History of New Spain

The eventual alliance between royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide and insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero led to the successful campaign for independence.

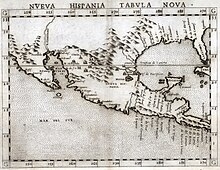

The Caribbean islands and early Spanish explorations around the circum-Caribbean region had not been of major political, strategic, or financial importance until the conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521.

However, important precedents of exploration, conquest, and settlement and crown rule had been initially worked out in the Caribbean, which long affected subsequent regions, including Mexico and Peru.

In addition to the Church's explicit political role, the Catholic faith became a central part of Spanish identity after the conquest of last Muslim kingdom in the peninsula, the Emirate of Granada, and the expulsion of all Jews who did not convert to Catholicism.

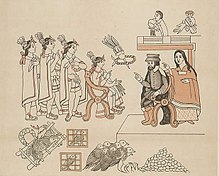

As a result, a second wave of missionaries began an effort to completely erase the old beliefs, which they associated with the ritualized human sacrifice found in many of the native religions.

Upon his arrival, Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza vigorously took to the duties entrusted to him by the king and encouraged the exploration of Spain's new mainland territories.

However, due to the higher quantity of products from Asia it became a point of contention with the mercantilist policies of mainland Spain which supported manufacturing based on the capital instead of the colonies, in which case the Manila-Mexico commercial alliance was at odds against Madrid.

There was thus high desertion and death rates which also applied to the native Filipino warriors and laborers levied by Spain, to fight in battles all across the archipelago and elsewhere or build galleons and public works.

The repeated wars, lack of wages, dislocation, and near starvation were so intense, that almost half of the soldiers sent from Latin America and the warriors and laborers recruited locally either died or disbanded to the lawless countryside to live as vagabonds among the rebellious natives, escaped enslaved Indians (from India)[27] and Negrito nomads, where they race-mixed through rape or prostitution, which increased the number of Filipinos of Spanish or Latin American descent, but were not the children of valid marriages.

Due to these, the Royal Fiscal of Manila wrote a letter to King Charles III of Spain, in which he advises to abandon the colony, but this was successfully opposed by the religious and missionary orders that argued that the Philippines was a launching pad for further conversions in the Far East.

At times, non-profitable war-torn Philippine colony survived on an annual subsidy paid by the Spanish Crown and often procured from taxes and profits accumulated by the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico), mainly paid by annually sending 75 tons of precious Silver Bullion,[31] gathered from and mined from Potosi, Bolivia where hundreds of thousands of Incan lives were regularly lost while being enslaved to the Mit'a system.

[32] Unfortunately, the silver mined through the cost of many lives and being a precious metal barely made it to the starving or dying Spanish, Mexican, Peruvian and Filipino soldiers who were stationed in presidios across the archipelago, struggling against constant invasions, while it was sought after by Chinese, Indian, Arab and Malay merchants in Manila who traded with the Latinos for their precious metal in exchange for silk, spices, pearls and aromatics.

[clarification needed] The idealistic original pioneers died and were replaced by ignorant royal officers who broke treaties, thus causing the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas among Filipinos, who conspired together with Bruneians and Japanese, yet the failure of the conspiracy caused the royals' exile to the Americas, where they formed communities across the western coasts, chief among which was Guerrero, Mexico,[33] which was later a center of the Mexican war of Independence.

The Chichimeca war lasted over fifty years, 1550–1606, between the Spanish and various indigenous groups of northern New Spain, particularly in silver mining regions and the transportation trunk lines.

[39][40] The British capture and occupation of both Manila and Havana in 1762, during the global conflict of the Seven Years' War, meant that the Spanish crown had to rethink its military strategy for defending its possessions.

The crown strengthened the defenses of Veracruz and San Juan de Ulúa, Jamaica, Cuba, and Florida, but the British sacked ports in the late seventeenth century.

Santiago de Cuba (1662), St. Augustine Spanish Florida (1665) and Campeche 1678 and so with the loss of Havana and Manila, Spain realized it needed to take significant steps.

The Bourbons sought a return to the monarchical ideal of having those not directly connected with local elites as administrators, who in theory should be disinterested, staff the higher echelons of regional government.

In practice this meant that there was a concerted effort to appoint mostly peninsulares, usually military men with long records of service, as opposed to the Habsburg preference for prelates, who were willing to move around the global empire.

The intendancies were one new office that could be staffed with peninsulares, but throughout the 18th century significant gains were made in the numbers of governors-captain generals, audiencia judges and bishops, in addition to other posts, who were Spanish-born.

Croix closed the religious autos-de-fe of the Holy Office of the Inquisition to public viewing, signaling a shift in the crown's attitude toward religion.

Other significant accomplishments under Croix's administration was the founding of the College of Surgery in 1768, part of the crown's push to introduce institutional reforms that regulated professions.

Bucareli was opposed to Gálvez's plan to implement the new administrative organization of intendancies, which he believed would burden areas with sparse population with excessive costs for the new bureaucracy.

They were first introduced on a large scale in New Spain, by the Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez, in the 1770s, who originally envisioned that they would replace the viceregal system (viceroyalty) altogether.

The creation of a military meant that some American Spaniards became officers in local militias, but the ranks were filled with poor, mixed-race men, who resented service and avoided it if possible.

Although this episode is largely forgotten, it ended in a decisive victory for Spain, who managed to prolong its control of the Caribbean and indeed secure the Spanish Main until the 19th century.

Galvez's army engaged and defeated the British in battles fought at Manchac and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Natchez, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida.

New Spain claimed the entire west coast of North America and therefore considered the Russian fur trading activity in Alaska, which began in the middle to late 18th century, an encroachment and threat.

[49] In 1789, at Santa Cruz de Nuca, a conflict occurred between the Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez and the British merchant James Colnett, triggering the Nootka Crisis, which grew into an international incident and the threat of war between Britain and Spain.

Royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide proposed uniting with the insurgents with whom he had battled, and gained the alliance of Vicente Guerrero, leader of the insurgents in a region now bearing his name, a region that was populated by immigrants from Africa and the Philippines,[50][51] crucial among which was the Filipino-Mexican General Isidoro Montes de Oca who impressed Criollo Royalist Itubide into joining forces with Vicente Guerrero by Isidoro Montes De Oca defeating royalist forces three times larger than his, in the name of his leader, Vicente Guerrero.