Lone pair

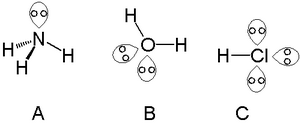

[6] A lone pair can contribute to the existence of chirality in a molecule, when three other groups attached to an atom all differ.

A stereochemically active lone pair is also expected for divalent lead and tin ions due to their formal electronic configuration of ns2.

In the solid state this results in the distorted metal coordination observed in the tetragonal litharge structure adopted by both PbO and SnO.

[9] This dependence on the electronic states of the anion can explain why some divalent lead and tin materials such as PbS and SnTe show no stereochemical evidence of the lone pair and adopt the symmetric rocksalt crystal structure.

[10][11] In molecular systems the lone pair can also result in a distortion in the coordination of ligands around the metal ion.

This inhibition of heme synthesis appears to be the molecular basis of lead poisoning (also called "saturnism" or "plumbism").

In the organogermanium compound (Scheme 1 in the reference), the effective bond order is also 1, with complexation of the acidic isonitrile (or isocyanide) C-N groups, based on interaction with germanium's empty 4p orbital.

In more advanced courses, an alternative explanation for this phenomenon considers the greater stability of orbitals with excess s character using the theory of isovalent hybridization, in which bonds and lone pairs can be constructed with spx hybrids wherein nonintegral values of x are allowed, so long as the total amount of s and p character is conserved (one s and three p orbitals in the case of second-row p-block elements).

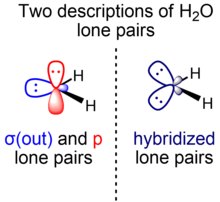

In this case, we can construct the two equivalent lone pair hybrid orbitals h and h' by taking linear combinations h = c1σ(out) + c2p and h' = c1σ(out) – c2p for an appropriate choice of coefficients c1 and c2.

For chemical and physical properties of water that depend on the overall electron distribution of the molecule, the use of h and h' is just as valid as the use of σ(out) and p. In some cases, such a view is intuitively useful.

For example, the stereoelectronic requirement for the anomeric effect can be rationalized using equivalent lone pairs, since it is the overall donation of electron density into the antibonding orbital that matters.

[21] Similarly, the hydrogen bonds of water form along the directions of the "rabbit ears" lone pairs, as a reflection of the increased availability of electrons in these regions.

[21][22] Because of the popularity of VSEPR theory, the treatment of the water lone pairs as equivalent is prevalent in introductory chemistry courses, and many practicing chemists continue to regard it as a useful model.

[23] However, the question of whether it is conceptually useful to derive equivalent orbitals from symmetry-adapted ones, from the standpoint of bonding theory and pedagogy, is still a controversial one, with recent (2014 and 2015) articles opposing[24] and supporting[25] the practice.