Mathematics and art

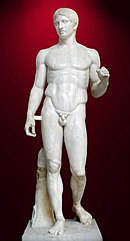

Artists have used mathematics since the 4th century BC when the Greek sculptor Polykleitos wrote his Canon, prescribing proportions conjectured to have been based on the ratio 1:√2 for the ideal male nude.

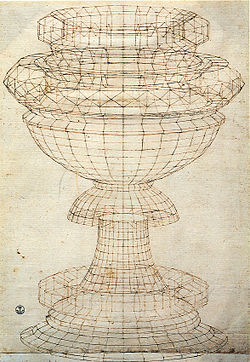

In the Italian Renaissance, Luca Pacioli wrote the influential treatise De divina proportione (1509), illustrated with woodcuts by Leonardo da Vinci, on the use of the golden ratio in art.

In modern times, the graphic artist M. C. Escher made intensive use of tessellation and hyperbolic geometry, with the help of the mathematician H. S. M. Coxeter, while the De Stijl movement led by Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian explicitly embraced geometrical forms.

In Islamic art, symmetries are evident in forms as varied as Persian girih and Moroccan zellige tilework, Mughal jali pierced stone screens, and widespread muqarnas vaulting.

Other relationships include the algorithmic analysis of artworks by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, the finding that traditional batiks from different regions of Java have distinct fractal dimensions, and stimuli to mathematics research, especially Filippo Brunelleschi's theory of perspective, which eventually led to Girard Desargues's projective geometry.

Second, philosophers and artists alike were convinced that mathematics was the true essence of the physical world and that the entire universe, including the arts, could be explained in geometric terms.

In 1415, the Italian architect Filippo Brunelleschi and his friend Leon Battista Alberti demonstrated the geometrical method of applying perspective in Florence, using similar triangles as formulated by Euclid, to find the apparent height of distant objects.

[21] In De Prospectiva Pingendi, Piero transforms his empirical observations of the way aspects of a figure change with point of view into mathematical proofs.

[51] The historian of architecture Frederik Macody Lund argued in 1919 that the Cathedral of Chartres (12th century), Notre-Dame of Laon (1157–1205) and Notre Dame de Paris (1160) are designed according to the golden ratio,[52] drawing regulator lines to make his case.

[64] Symmetries are prominent in textile arts including quilting,[61] knitting,[65] cross-stitch, crochet,[66] embroidery[67][68] and weaving,[69] where they may be purely decorative or may be marks of status.

[71] Items of embroidery and lace work such as tablecloths and table mats, made using bobbins or by tatting, can have a wide variety of reflectional and rotational symmetries which are being explored mathematically.

They are found, for instance, in a marble mosaic featuring the small stellated dodecahedron, attributed to Paolo Uccello, in the floor of the San Marco Basilica in Venice;[12] in Leonardo da Vinci's diagrams of regular polyhedra drawn as illustrations for Luca Pacioli's 1509 book The Divine Proportion;[12] as a glass rhombicuboctahedron in Jacopo de Barbari's portrait of Pacioli, painted in 1495;[12] in the truncated polyhedron (and various other mathematical objects) in Albrecht Dürer's engraving Melencolia I;[12] and in Salvador Dalí's painting The Last Supper in which Christ and his disciples are pictured inside a giant dodecahedron.

[75] Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was a German Renaissance printmaker who made important contributions to polyhedral literature in his 1525 book, Underweysung der Messung (Education on Measurement), meant to teach the subjects of linear perspective, geometry in architecture, Platonic solids, and regular polygons.

[1] These two objects, and the engraving as a whole, have been the subject of more modern interpretation than the contents of almost any other print,[1][79][80] including a two-volume book by Peter-Klaus Schuster,[81] and an influential discussion in Erwin Panofsky's monograph of Dürer.

The mathematician Thomas Banchoff states that Dalí was trying to go beyond the three-dimensional world, while the poet and art critic Kelly Grovier says that "The painting seems to have cracked the link between the spirituality of Christ's salvation and the materiality of geometric and physical forces.

[87] The astronomer Galileo Galilei in his Il Saggiatore wrote that "[The universe] is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures.

[95] Among the connections to the visual arts, mathematics can provide tools for artists, such as the rules of linear perspective as described by Brook Taylor and Johann Lambert, or the methods of descriptive geometry, now applied in software modelling of solids, dating back to Albrecht Dürer and Gaspard Monge.

[95][97] The use of perspective began, despite some embryonic usages in the architecture of Ancient Greece, with Italian painters such as Giotto in the 13th century; rules such as the vanishing point were first formulated by Brunelleschi in about 1413,[6] his theory influencing Leonardo and Dürer.

Isaac Newton's work on the optical spectrum influenced Goethe's Theory of Colours and in turn artists such as Philipp Otto Runge, J. M. W. Turner,[98] the Pre-Raphaelites and Wassily Kandinsky.

[105][107] More recently, Hamid Naderi Yeganeh has created shapes suggestive of real world objects such as fish and birds, using formulae that are successively varied to draw families of curves or angled lines.

[127] The art reporter Jonathan Keats, writing in ForbesLife, argues that Man Ray photographed "the elliptic paraboloids and conic points in the same sensual light as his pictures of Kiki de Montparnasse", and "ingeniously repurposes the cool calculations of mathematics to reveal the topology of desire".

"[130] The artists Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian founded the De Stijl movement, which they wanted to "establish a visual vocabulary comprised of elementary geometrical forms comprehensible by all and adaptable to any discipline".

[d][153] The American weaver Ada Dietz wrote a 1949 monograph Algebraic Expressions in Handwoven Textiles, defining weaving patterns based on the expansion of multivariate polynomials.

[167] Magritte made use of spheres and cuboids to distort reality in a different way, painting them alongside an assortment of houses in his 1931 Mental Arithmetic as if they were children's building blocks, but house-sized.

[168] The Guardian observed that the "eerie toytown image" prophesied Modernism's usurpation of "cosy traditional forms", but also plays with the human tendency to seek patterns in nature.

[170] The image's central void has also attracted the interest of mathematicians Bart de Smit and Hendrik Lenstra, who propose that it could contain a Droste effect copy of itself, rotated and shrunk; this would be a further illustration of recursion beyond that noted by Hofstadter.

Such techniques can uncover images in layers of paint later covered over by an artist; help art historians to visualize an artwork before it cracked or faded; help to tell a copy from an original, or distinguish the brushstroke style of a master from those of his apprentices.

[184] The Japanese paper-folding art of origami has been reworked mathematically by Tomoko Fusé using modules, congruent pieces of paper such as squares, and making them into polyhedra or tilings.

[189] Optical illusions such as the Fraser spiral strikingly demonstrate limitations in human visual perception, creating what the art historian Ernst Gombrich called a "baffling trick."

[195] In 1596, the mathematical astronomer Johannes Kepler modelled the universe as a set of nested Platonic solids, determining the relative sizes of the orbits of the planets.