained, none of them before 1770 reached the Antarctic Circle, or knew it, if they did.

[8] The Dutch expedition to Valdivia of 1643 intended to round Cape Horn sailing through Le Maire Strait but strong winds made it instead drift south and east.

[14] The small fleet led by Hendrik Brouwer managed to enter the Pacific Ocean sailing south of Isla de los Estados disproving earlier beliefs that it was part of Terra Australis.

[8] The obsession of the undiscovered continent culminated in the brain of Alexander Dalrymple, the brilliant and erratic hydrographer who was nominated by the Royal Society to command the Transit of Venus expedition to Tahiti in 1769.

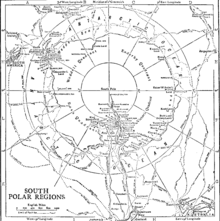

He turned south again and was stopped by ice in 61° 52′ S by 95° E and continued eastward nearly on the parallel of 60° S to 147° E. On 16 March, the approaching winter drove him northward for rest to New Zealand and the tropical islands of the Pacific.

The Antarctic Circle was crossed on 20 December and Cook remained south of it for three days, being compelled after reaching 67° 31′ S to stand north again in 135° W.[8] A long detour to 47° 50′ S served to show that there was no land connection between New Zealand and Tierra del Fuego.

On reaching Valparaiso, Smith reported his discovery of the islands and the abundance of seals there, to Captain William Henry Shirreff, of HMS Andromache,[20] which had arrived there about 5 September 1818.

At the beginning of the following year, 1820, the Royal Navy chartered Williams and dispatched with her with Lieutenant Edward Bransfield on board to survey the newly discovered islands and formally claim them for Great Britain, because Smith was a civilian and his October declaration had no legal force.

A piece of wood, from the South Shetland Islands, was the first fossil ever recorded from Antarctica, obtained during a private United States expedition during 1829–31, commanded by Captain Benjamin Pendleton.

At the turn of February and March 1838 the expedition was already in Bransfield Strait, where it had mapped part of the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, which it named the Louis Philippe Land.

[b][48] In the late 19th century, New Zealand anthropologist Percy Smith proposed a theory about a Polynesian explorer named Ui-te-Rangiora, who may have reached Antarctica or subantarctic islands.

[56] Furthermore, the Royal Geographical Society instated an Antarctic Committee shortly prior to this, in 1887, which successfully encouraged many whalers to explore the Southern regions of the world and laid the groundwork for the lecture given by Murray.

[58] In August 1895 the Sixth International Geographical Congress in London passed a general resolution calling on scientific societies throughout the world to promote the cause of Antarctic exploration "in whatever ways seem to them most effective".

Two expeditions set off in 1910 to attain this goal; a party led by Norwegian Polar explorer Roald Amundsen from the ship Fram and Robert Falcon Scott's British group from the Terra Nova.

After spending the winter of 1957 at Shackleton Base, Fuchs finally set out on the transcontinental journey in November 1957, with a twelve-man team travelling in six vehicles; three Sno-Cats, two Weasels and one specially adapted Muskeg tractor.

In parallel Hillary's team had set up Scott Base – which was to be Fuchs' final destination – on the opposite side of the continent at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea.

Using three converted Ferguson TE20 tractors[101] and one M29 Weasel (abandoned part-way), Hillary and his three men (Ron Balham, Peter Mulgrew and Murray Ellis), were responsible for route-finding and laying a line of supply depots up the Skelton Glacier and across the Polar Plateau on towards the South Pole, for the use of Fuchs on the final leg of his journey.

In a memorandum to the governor-generals for Australia and New Zealand, he wrote that 'with the exception of Chile and Argentina and some barren islands belonging to France... it is desirable that the whole of the Antarctic should ultimately be included in the British Empire.'

The whale-ship owner Lars Christensen financed several expeditions to the Antarctic with the view to claim land for Norway and establish stations on Norwegian territory to gain better privileges.

Already in 1904 the Argentine government began a permanent occupation in the area with the purchase of a meteorological station on Laurie Island established in 1903 by Dr William S. Bruce's Scottish National Antarctic Expedition.

The Chilean commission set the bounds according to the Theory of polar areas, taking into account geographical, historical, legal, and diplomatic precedents, which were formalized by Decree No.

Also, in 1941, there existed a fear that Japan might attempt to seize the Falkland Islands, either as a base or to hand them over to Argentina, thus gaining political advantage for the Axis and denying their use to Britain.

The expedition was led by Lieutenant James Marr and left the Falkland Islands in two ships, HMS William Scoresby (a minesweeping trawler) and Fitzroy, on Saturday 29 January 1944.

The mission was also aimed at consolidating and extending United States sovereignty over the largest practicable area of the Antarctic continent, although this was publicly denied as a goal even before the expedition ended.

Negotiations towards the establishment of an international condominium over the continent first began in 1948, involving the 7 claimant powers (Britain, Australia, New Zealand, France, Norway, Chile and Argentina) and the US.