Antoine Lavoisier

The Ferme générale was one of the most hated components of the Ancien Régime because of the profits it took at the expense of the state, the secrecy of the terms of its contracts, and the violence of its armed agents.

At the height of the French Revolution, he was charged with tax fraud and selling adulterated tobacco, and was guillotined despite appeals to spare his life in recognition of his contributions to science.

In 1764 he read his first paper to the French Academy of Sciences, France's most elite scientific society, on the chemical and physical properties of gypsum (hydrated calcium sulfate), and in 1766 he was awarded a gold medal by the King for an essay on the problems of urban street lighting.

On behalf of the Ferme générale Lavoisier commissioned the building of a wall around Paris so that customs duties could be collected from those transporting goods into and out of the city.

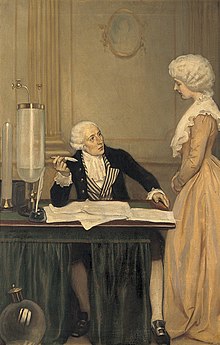

Lavoisier consolidated his social and economic position when, in 1771 at age 28, he married Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, the 13-year-old daughter of a senior member of the Ferme générale.

[4] She was to play an important part in Lavoisier's scientific career—notably, she translated English documents for him, including Richard Kirwan's Essay on Phlogiston and Joseph Priestley's research.

Completed in 1788 on the eve of the Revolution, the painting was denied a customary public display at the Paris Salon for fear that it might inflame anti-aristocratic passions.

Lavoisier also found that while adding a lot of water to bulk the tobacco up would cause it to ferment and smell bad, the addition of a very small amount improved the product.

[20] To ensure that only these authorised amounts were added, and to exclude the black market, Lavoisier saw to it that a watertight system of checks, accounts, supervision and testing made it very difficult for retailers to source contraband tobacco or to improve their profits by bulking it up.

He then served as its Secretary and spent considerable sums of his own money in order to improve the agricultural yields in the Sologne, an area where farmland was of poor quality.

In 1788 Lavoisier presented a report to the Commission detailing ten years of efforts on his experimental farm to introduce new crops and types of livestock.

His conclusion was that despite the possibilities of agricultural reforms, the tax system left tenant farmers with so little that it was unrealistic to expect them to change their traditional practices.

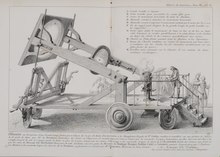

In 1775 he was made one of four commissioners of gunpowder appointed to replace a private company, similar to the Ferme Générale, which had proved unsatisfactory in supplying France with its munitions requirements.

He also intervened on behalf of a number of foreign-born scientists including mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange, helping to exempt them from a mandate stripping all foreigners of possessions and freedom.

Lavoisier drafted their defense, refuting the financial accusations, reminding the court of how they had maintained a consistently high quality of tobacco.

[36] An apocryphal[37] story exists regarding Lavoisier's execution in which the scientist blinked his eyes to demonstrate that the head retained some consciousness after being severed.

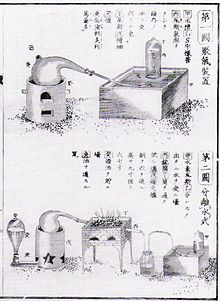

In a second sealed note deposited with the academy a few weeks later (1 November) Lavoisier extended his observations and conclusions to the burning of sulfur and went on to add that "what is observed in the combustion of sulfur and phosphorus may well take place in the case of all substances that gain in weight by combustion and calcination: and I am persuaded that the increase in weight of metallic calces is due to the same cause.

In the course of this review, he made his first full study of the work of Joseph Black, the Scottish chemist who had carried out a series of classic quantitative experiments on the mild and caustic alkalies.

[citation needed] In the spring of 1774, Lavoisier carried out experiments on the calcination of tin and lead in sealed vessels, the results of which conclusively confirmed that the increase in weight of metals in combustion was due to combination with air.

In October the English chemist Joseph Priestley visited Paris, where he met Lavoisier and told him of the air which he had produced by heating the red calx of mercury with a burning glass and which had supported combustion with extreme vigor.

He carefully weighed the reactants and products of a chemical reaction in a sealed glass vessel so that no gases could escape, which was a crucial step in the advancement of chemistry.

His introduction of new terminology, a binomial system modeled after that of Linnaeus, also helps to mark the dramatic changes in the field which are referred to generally as the chemical revolution.

Joseph Priestley, Richard Kirwan, James Keir, and William Nicholson, among others, argued that quantification of substances did not imply conservation of mass.

That year Lavoisier also began a series of experiments on the composition of water which were to prove an important capstone to his combustion theory and win many converts to it.

All of the researchers noted Cavendish's production of pure water by burning hydrogen in oxygen, but they interpreted the reaction in varying ways within the framework of phlogiston theory.

Lavoisier learned of Cavendish's experiment in June 1783 via Charles Blagden (before the results were published in 1784), and immediately recognized water as the oxide of a "hydrogenerative" gas.

[46] Opposition responded to this further experimentation by stating that Lavoisier continued to draw the incorrect conclusions and that his experiment demonstrated the displacement of phlogiston from iron by the combination of water with the metal.

It presented a unified view of new theories of chemistry, contained a clear statement of the law of conservation of mass, and denied the existence of phlogiston.

While many leading chemists of the time refused to accept Lavoisier's new ideas, demand for Traité élémentaire as a textbook in Edinburgh was sufficient to merit translation into English within about a year of its French publication.

[56] During his lifetime, Lavoisier was awarded a gold medal by the King of France for his work on urban street lighting (1766), and was appointed to the French Academy of Sciences (1768).