Skeletal muscle

The myonuclei are quite uniformly arranged along the fiber with each nucleus having its own myonuclear domain where it is responsible for supporting the volume of cytoplasm in that particular section of the myofiber.

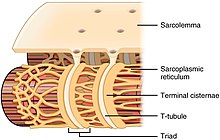

However, fast twitch fibers also demonstrate a higher capability for electrochemical transmission of action potentials and a rapid level of calcium release and uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

[55] In addition to having a genetic basis, the composition of muscle fiber types is flexible and can vary with a number of different environmental factors.

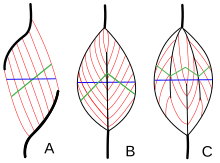

[57] Skeletal muscle exhibits a distinctive banding pattern when viewed under the microscope due to the arrangement of two contractile proteins myosin, and actin – that are two of the myofilaments in the myofibrils.

During embryonic development in the process of somitogenesis the paraxial mesoderm is divided along the embryo's length to form somites, corresponding to the segmentation of the body most obviously seen in the vertebral column.

Myoblast migration is preceded by the formation of connective tissue frameworks, usually formed from the somatic lateral plate mesoderm.

[3] Following contraction, skeletal muscle functions as an endocrine organ by secreting myokines – a wide range of cytokines and other peptides that act as signalling molecules.

Calcium-bound troponin undergoes a conformational change that leads to the movement of tropomyosin, subsequently exposing the myosin-binding sites on actin.

As the ryanodine receptors open, Ca2+ is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the local junctional space and diffuses into the bulk cytoplasm to cause a calcium spark.

The Ca2+ released into the cytosol binds to Troponin C by the actin filaments, to allow crossbridge cycling, producing force and, in some situations, motion.

In this case, the signal from the afferent fiber does not reach the brain, but produces the reflexive movement by direct connections with the efferent nerves in the spine.

Commands are routed through the basal ganglia and are modified by input from the cerebellum before being relayed through the pyramidal tract to the spinal cord and from there to the motor end plate at the muscles.

The cerebellum and red nucleus in particular continuously sample position against movement and make minor corrections to assure smooth motion.

Cardiac muscle on the other hand, can readily consume any of the three macronutrients (protein, glucose and fat) aerobically without a 'warm up' period and always extracts the maximum ATP yield from any molecule involved.

The heart, liver and red blood cells will also consume lactic acid produced and excreted by skeletal muscles during exercise.

The mechanical energy output of a cyclic contraction can depend upon many factors, including activation timing, muscle strain trajectory, and rates of force rise & decay.

[71] Some invertebrate muscles, such as in crab claws, have much longer sarcomeres than vertebrates, resulting in many more sites for actin and myosin to bind and thus much greater force per square centimeter at the cost of much slower speed.

The maximum holding time for a contracted muscle depends on its supply of energy and is stated by Rohmert's law to exponentially decay from the beginning of exertion.

Part of the training process is learning to relax the antagonist muscles to increase the force input of the chest and anterior shoulder.

A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (PPARδ)-mediated transcriptional pathway is involved in the regulation of the skeletal muscle fiber phenotype.

Thus—through functional genomics—calcineurin, calmodulin-dependent kinase, PGC-1α, and activated PPARδ form the basis of a signaling network that controls skeletal muscle fiber-type transformation and metabolic profiles that protect against insulin resistance and obesity.

These include a switch from fat-based to carbohydrate-based fuels, a redistribution of blood flow from nonworking to exercising muscles, and the removal of several of the by-products of anaerobic metabolism, such as carbon dioxide and lactic acid.

Moreover, the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF1A) has been identified as a master regulator for the expression of genes involved in essential hypoxic responses that maintain ATP levels in cells.

Physical exercise is often recommended as a means of improving motor skills, fitness, muscle and bone strength, and joint function.

Aerobic exercise (e.g. marathons) involves activities of low intensity but long duration, during which the muscles used are below their maximal contraction strength.

[80] During anaerobic exercise, type II fibers consume little oxygen, protein and fat, produce large amounts of lactic acid and are fatigable.

[5][84] Some inflammatory myopathies include polymyositis and inclusion body myositis Neuromuscular diseases affect the muscles and their nervous control.

Diagnostic procedures that may reveal muscular disorders include testing creatine kinase levels in the blood and electromyography (measuring electrical activity in muscles).

[103] Of these individuals, 1,605 participants (19.4%) were considered to have a low skeletal muscle mass at baseline, with less than 7.30 kg/m2 for males, and less than 5.42 kg/m2 for females (levels defined as sarcopenia in Canada).

[102] The main pathways found to be affected by secreted exercise-regulated proteins were related to cardiac, cognitive, kidney and platelet functions.