History of Lithuania

Some of these merged into Lithuanians and Latvians (Samogitians, Selonians, Curonians, Semigallians), while others no longer existed after they were conquered and assimilated by the State of the Teutonic Order (Old Prussians, Yotvingians, Sambians, Skalvians, and Galindians).

[11] The area was remote and unattractive to outsiders, including traders, which accounts for its separate linguistic, cultural and religious identity and delayed integration into general European patterns and trends.

[19] From the early 13th century, two German crusading military orders, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Teutonic Knights, became established at the mouth of the Daugava River and in Chełmno Land respectively.

The Ruthenian duke Daniel of Galicia sensed an occasion to recover Black Ruthenia and in 1249–1250 organized a powerful anti-Mindaugas (and "anti-pagan") coalition that included Mindaugas' rivals, Yotvingians, Samogitians and the Livonian Teutonic Knights.

[26] In 1260, the Samogitians, victorious over the Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Durbe, agreed to submit themselves to Mindaugas' rule on the condition that he abandons the Christian religion; the king complied by terminating the emergent conversion of his country, renewed anti-Teutonic warfare (in the struggle for Samogitia)[30] and expanded further his Ruthenian holdings.

[7][36] The reign of Grand Duke Gediminas constituted the first period in Lithuanian history in which the country was recognized as a great power, mainly due to the extent of its territorial expansion into Ruthenia.

[38][39] In the 14th century, many Lithuanian princes installed to govern the Ruthenia lands accepted Eastern Christianity and assumed Ruthenian custom and names in order to appeal to the culture of their subjects.

Their rivalry weakened the country in the face of the Teutonic expansion and the newly assertive Grand Duchy of Moscow, buoyed by the 1380 victory over the Golden Horde at the Battle of Kulikovo and intent on the unification of all Rus' lands under its rule.

[53] By the time of Jogaila's acceptance of Catholicism at the Union of Krewo in 1385, many institutions in his realm and members of his family had been to a large extent assimilated already into the Orthodox Christianity and became Russified (in part a result of the deliberate policy of the Gediminid ruling house).

[53][54] Catholic influence and contacts, including those derived from German settlers, traders and missionaries from Riga,[55] had been increasing for some time around the northwest region of the empire, known as Lithuania proper.

A Russian deal was also negotiated with Dmitry Donskoy in 1383–1384, but Moscow was too distant to be able to assist with the problems posed by the Teutonic orders and presented a difficulty as a center competing for the loyalty of the Orthodox Lithuanian Ruthenians.

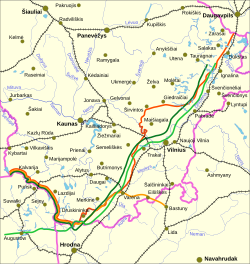

[67][68] During Vytautas' reign, Lithuania reached the peak of its territorial expansion, but his ambitious plans to subjugate all of Ruthenia were thwarted by his disastrous defeat in 1399 at the Battle of the Vorskla River, inflicted by the Golden Horde.

Smolensk was retained, Pskov and Veliki Novgorod ended up as Lithuanian dependencies, and a lasting territorial division between the Grand Duchy and Moscow was agreed in 1408 in the treaty of Ugra, where a great battle failed to materialize.

[75][76] Vytautas practiced religious toleration and his grandiose plans also included attempts to influence the Eastern Orthodox Church, which he wanted to use as a tool to control Moscow and other parts of Ruthenia.

In the Privilege of Vilnius of 1563, Sigismund restored full political rights to the Grand Duchy's Orthodox boyars, which had been restricted up to that time by Vytautas and his successors; all members of the nobility were from then officially equal.

[98] On 29 May 1580 a ceremony was held in the Vilnius Cathedral during which bishop Merkelis Giedraitis presented Stephen Báthory (King of Poland since 1 May 1576) a luxuriously decorated sword and a cap adorned with pearls (both were sanctified by Pope Gregory XIII himself).

[105] The integrating process of the Commonwealth nobility was not regarded as Polonization in the sense of modern nationality, but rather as participation in the Sarmatism cultural-ideological current, erroneously understood to imply also a common (Sarmatian) ancestry of all members of the noble class.

Teodor Narbutt wrote in Polish a voluminous Ancient History of the Lithuanian Nation (1835–1841), where he likewise expounded and expanded further on the concept of historic Lithuania, whose days of glory had ended with the Union of Lublin in 1569.

Jakób Gieysztor, Konstanty Kalinowski and Antanas Mackevičius wanted to form alliances with the local peasants, who, empowered and given land, would presumably help defeat the Russian Empire, acting in their own self-interest.

The two most prominent figures in the revival movement, Jonas Basanavičius and Vincas Kudirka, both originated from affluent Lithuanian peasantry and attended the Mariampol Gymnasium (secondary school) in the Suwałki Governorate.

In 1883, Basanavičius began working on a Lithuanian language review, which assumed the form of a newspaper named Aušra (The Dawn), published in Ragnit, Prussia, Germany (now Neman, Russia).

)[167][168] Lithuania took advantage of the Ruhr Crisis in western Europe and captured the Klaipėda Region, a territory detached from East Prussia by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and placed under a French administration sponsored by the League of Nations.

As tensions were rising in Europe following the annexation of the Federal State of Austria by Nazi Germany (the Anschluss), Poland presented the 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania in March of that year.

[180] However, soon Lithuanians became disillusioned with harsh German policies of collecting large war provisions, gathering people for forced labor in Germany, conscripting men into the Wehrmacht, and the lack of true autonomy.

Adolfas Ramanauskas (code name 'Vanagas', translated to English: the hawk), the last official commander of the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters, was arrested in October 1956 and executed in November 1957.

The country remained largely isolated from the non-Soviet world because of travel restrictions, the persecution of the Catholic Church continued and the nominally egalitarian society was extensively corrupted by the practice of connections and privileges for those who served the system.

On 23 August 1989, 50 years after the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians joined hands in a human chain that stretched 600 kilometres from Tallinn to Vilnius in order to draw the world's attention to the fate of the Baltic nations.

[29] As in many countries of the former Soviet Union, the popularity of the independence movement (Sąjūdis in the case of Lithuania) diminished due to worsening economic situation (rising unemployment, inflation, etc.).

The privatization started with small organizations, and large enterprises (such as telecommunication companies or airlines) were sold several years later for hard currency in a bid to attract foreign investors.

[29] Especially since Lithuania's admission into the European Union, large numbers of Lithuanians (up to 20% of the population) have moved abroad in search of better economic opportunities to create a significant demographic problem for the small country.