Asturian language

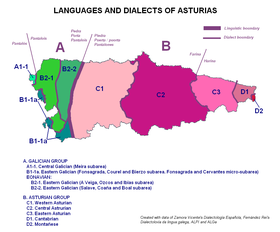

Asturian (/æˈstʊəriən/; asturianu [astuˈɾjanʊ])[4][5] is a West Iberian Romance language spoken in the Principality of Asturias, Spain.

[10] Asturian is the historical language of Asturias, portions of the Spanish provinces of León and Zamora and the area surrounding Miranda do Douro in northeastern Portugal.

During the 12th, 13th and part of the 14th centuries Astur-Leonese was used in the kingdom's official documents, with many examples of agreements, donations, wills and commercial contracts from that period onwards.

Castilian Spanish arrived in the area during the 14th century, when the central administration sent emissaries and functionaries to political and ecclesiastical offices.

The ambiguity of the Statute of Autonomy, which recognises the existence of Asturian but does not give it the same status as Spanish, leaves the door open to benign neglect.

However, since 1 August 2001 Asturian has been covered under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages' "safeguard and promote" clause.

[19] Although some 10th-century documents have the linguistic features of Asturian, numerous examples (such as writings by notaries, contracts and wills) begin in the 13th century.

Although the Asturian language disappeared from written texts during the sieglos escuros (dark centuries), it survived orally.

The only written mention during this time is from a 1555 work by Hernán Núñez about proverbs and adages: "...in a large copy of rare languages, as Portuguese, Galician, Asturian, Catalan, Valencian, French, Tuscan..."[23] Modern Asturian literature began in 1605 with the clergyman Antón González Reguera and continued until the 18th century (when it produced, according to Ruiz de la Peña in 1981, a literature comparable to that in Asturias in Castilian).

[24] In 1744, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos wrote about the historic and cultural value of Asturian, urging the compilation of a dictionary and a grammar and the creation of a language academy.

Notable writers included Francisco Bernaldo de Quirós Benavides (1675), Xosefa Xovellanos (1745), Xuan González Villar y Fuertes (1746), Xosé Caveda y Nava (1796), Xuan María Acebal (1815), Teodoro Cuesta (1829), Xosé Benigno García González, Marcos del Torniello (1853), Bernardo Acevedo y Huelves (1849), Pin de Pría (1864), Galo Fernández and Fernán Coronas (1884).

El Surdimientu (the Awakening) authors such as Manuel Asur (Cancios y poemes pa un riscar), Xuan Bello (El llibru vieyu), Adolfo Camilo Díaz (Añada pa un güeyu muertu), Pablo Antón Marín Estrada (Les hores), Xandru Fernández (Les ruines), Lourdes Álvarez, Martín López-Vega, Miguel Rojo and Lluis Antón González broke from the Asturian-Leonese tradition of rural themes, moral messages and dialogue-style writing.

Traditional, popular place names of the principality's towns are supported by the law on usage of Asturian, the principality's 2003–07 plan for establishing the language[26] and the work of the Xunta Asesora de Toponimia,[27] which researches and confirms the Asturian names of requesting villages, towns, conceyos and cities (50 of 78 conceyos as of 2012).

The model for the written language, it is characterized by feminine plurals ending in -es, the monophthongization of /ou/ and /ei/ into /o/ and /e/ and the neuter gender[28] in adjectives modifying uncountable nouns (lleche frío, carne tienro).

The dialect is characterized by the debuccalization of word-initial /f/ to [h], written ⟨ḥ⟩ (ḥoguera, ḥacer, ḥigos and ḥornu instead of foguera, facer, figos and fornu; feminine plurals ending in -as (ḥabas, ḥormigas, ḥiyas, except in eastern towns, where -es is kept: ḥabes, ḥormigues, ḥiyes); the shifting of word-final -e to -i (xenti, tardi, ḥuenti); retention of the neuter gender[28] in some areas, with the ending -u instead of -o (agua friu, xenti güenu, ropa tendíu, carne guisáu), and a distinction between direct and indirect objects in first- and second-person singular pronouns (direct me and te v. indirect mi and ti) in some municipalities bordering the Sella: busquéte (a ti) y alcontréte/busquéti les llaves y alcontrétiles, llévame (a mi) la fesoria en carru.

Asturian has triple gender distinction in the adjective, feminine plurals with -es, verb endings with -es, -en, -íes, íen and lacks compound tenses[32] (or periphrasis constructed with "tener").

[33] Verbs agree with their subjects in person (first, second, or third) and number, and are conjugated to indicate mood (indicative, subjunctive, conditional or imperative; some others include "potential" in place of future and conditional),[33] tense (often present or past; different moods allow different tenses), and aspect (perfective or imperfective).

They have no plural, except when they are used metaphorically or concretised and lose this gender: les agües tán fríes (Waters are cold).

[34] As with other Romance languages, most Asturian words come from Latin: ablana, agua, falar, güeyu, home, llibru, muyer, pesllar, pexe, prau, suañar.

Words from this language and the pre–Indo-European languages spoken in the region are known as the prelatinian substratum; examples include bedul, boroña, brincar, bruxa, cándanu, cantu, carrascu, comba, cuetu, güelga, llamuerga, llastra, llócara, matu, peñera, riega, tapín and zucar.

The Germanic peoples in the Iberian Peninsula, especially the Visigoths and the Suevi, added words such as blancu, esquila, estaca, mofu, serón, espetar, gadañu and tosquilar.

Examples include acebache, alfaya, altafarra, bañal, ferre, galbana, mandil, safase, xabalín, zuna and zucre.

Some Castilian forms in Asturian are: Pá nuesu que tas nel cielu, santificáu seya'l to nome.

Amiye'l to reinu, fágase la to voluntá, lo mesmo na tierra que'n cielu.

El nuesu pan cotidianu dánoslu güei ya perdónanos les nueses ofenses, lo mesmo que nós facemos colos que nos faltaron.

According to article six of the University of Oviedo charter, "The Asturian language will be the object of study, teaching and research in the corresponding fields.

[45][46] Free software in the language is available from Debian, Fedora, Firefox, Thunderbird, LibreOffice, VLC, GNOME, Chromium and KDE.