Ice age

In 1815 the carpenter and chamois hunter Jean-Pierre Perraudin (1767–1858) explained erratic boulders in the Val de Bagnes in the Swiss canton of Valais as being due to glaciers previously extending further.

[11] An unknown woodcutter from Meiringen in the Bernese Oberland advocated a similar idea in a discussion with the Swiss-German geologist Jean de Charpentier (1786–1855) in 1834.

When the Bavarian naturalist Ernst von Bibra (1806–1878) visited the Chilean Andes in 1849–1850, the natives attributed fossil moraines to the former action of glaciers.

The Swedish mining expert Daniel Tilas (1712–1772) was, in 1742, the first person to suggest drifting sea ice was a cause of the presence of erratic boulders in the Scandinavian and Baltic regions.

At the University of Edinburgh Robert Jameson (1774–1854) seemed to be relatively open to Esmark's ideas, as reviewed by Norwegian professor of glaciology Bjørn G. Andersen (1992).

[24] In Germany, Albrecht Reinhard Bernhardi (1797–1849), a geologist and professor of forestry at an academy in Dreissigacker (since incorporated in the southern Thuringian city of Meiningen), adopted Esmark's theory.

[25] In Val de Bagnes, a valley in the Swiss Alps, there was a long-held local belief that the valley had once been covered deep in ice, and in 1815 a local chamois hunter called Jean-Pierre Perraudin attempted to convert the geologist Jean de Charpentier to the idea, pointing to deep striations in the rocks and giant erratic boulders as evidence.

[27] Schimper spent the summer months of 1836 at Devens, near Bex, in the Swiss Alps with his former university friend Louis Agassiz (1801–1873) and Jean de Charpentier.

This happened on an international scale in the second half of the 1870s, following the work of James Croll, including the publication of Climate and Time, in Their Geological Relations in 1875, which provided a credible explanation for the causes of ice ages.

Marie to Sudbury, northeast of Lake Huron, with giant layers of now-lithified till beds, dropstones, varves, outwash, and scoured basement rocks.

Although the Mesozoic Era retained a greenhouse climate over its timespan and was previously assumed to have been entirely glaciation-free, more recent studies suggest that brief periods of glaciation occurred in both hemispheres during the Early Cretaceous.

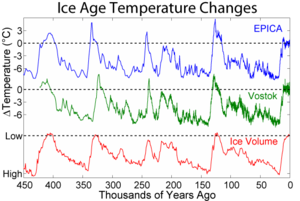

[51] Glacials are characterized by cooler and drier climates over most of Earth and large land and sea ice masses extending outward from the poles.

This allows winds to transport iron rich dust into the open ocean, where it acts as a fertilizer that causes massive algal blooms that pulls large amounts of CO2 out of the atmosphere.

When low-temperature ice covers the Arctic Ocean there is little evaporation or sublimation and the polar regions are quite dry in terms of precipitation, comparable to the amount found in mid-latitude deserts.

With higher precipitation, portions of this snow may not melt during the summer and so glacial ice can form at lower altitudes and more southerly latitudes, reducing the temperatures over land by increased albedo as noted above.

The consensus is that several factors are important: atmospheric composition, such as the concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane (the specific levels of the previously mentioned gases are now able to be seen with the new ice core samples from the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) Dome C in Antarctica over the past 800,000 years); changes in Earth's orbit around the Sun known as Milankovitch cycles; the motion of tectonic plates resulting in changes in the relative location and amount of continental and oceanic crust on Earth's surface, which affect wind and ocean currents; variations in solar output; the orbital dynamics of the Earth–Moon system; the impact of relatively large meteorites and volcanism including eruptions of supervolcanoes.

Maureen Raymo, William Ruddiman and others propose that the Tibetan and Colorado Plateaus are immense CO2 "scrubbers" with a capacity to remove enough CO2 from the global atmosphere to be a significant causal factor of the 40 million year Cenozoic Cooling trend.

Some scientists believe that the Himalayas are a major factor in the current ice age, because these mountains have increased Earth's total rainfall and therefore the rate at which carbon dioxide is washed out of the atmosphere, decreasing the greenhouse effect.

Another important contribution to ancient climate regimes is the variation of ocean currents, which are modified by continent position, sea levels and salinity, as well as other factors.

The closing of the Isthmus of Panama about 3 million years ago may have ushered in the present period of strong glaciation over North America by ending the exchange of water between the tropical Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

[69] According to a study published in Nature in 2021, all glacial periods of ice ages over the last 1.5 million years were associated with northward shifts of melting Antarctic icebergs which changed ocean circulation patterns, leading to more CO2 being pulled out of the atmosphere.

According to Kuhle, the plate-tectonic uplift of Tibet past the snow-line has led to a surface of c. 2,400,000 square kilometres (930,000 sq mi) changing from bare land to ice with a 70% greater albedo.

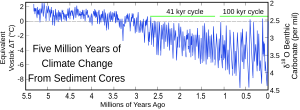

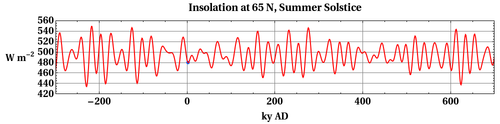

While Milankovitch forcing predicts that cyclic changes in Earth's orbital elements can be expressed in the glaciation record, additional explanations are necessary to explain which cycles are observed to be most important in the timing of glacial–interglacial periods.

The reasons for dominance of one frequency versus another are poorly understood and an active area of current research, but the answer probably relates to some form of resonance in Earth's climate system.

[86] One suggested explanation of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum is that undersea volcanoes released methane from clathrates and thus caused a large and rapid increase in the greenhouse effect.

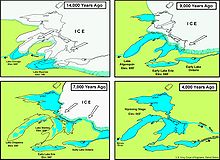

The area from Long Island to Nantucket, Massachusetts was formed from glacial till, and the plethora of lakes on the Canadian Shield in northern Canada can be almost entirely attributed to the action of the ice.

As the ice retreated and the rock dust dried, winds carried the material hundreds of miles, forming beds of loess many dozens of feet thick in the Missouri Valley.

[96][97] Where current glaciers scarcely reach 10 km in length, the snowline (ELA) runs at a height of 4,600 m and at that time was lowered to 3,200 m asl, i.e. about 1,400 m. From this follows that—beside of an annual depression of temperature about c. 8.4 °C— here was an increase in precipitation.

The erratic boulders, till, drumlins, eskers, fjords, kettle lakes, moraines, cirques, horns, etc., are typical features left behind by the glaciers.

[5] Hypothetical runaway greenhouse state Tropical temperatures may reach poles Global climate during an ice age Earth's surface entirely or nearly frozen over