Manhattan Project

A team of Columbia professors including Fermi, Szilard, Eugene T. Booth and John Dunning created the first nuclear fission reaction in the Americas, verifying the work of Hahn and Strassmann.

He created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself—although he never attended a meeting—Wallace, Bush, Conant, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, and the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George C. Marshall.

[23] Arthur Compton asked theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer of the University of California to take over research into fast neutron calculations—key to calculations of critical mass and weapon detonation—from Gregory Breit, who had quit on 18 May 1942 because of concerns over lax operational security.

[28] To review this work and the general theory of fission reactions, Oppenheimer and Fermi convened meetings at the University of Chicago in June and at the University of California in July 1942 with theoretical physicists Hans Bethe, John Van Vleck, Edward Teller, Emil Konopinski, Robert Serber, Stan Frankel, and Eldred C. (Carlyle) Nelson, and experimental physicists Emilio Segrè, Felix Bloch, Franco Rasetti, Manley, and Edwin McMillan.

[30] They also explored designs involving spheroids, a primitive form of "implosion" suggested by Richard C. Tolman, and the possibility of autocatalytic methods to increase the efficiency of the bomb as it exploded.

Marshall created a liaison office in Washington, D.C., but established his temporary headquarters at 270 Broadway in New York, where he could draw on administrative support from the Corps of Engineers' North Atlantic Division.

[79][80] On 29 September 1942, United States Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson authorized the Corps of Engineers to acquire 56,000 acres (23,000 ha) of land by eminent domain at a cost of $3.5 million.

[96] Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard granted about 45,000 acres (18,000 ha) of United States Forest Service land to the War Department "for so long as the military necessity continues".

In July, Nichols arranged for a lease of 1,025 acres (415 ha) from the Cook County Forest Preserve District, and Captain James F. Grafton was appointed Chicago area engineer.

[103][104] Delays in establishing the plant at Site A led Arthur Compton to authorize the Metallurgical Laboratory to construct the first nuclear reactor beneath the bleachers of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago.

"[109][e] In January 1943, Grafton's successor, Major Arthur V. Peterson, ordered Chicago Pile-1 dismantled and reassembled at the Site A in the forest preserve, as he regarded the operation of a reactor as too hazardous for a densely populated area.

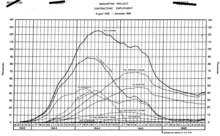

Although progress on the reactor design at Metallurgical Laboratory and DuPont was not sufficiently advanced to accurately predict the scope of the project, a start was made in April 1943 on facilities for an estimated 25,000 workers, half of whom were expected to live on-site.

[119] Like Los Alamos and Oak Ridge, Richland was a gated community with restricted access, but it looked more like a typical wartime American boomtown: the military profile was lower, and physical security elements like high fences and guard dogs were less evident.

The prospect of keeping so many rotors operating continuously at high speed appeared daunting,[144] and when Beams ran his experimental apparatus, he obtained only 60% of the predicted yield, indicating that more centrifuges were required.

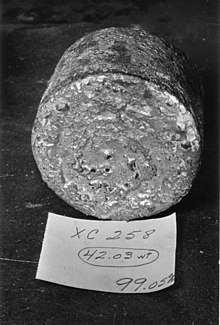

They were pickled to remove dirt and impurities, dipped in molten bronze, tin, and aluminum-silicon alloy, canned using hydraulic presses, and then capped using arc welding under an argon atmosphere.

The scientists had originally considered this overengineering a waste of time and money, but Fermi realized that by loading all 2,004 tubes, the reactor could reach the required power level and efficiently produce plutonium.

Working with the minute quantities of plutonium available at the Metallurgical Laboratory in 1942, a team under Charles M. Cooper developed a lanthanum fluoride process which was chosen for the pilot separation plant.

[224] The F-1 (Super) Group calculated that burning 1 cubic meter (35 cu ft) of liquid deuterium would release the energy of 10 megatonnes of TNT (42 PJ), enough to devastate 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2).

[232][233] Groves did not relish the prospect of explaining to a Senate committee the loss of a billion dollars worth of plutonium, so a cylindrical containment vessel codenamed "Jumbo" was constructed to recover the active material in the event of a failure.

This proved a daunting task given the amount of knowledge and speculation about nuclear fission that existed prior to the Manhattan Project, the huge numbers of people involved, and the scale of the facilities.

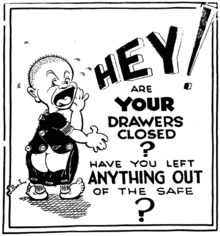

[257] Because of its relative success at keeping the story out of newspapers, Byron Price, head of the Office of Censorship, ultimately designated the Manhattan Project "the best-kept secret of the war".

[259] In 1945 Life estimated that before the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings "probably no more than a few dozen men in the entire country knew the full meaning of the Manhattan Project, and perhaps only a thousand others even were aware that work on atoms was involved."

Warned that disclosing the project's secrets was punishable by 10 years in prison or a fine of US$10,000 (equivalent to $169,000 in 2023), they monitored "dials and switches while behind thick concrete walls mysterious reactions took place" without knowing the purpose of their jobs.

William L. Laurence of The New York Times, who wrote an article on atomic fission in The Saturday Evening Post of 7 September 1940, later learned that government officials asked librarians nationwide in 1943 to withdraw the issue.

Lieutenant Colonel Boris T. Pash, the head of the Counter Intelligence Branch of the Western Defense Command, investigated suspected Soviet espionage at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley.

[289] In April 1945, Pash, in command of a composite force known as T-Force, conducted Operation Harborage, a sweep behind enemy lines of Hechingen, Bisingen, and Haigerloch—the heart of the German nuclear effort.

[290][291] Alsos teams rounded up German scientists including Kurt Diebner, Otto Hahn, Walther Gerlach, Werner Heisenberg, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker.

A party equipped with portable Geiger counters arrived in Hiroshima on 8 September headed by Farrell and Warren, with Japanese Rear Admiral Masao Tsuzuki, who acted as a translator.

As plans were made to turn the work over to the Army Corps of Engineers, Bush wrote to Roosevelt in late 1942 that "it would be ruinous to the essential secrecy to have to defend before an appropriations committee any request for funds for this project."

Issues of this kind resulted in Hanford becoming "one of the most contaminated nuclear waste sites in North America", and the subject of significant cleanup efforts after it was deactivated in the late Cold War.