Molecular orbital

In chemistry, a molecular orbital (/ɒrbədl/) is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule.

This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of finding an electron in any specific region.

When multiple atoms combine chemically into a molecule by forming a valence chemical bond, the electrons' locations are determined by the molecule as a whole, so the atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals.

Mathematically, molecular orbitals are an approximate solution to the Schrödinger equation for the electrons in the field of the molecule's atomic nuclei.

Molecular orbitals are approximate solutions to the Schrödinger equation for the electrons in the electric field of the molecule's atomic nuclei.

Most commonly a MO is represented as a linear combination of atomic orbitals (the LCAO-MO method), especially in qualitative or very approximate usage.

They are invaluable in providing a simple model of bonding in molecules, understood through molecular orbital theory.

In the case of two electrons occupying the same orbital, the Pauli principle demands that they have opposite spin.

Necessarily this is an approximation, and highly accurate descriptions of the molecular electronic wave function do not have orbitals (see configuration interaction).

[4] The symmetry properties of molecular orbitals means that delocalization is an inherent feature of molecular orbital theory and makes it fundamentally different from (and complementary to) valence bond theory, in which bonds are viewed as localized electron pairs, with allowance for resonance to account for delocalization.

The advantage of this approach is that the orbitals will correspond more closely to the "bonds" of a molecule as depicted by a Lewis structure.

[12] His ground-breaking paper showed how to derive the electronic structure of the fluorine and oxygen molecules from quantum principles.

This qualitative approach to molecular orbital theory is part of the start of modern quantum chemistry.

These coefficients can be positive or negative, depending on the energies and symmetries of the individual atomic orbitals.

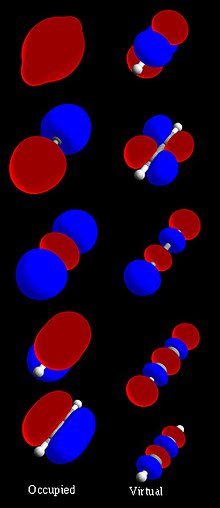

The number of nodal planes containing the internuclear axis between the atoms concerned is zero for σ MOs, one for π, two for δ, three for φ and four for γ.

An MO will have π symmetry if the orbital is asymmetric with respect to rotation about the internuclear axis.

For a bonding MO with π-symmetry the orbital is πu because inversion through the center of symmetry for would produce a sign change (the two p atomic orbitals are in phase with each other but the two lobes have opposite signs), while an antibonding MO with π-symmetry is πg because inversion through the center of symmetry for would not produce a sign change (the two p orbitals are antisymmetric by phase).

[14] The qualitative approach of MO analysis uses a molecular orbital diagram to visualize bonding interactions in a molecule.

Some properties: The general procedure for constructing a molecular orbital diagram for a reasonably simple molecule can be summarized as follows: 1.

Confirm, correct, and revise this qualitative order by carrying out a molecular orbital calculation by using commercial software.

[citation needed] Homonuclear diatomic MOs contain equal contributions from each atomic orbital in the basis set.

[14] As a simple MO example, consider the electrons in a hydrogen molecule, H2 (see molecular orbital diagram), with the two atoms labelled H' and H".

Because the H2 molecule has two electrons, they can both go in the bonding orbital, making the system lower in energy (hence more stable) than two free hydrogen atoms.

The symmetric combination—the bonding orbital—is lower in energy than the basis orbitals, and the antisymmetric combination—the antibonding orbital—is higher.

HeH would have a slight energy advantage, but not as much as H2 + 2 He, so the molecule is very unstable and exists only briefly before decomposing into hydrogen and helium.

Except for short-lived Van der Waals complexes, there are very few noble gas compounds known.

[citation needed] While MOs for homonuclear diatomic molecules contain equal contributions from each interacting atomic orbital, MOs for heteronuclear diatomics contain different atomic orbital contributions.

Since HF is a non-centrosymmetric molecule, the symmetry labels g and u do not apply to its molecular orbitals.

One usually solves this problem by expanding the molecular orbitals as linear combinations of Gaussian functions centered on the atomic nuclei (see linear combination of atomic orbitals and basis set (chemistry)).

There are a number of programs in which quantum chemical calculations of MOs can be performed, including Spartan.