Maritime republics

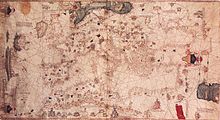

Uniformly scattered across the Italian peninsula, the maritime republics were important not only for the history of navigation and commerce: in addition to precious goods otherwise unobtainable in Europe, new artistic ideas and news concerning distant countries also spread.

From the 10th century, they built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, giving them an essential role in reestablishing contacts between Europe, Asia, and Africa, which had been interrupted during the early Middle Ages.

In Sismondi's text, the maritime republics were seen as cities dedicated above all to fighting each other over issues related to their commercial expansion, unlike the medieval communes, which instead fought together against the Empire courageously defending their freedom.

In 1895, the sailor Augusto Vittorio Vecchi, founder of the Italian Naval League and better known as a writer under the pseudonym Jack la Bolina, wrote General History of the Navy, which was widely circulated and described the military exploits of the maritime cities in chronological order of origin and decay, from Amalfi to Pisa, Genoa and Ancona to Venice.

As many as six of these cities — Amalfi, Venice, Gaeta, Genoa, Ancona, and Ragusa — began their own history of autonomy and trade after being almost destroyed by terrible looting, or were founded by refugees from devastated lands.

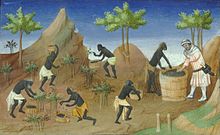

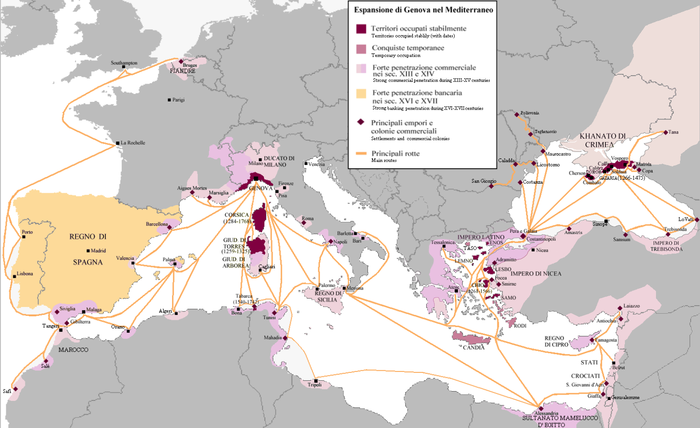

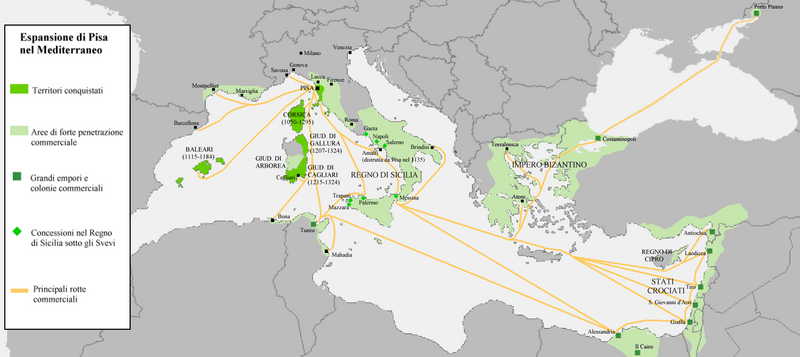

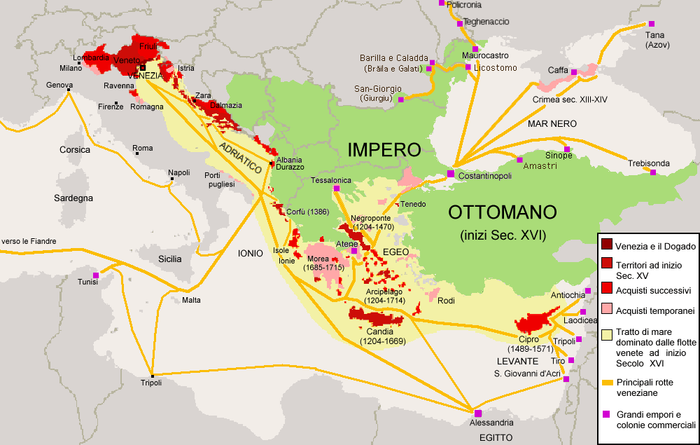

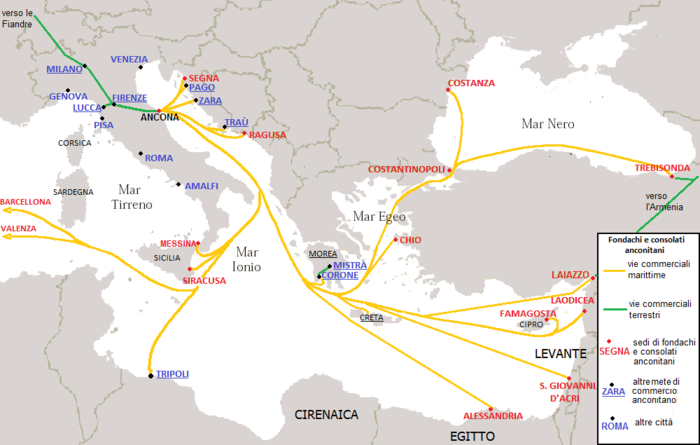

The traffic of these cities reached Africa and Asia, effectively inserting itself between the Byzantine and Islamic maritime powers, with which a complex relationship of competition and collaboration was established for the control of the Mediterranean routes.

Amalfi, Genoa, Venice, Pisa, Ancona and Ragusa were already engaged in trade with the Levant, but with the Crusades thousands of inhabitants of the seaside cities poured into the East, creating warehouses, colonies and commercial establishments.

They exercised great political influence at the local level: Italian merchants set up trade associations in their business centers with the aim of obtaining jurisdictional, fiscal and customs privileges from foreign governments.

The maritime republics reestablished contacts between Europe, Asia and Africa, which were almost interrupted after the fall of the Western Roman Empire; their history is intertwined both with the launch of European expansion towards the East and with the origins of modern capitalism as a mercantile and financial system.

Among the most important products were: The maritime republics' great prosperity deriving from trade had a significant impact on the history of art, to the point that five of them (Amalfi, Genoa, Venice, Pisa and Ragusa) are today included in UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites.

At the dawn of AD 1000, Amalfi was the most prosperous city of Longobardia, and in terms of population (probably 80,000 inhabitants) and prosperity, the only one able to compete with the great Arab metropolises: it minted its own gold coin, the tarì, which was current in all the main Mediterranean ports; the Amalfian Laws, a code of maritime law which remained in force throughout the Middle Ages, date back to that time; in Jerusalem, the noble merchant Mauro Pantaleone built the hospital from which the Knights Hospitaller would originate.

Despite the tenacious tradition that originated, a correct reading of Biondo's passage reveals that Flavio Gioia never existed, and that the glory of the Amalfi people was not that of inventing the compass (actually imported from China), but of having been the first to spread its use in Europe.

In the mid-10th century, entering the dispute between Berengar II and Otto the Great, it obtained de facto independence in 958, which was then made official in 1096 with the creation of the Compagna Communis, a union of merchants and feudal lords of the area.

The 14th century marked a serious economic, political and social crisis for Genoa, which, weakened by internal strife, lost Sardinia to the Aragonese, was defeated by Venice at Alghero (1353) and Chioggia (1379) and subjected several times to France and to the Duchy of Milan.

The republic was weakened by the state's own arrangement, which, based on private agreements between the main families, led to incredibly short and unstable governments and very frequent factional strife.

In this historical period, Pisa intensified its trade in the Mediterranean Sea, allied itself with the Kingdom of Sicily's nascent power, and clashed several times with the Saracen ships, defeating them in Reggio Calabria (1005), in Bona (1034), in Palermo (1064), and in Mahdia (1087).

The life of Fibonacci, a mathematician from Pisa, well expresses the profitable relationship between commerce, navigation and culture typical of the maritime republics; he reworked and disseminated Arab scientific knowledge in Europe, including ten-digit numbering, and the use of zero.

Around the year 1000, Venice began its expansion in the Adriatic Sea, defeating the pirates who occupied the coasts of Istria and Dalmatia and placing those regions and their principal townships under Venetian dominion.

Artistically, Venice had European resonance for centuries: in the Middle Ages by fusing Romanesque, Gothic and Byzantine styles in its architecture; in the Renaissance with the painters Titian, Giorgione, Tintoretto, Bellini and Lotto; in the Baroque period with the composers Antonio Vivaldi, Giuseppe Tartini and Tomaso Albinoni; in the eighteenth century with vedutisti Giambattista Tiepolo and Canaletto, playwright Carlo Goldoni, sculptor Antonio Canova, and writer and adventurer Giacomo Casanova.

In the defense of its freedom, Ancona emerged victorious several times, such as in the siege of 1173, in which Germanic imperial troops surrounded the city from the sea while Venetian ships occupied the port.

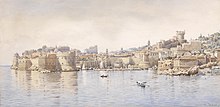

According to the De Administrando Imperio of the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos, Ragusa (now called Dubrovnik) was founded, probably in the 7th century, by the inhabitants of the Roman city of Epidaurum (modern Cavtat) after its destruction by the Avars and Slavs c. 615.

In the face of Hungary's defeat in the Battle of Mohács to the Ottoman Empire in 1526, Ragusa passed under the formal supremacy of the sultan, obliging itself to pay him a symbolic annual tribute, a move which allowed it to safeguard its independence.

By participating in the Crusades, Noli obtained numerous privileges from the Christian sovereigns of Antioch and Jerusalem and above all enormous wealth, with which it was able to gradually buy the various marquis rights from the Marquises of the Carretto House, on whom it depended.

Just ten years after its founding, the consuls of the newborn municipality decided to ally themselves with the nearby and much more powerful Republic of Genoa: in 1202 Noli became its protectorate, a condition that would last for its entire existence.

A strongly Guelph city, it adhered to the Lombard League against Frederick II and was rewarded for this by Pope Gregory IX with the establishment of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Savona-Noli in 1239 and the donation of the island of Bergeggi.

Commercial isolation was added to continuous wars with the neighboring towns of Savona and Finale Ligure, which condemned Noli to a long decline destined to last until the end of independence, which took place in 1797 with the annexation to the Ligurian Republic.

Nonetheless, the Ottoman Empire later made many Genoese and Venetian colonies capitulate and forced the two republics to seek a new destiny: Genoa found it in nascent international finance, and Venice in terrestrial expansion.

To remedy this, it made an alliance with Lucca in the mid-1160s: in exchange for a land attack against Pisa in combination with a naval one, the Genoese would build the Motrone Tower for the Luccans along the via Regia, in the area where Viareggio now stands.

In 1241, Pope Gregory IX called a council in Rome to confirm the excommunication of Frederick II; Genoa, then in the hands of the Guelphs, offered to escort the French, Spanish and Lombard prelates to defend them from the Ghibellines, with the help of Venice and the papacy.

That war ended in favour of Roger II, who gained recognition of his rights over the territories of South Italy, but it was a severe blow for Amalfi, which lost both its fleet and its political autonomy.