Epigraphy

Individual contributions have been made by epigraphers such as Georg Fabricius (1516–1571); Stefano Antonio Morcelli (1737–1822); Luigi Gaetano Marini (1742–1815); August Wilhelm Zumpt (1815–1877); Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903); Emil Hübner (1834–1901); Franz Cumont (1868–1947); Louis Robert (1904–1985).

Specialists depend on such on-going series of volumes in which newly discovered inscriptions are published, often in Latin, not unlike the biologists' Zoological Record – the raw material of history.

The second, modern corpus is Inscriptiones Graecae arranged geographically under categories: decrees, catalogues, honorary titles, funeral inscriptions, various, all presented in Latin, to preserve the international neutrality of the field of classics.

Here an inscription of great length is incised on the slabs of a theatre-shaped structure in 12 columns of 50 lines each; it is mainly concerned with the law of inheritance, adoption, etc.

A bronze tablet records in some detail the arrangements of this sort made when Locrians established a colony in Naupactus; another inscription relates to the Athenian colonisation of Salamis, in the 6th century BC.

Those of Athens are by far the most exactly known, owing to the immense number that have been discovered; and they are so strictly stereotyped that can be classified with the precision of algebraic formulae, and often dated to within a few years by this test alone.

It was customary to inscribe on stone all records of the receipt, custody and expenditure of public money or treasure, so that citizens could verify for themselves the safety and due control of the State in all financial matters.

[10] In the case of the Erechtheum, we have not only a detailed report on the unfinished state of the building in 409 BC, but also accounts of the expenditure and payments to the workmen employed in finishing it.

[11][12] Naval and military expenditure is also fully accounted for; among other information there are records of the galley-slips at the different harbours of the Piraeus, and of the ships of the Athenian navy, with their names and condition.

It is possible to trace in the inscriptions, which range over several centuries, how what was originally a system of physical and military training for Athenian youths from age of 18 to 20, with outpost and police duties, was gradually transformed.

These were incised on bronze or stone, and set up in places of public resort in the cities concerned, or in common religious centres such as Olympia and Delphi.

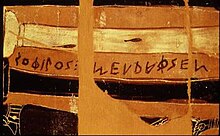

These have been made the basis of a minute historical and stylistic study of the work of these painters, and unsigned vases also have been grouped with the signed ones, so as to make an exact and detailed record of this branch of Greek artistic production.

The most famous historical record is the autobiographical account of the deeds and administration of Augustus, which was reproduced and set up in many places; it is generally known as the Monumentum Ancyranum, because the most complete copy of it was found at Ancyra.

The Marmor Parium at Oxford, found in Paros, is a chronological record of Greek history, probably made for educational purposes, and valuable as giving the traditional dates of events from the earliest time down.

These are of great number and variety, and while some of them can be easily interpreted as belonging to well-known formulae, others offer considerable difficulty, especially to the inexperienced student.

The commonest materials in this case also are stone, marble and bronze; but a more extensive use is made of stamped bricks and tiles, which are often of historical value as identifying and dating a building or other construction.

Inscriptions are also found on sling bullets – Roman as well as Greek; there are also numerous classes of tesserae or tickets of admission to theatres or other shows.

Some were regarded as offices of high distinction and were open only to men of senatorial rank; among these were the Augurs, the Fetiales, the Salii; also the Sodales Divorum Augustorum in imperial times.

One of the earliest relates to the prohibition of bacchanalian orgies in Italy; it takes the form of a message from the magistrates, stating the authority on which they acted.

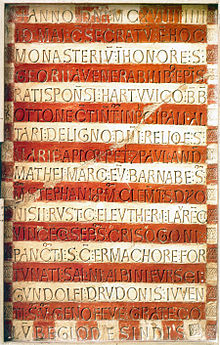

[21] A very large number of inscriptions record the construction or repair of public buildings by private individuals, by magistrates, Roman or provincial, and by emperors.

In addition to the dedication of temples, we find inscriptions recording the construction of aqueducts, roads, especially on milestones, baths, basilicas, porticos and many other works of public utility.

"They are numerous and of all sorts – tombstones of every degree, lists of soldiers' burial clubs, certificates of discharge from service, schedules of time-expired men, dedications of altars, records of building or of engineering works accomplished.

"[22] But when the information from hundreds of such inscriptions is collected together, "you can trace the whole policy of the Imperial Government in the matter of recruiting, to what extent and till what date legionaries were raised in Italy; what contingents for various branches of the service were drawn from the provinces, and which provinces provided most; how far provincials garrisoned their own countries, and which of them, like the British recruits, were sent as a measure of precaution to serve elsewhere; or, finally, at what epoch the empire grew weak enough to require the enlistment of barbarians from beyond its frontiers.

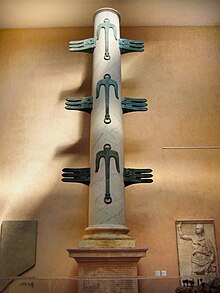

Among the most interesting is the inscription of the Columna Rostrata in Rome, which records the great naval victory of Gaius Duilius over the Carthaginians; this, however, is not the original, but a later and somewhat modified version.

These are probably the most numerous of all classes of inscriptions; and though many of them are of no great individual interest, they convey, when taken collectively, much valuable information as to the distribution and transference of population, as to trades and professions, as to health and longevity, and as to many other conditions of ancient life.

The most interesting early series is that on the tombs of the Scipios at Rome, recording, mostly in Saturnian Metre, the exploits and distinctions of the various members of that family.

Early inscriptions, such as those from the 1st century BCE in Ayodhya and Hathibada, are written in Brahmi script and reflect the transition to classical Sanskrit.

[25][26] The turning point in Sanskrit epigraphy came with the Rudradaman I inscription from the mid-2nd century CE, which established a poetic eulogy style later adopted during the Gupta Empire.

This era saw Sanskrit become the predominant language for royal and religious records, documenting donations, public works, and the glorification of rulers.

In South India, inscriptions such as those from Nagarjunakonda and Amaravati illustrate early use in Buddhist and Shaivite contexts, transitioning to exclusive Sanskrit use from the 4th century CE.