Nuclear organization

At a larger scale, chromosomes are organised into two compartments labelled A ("active") and B ("inactive"), which are further subdivided into sub-compartments.

However, in order for the cell to function, proteins must be able to access the sequence information contained within the DNA, in spite of its tightly-packed nature.

[7] Additionally, high-throughput sequencing technologies such as Chromosome Conformation Capture-based methods can measure how often DNA regions are in close proximity.

[8] At the same time, progress in genome-editing techniques (such as CRISPR/Cas9, ZFNs, and TALENs) have made it easier to test the organizational function of specific DNA regions and proteins.

[9] There is also growing interest in the rheological properties of the interchromosomal space, studied by the means of Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy and its variants.

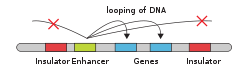

[10][11] Architectural proteins regulate chromatin structure by establishing physical interactions between DNA elements.

[13][14] In mammals, key architectural proteins include: The organization of DNA within the nucleus begins with the 10 nm fiber, a "beads-on-a-string" structure[24] made of nucleosomes connected by 20-60bp linkers.

While 30 nm fiber is often visible in vitro under high salt concentration,[25] its existence in vivo has been questioned in many recent studies.

cLADs are A-T rich heterochromatin regions that remain on lamina and are seen across many types of cells and species.

On the other hand, fLADs have varying lamina interactions and contain genes that are either activated or repressed between individual cells indicating cell-type specificity.

[34] The boundaries of LADs, like self-interacting domains, are enriched in transcriptional elements and architectural protein binding sites.

In fact, DNA analysis of these two types of domains have shown that many sequences overlap, indicating that certain regions may switch between lamina-binding and nucleolus-binding.

[37] A compartments tend to be gene-rich, have high GC-content, contain histone markers for active transcription, and usually displace the interior of the nucleus.

B compartments, on the other hand, tend to be gene-poor, compact, contain histone markers for gene silencing, and lie on the nuclear periphery.

[37] In addition, higher resolution Hi-C coupled with machine learning methods has revealed that A/B compartments can be refined into subcompartments.

[39][40] The fact that compartments self-interact is consistent with the idea that the nucleus localizes proteins and other factors such as long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) in regions suited for their individual roles.

The final characteristic is that the position of individual chromosomes during each cell cycle stays relatively the same until the start of mitosis.