Odds ratio

Suppose a radiation leak in a village of 1,000 people increased the incidence of a rare disease.

It is standard in the medical literature to calculate the odds ratio and then use the rare-disease assumption (which is usually reasonable) to claim that the relative risk is approximately equal to it.

This not only allows for the use of case-control studies, but makes controlling for confounding variables such as weight or age using regression analysis easier and has the desirable properties discussed in other sections of this article of invariance and insensitivity to the type of sampling.

The odds ratio can also be defined in terms of the joint probability distribution of two binary random variables.

The joint distribution of binary random variables X and Y can be written where p11, p10, p01 and p00 are non-negative "cell probabilities" that sum to one.

If we had calculated the odds ratio based on the conditional probabilities given Y, we would have obtained the same result Other measures of effect size for binary data such as the relative risk do not have this symmetry property.

The logarithm of the odds ratio, the difference of the logits of the probabilities, tempers this effect, and also makes the measure symmetric with respect to the ordering of groups.

If we use the joint probability notation defined above, the population log odds ratio is If we observe data in the form of a contingency table then the probabilities in the joint distribution can be estimated as where ︿pij = nij / n, with n = n11 + n10 + n01 + n00 being the sum of all four cell counts.

An alternative approach to inference for odds ratios looks at the distribution of the data conditionally on the marginal frequencies of X and Y.

An advantage of this approach is that the sampling distribution of the odds ratio can be expressed exactly.

Note however that the standard error of the log odds ratio does depend on the value of f.[citation needed] This fact is exploited in two important situations: In both these settings, the odds ratio can be calculated from the selected sample, without biasing the results relative to what would have been obtained for a population sample.

Due to the widespread use of logistic regression, the odds ratio is widely used in many fields of medical and social science research.

The odds ratio is commonly used in survey research, in epidemiology, and to express the results of some clinical trials, such as in case-control studies.

For non-statisticians, the odds ratio is a difficult concept to comprehend, and it gives a more impressive figure for the effect.

[13] This may reflect the simple process of uncomprehending authors choosing the most impressive-looking and publishable figure.

For that reason, there is not a consensus within the fields of epidemiology or biostatistics that relative risks or odds-ratios should be preferred when both can be validly used, such as in clinical trials and cohort studies [15] The odds ratio has another unique property of being directly mathematically invertible whether analyzing the OR as either disease survival or disease onset incidence – where the OR for survival is direct reciprocal of 1/OR for risk.

In contrast, the relative risk does not possess this mathematical invertible property when studying disease survival vs. onset incidence.

The danger to clinical interpretation for the OR comes when the adverse event rate is not rare, thereby exaggerating differences when the OR rare-disease assumption is not met.

On the other hand, when the disease is rare, using a RR for survival (e.g. the RR=0.9796 from above example) can clinically hide and conceal an important doubling of adverse risk associated with a drug or exposure.

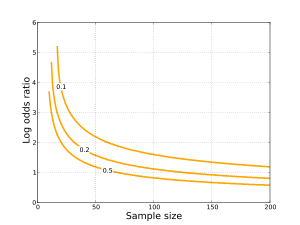

When one or more of the cells in the contingency table can have a small value, the sample odds ratio can be biased and exhibit high variance.

[citation needed] The following four contingency tables contain observed cell counts, along with the corresponding sample odds ratio (OR) and sample log odds ratio (LOR): The following joint probability distributions contain the population cell probabilities, along with the corresponding population odds ratio (OR) and population log odds ratio (LOR): There are various other summary statistics for contingency tables that measure association between two events, such as Yule's Y, Yule's Q; these two are normalized so they are 0 for independent events, 1 for perfectly correlated, −1 for perfectly negatively correlated.

Edwards (1963) studied these and argued that these measures of association must be functions of the odds ratio, which he referred to as the cross-ratio.

[citation needed] A case-control study involves selecting representative samples of cases and controls who do, and do not, have some disease, respectively.

This permits the estimation of the odds ratio for disease in exposed vs. unexposed people as noted above.

The exposure of matched case and control pairs is correlated due to the similar values of their shared confounding variables.

by showing that it is a special case of the Mantel-Haenszel estimate of the intra-strata odds ratio for stratified 2x2 tables.

[17] All study subjects were involved in an automobile crash requiring hospital attendance.

We would expect that a person's cell phone use at the time of the crash would be correlated with his/her use one week earlier.

This allows us to reject the hypothesis that cell phone use has no effect on the risk of automobile crashes (

(McEvoy et al.[21] analyzed their data using conditional logistic regression and obtained almost identical results to those given here.