Plant microbiome

[8][1][9][2] The study of the association of plants with microorganisms precedes that of the animal and human microbiomes, notably the roles of microbes in nitrogen and phosphorus uptake.

The most notable examples are plant root-arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) and legume-rhizobial symbioses, both of which greatly influence the ability of roots to uptake various nutrients from the soil.

Some of these microbes cannot survive in the absence of the plant host (obligate symbionts include viruses and some bacteria and fungi), which provides space, oxygen, proteins, and carbohydrates to the microorganisms.

[8][12][1] Recent developments in multiomics and the establishment of large collections of microorganisms have dramatically increased knowledge of the plant microbiome composition and diversity.

The sequencing of marker genes of entire microbial communities, referred to as metagenomics, sheds light on the phylogenetic diversity of the microbiomes of plants.

[13] The focus of plant microbiome studies has been directed at model plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, as well as important economic crop species including barley (Hordeum vulgare), corn (Zea mays), rice (Oryza sativa), soybean (Glycine max), wheat (Triticum aestivum), whereas less attention has been given to fruit crops and tree species.

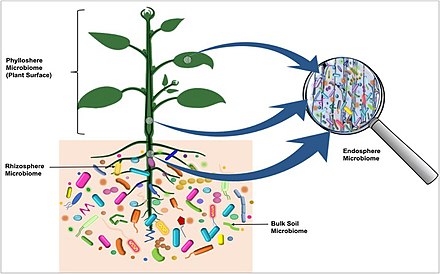

[30] A diverse array of organisms specialize in living in the rhizosphere, including bacteria, fungi, oomycetes, nematodes, algae, protozoa, viruses, and archaea.

[34] Recent studies of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi using sequencing technologies show greater between-species and within-species diversity than previously known.

[35][5] The most frequently studied beneficial rhizosphere organisms are mycorrhizae, rhizobium bacteria, plant-growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), and biocontrol microbes.

It has been projected that one gram of soil could contain more than one million distinct bacterial genomes,[36] and over 50,000 OTUs (operational taxonomic units) have been found within the potato rhizosphere.

[48] The leaf surface, or phyllosphere, harbours a microbiome comprising diverse communities of bacteria, fungi, algae, archaea, and viruses.

[56] There can be up to 107 microbes per square centimetre present on the leaf surfaces of plants, and the bacterial population of the phyllosphere on a global scale is estimated to be 1026 cells.

[49][57][55] However, although the leaf surface is generally considered a discrete microbial habitat,[60][61] there is no consensus on the dominant driver of community assembly across phyllosphere microbiomes.

For example, host-specific bacterial communities have been reported in the phyllosphere of co-occurring plant species, suggesting a dominant role of host selection.

However, the existing evidence does indicate that phyllosphere microbiomes exhibiting host-specific associations are more likely to interact with the host than those primarily recruited from the surrounding environment.

[74][55] Tissue- and species-specific core microbiomes across host populations separated by broad geographical distances have not been widely reported for the phyllosphere using the stringent definition established by Ruinen.

In contrast, non-core phyllosphere microorganisms exhibited significant variation across individual host trees and populations that was strongly driven by environmental and spatial factors.

[55] Plant seeds can serve as natural vectors for vertical transmission of their beneficial endophytes, such as those that confer disease resistance.

A 2021 research paper explained, "It makes sense that their most important symbionts would be vertically transmitted through seed rather than gambling that all of the correct soil-dwelling microbes might be available at the germination site.

[45][86] If the research on oaks turns out to apply to other tree species, it will be understood that the above-soil portions of a plant (the phyllosphere) obtain nearly all of their beneficial fungi from those carried in the seed.

"[82][87] Benefits to the host plant include their ability to assist in the production of antimicrobial compounds, detoxification, nutrient uptake, and growth-promoting activities.

Such partners may contribute to "seed dormancy and germination, environmental adaptation, resistance and tolerance against diseases, and growth promotion.

(2) On the root surface, cyanobacteria exhibit two types of colonization pattern; in the root hair , filaments of Anabaena and Nostoc species form loose colonies, and in the restricted zone on the root surface, specific Nostoc species form cyanobacterial colonies.

(3) Co-inoculation with 2,4-D and Nostoc spp. increases para-nodule formation and nitrogen fixation. A large number of Nostoc spp. isolates colonize the root endosphere and form para-nodules. [ 27 ]

microbes, and root exudates [ 29 ]

on the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana

a) Overview of an A. thaliana root (primary root) with numerous root hairs. b) Biofilm-forming bacteria. c) Fungal or oomycete hyphae surrounding the root surface. d) Primary root densely covered by spores and protists . e, f) Protists , most likely belonging to the Bacillariophyceae class. g) Bacteria and bacterial filaments . h, i) Different bacterial individuals showing great varieties of shapes and morphological features. [ 32 ]

(B) The chart on the right shows how OTUs in phyllosphere and associated soil communities differed in relative abundances. [ 55 ]